- Published by:

- Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

- Date:

- 2 Sep 2025

The Victorian Government is working towards a future where every person is safe, respected and free from violence.

To guide this important work, we have launched Until every Victorian is safe: Third rolling action plan to end family and sexual violence 2025 to 2027 (Until every Victorian is safe).

Until every Victorian is safe supports the implementation of the Victorian Government’s 10-year plan released in 2016, Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s Plan for Change.

Since then, we have transformed the way Victoria prevents and responds to family and sexual violence. This includes implementing all 227 recommendations of the Royal Commission into Family Violence in 2023.

Until every Victorian is safe builds on the first and second rolling action plans under Ending Family Violence: Victoria’s Plan for Change. It also extends on Strong Foundations: Building on Victoria’s work to end family violence, which was published in 2023 to explain our progress so far and what is needed next.

While progress has been made, there is still much work to do. Family violence remains widespread across Victoria. It is fuelled by gender inequality and harmful gender stereotypes, in a society where women are still treated as unequal to men on many levels. It affects people of all ages from all backgrounds including LGBTIQA+ communities.

Until every Victorian is safe outlines 106 actions, which all parts of the Victorian Government must work together to achieve over the next three years.

It includes four focus areas that explain the Victorian Government’s approach:

- Whole of person – understanding that everyone has different needs, making sure that our actions consider people’s unique experiences and needs.

- Whole of family – recognising that families can be both a source of harm and safety, meaning that we need to understand a person’s family context when providing support.

- Whole of community – encouraging people to challenge the attitudes and systems that drive family and sexual violence, including by preventing violence in places where Victorians live, work, study and play.

- Whole of system – refining laws, services, and processes to work together to more effectively prevent and respond to family and sexual violence.

Until every Victorian is safe was informed by extensive stakeholder engagement, reflecting a diverse range of perspectives and priorities. This process involved the expertise of people with lived experience of family and sexual violence, including the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council (VSAC).

VSAC is made up of a collective of diverse people from across Victoria with lived experience of family violence. Members are selected to provide advice to the Victorian Government on policies, programs and laws to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence. Read the VSAC Statement September 2025.

Until every Victorian is safe also aligns with and complements Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families 2018-2028. This is an Aboriginal-led Victorian Agreement that commits Aboriginal communities, Aboriginal services, and government to work together and be accountable for ensuring that Aboriginal people, families and communities are stronger, safer, thriving and living free from family violence.

Ending family violence involves everyone. We all have a role to play – at home, at work and in our communities.

Hear more about our collective approach to action from key leaders and advocates:

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Country

The Victorian Government acknowledges Victorian Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water we depend on. We acknowledge and respect that Aboriginal communities have a rich heritage built on a strong social and cultural foundation that has endured for 60,000 years. We also acknowledge the significant disruptions and ongoing pain caused by colonisation.

We acknowledge the vital leadership role of Aboriginal communities, especially women, in addressing and preventing family and sexual violence. We are dedicated to working with Aboriginal people to eliminate family violence in all communities.

We want to rectify past wrongs and acknowledge the ongoing harm caused by colonisation. To this end, we are committed to self-determination and to supporting Truth and Treaty processes.

Commitment to supporting those affected by family violence

The Victorian Government acknowledges and supports those who have experienced violence, including adults of all ages, children, young people and members of our workforce. The work we do to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence is for them. It is guided by their experience, expertise and advocacy.

We remember and pay respects to those who did not survive and extend our respects to all of those who have lost loved ones to family and sexual violence.

We keep in mind all those who have been, or continue to be, affected by family or sexual violence, and recognise their continued courage and strength.

Family and sexual violence services and support

If you have experienced family violence or sexual assault and need immediate or ongoing assistance, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) to talk to a counsellor from the National Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence hotline.

For confidential support and information, contact Safe Steps’ 24/7 family violence response line on 1800 015 188.

If you have an immediate concern for your safety or that of someone else, please contact the police in your state or territory, or call Triple Zero (000) for emergency help.

In Victoria, The Orange Door provides help for people who are experiencing family violence. It is not an emergency service. You can find your nearest location on The Orange Door’s Support near you web page.

Foreword from the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Family and sexual violence cause enormous hurt and harm in our community.

Family and sexual violence cause enormous hurt and harm in our community.

Historically, the scale and impact of family and sexual violence was largely hidden and ignored. Violence was often downplayed, justified or seen as a ‘private matter’. Victim survivors were too often left to fend for their own safety or find their way to grassroot specialist services.

The Royal Commission into Family Violence in 2016 marked a turning point. We heard from victim survivors and advocates, we witnessed their anguish and learned how violence had upended their lives and sense of safety. We were also humbled by their stories of recovery, healing and advocacy for change.

Victoria has now implemented all of the Commission’s 227 recommendations. We matched our action with investment, providing over $4 billion since the Commission to continue our efforts to end family violence.

Under our 10-year plan, Ending family violence: Victoria’s plan for change, Victoria has transformed how it prevents and responds to family and sexual violence. This is something to be proud of. Together, we have contributed to changes at a scale and pace rarely seen before in Australia. Thousands of people across the state have brought this change to life. People with lived experience and their families, advocates, workers, service providers and government have worked together to make Victoria safer.

But ending family and sexual violence is complex. Gendered drivers are deeply embedded in our society. While people who use violence are ultimately responsible for their choices, we know that violence can be harder to disrupt when people have experienced trauma, struggled with their mental health, substance use or gambling. This all sits alongside an ever-changing backdrop, with technology and social media continually throwing up new challenges that require us to adapt and change.

This rolling action plan reflects our next steps. Some of our actions pioneer new ideas. For example, immersing an entire community in violence prevention initiatives through the Respect Ballarat: A community model to prevent gendered violence.

We will build on what works. Guiding attitudes and behaviours in younger generations through respectful relationships education. Helping parents and carers navigate the complexities of an online world.

We will continue to listen to victim survivors – including children and young people – on how we can effectively protect them from harm. We will work to ensure victim survivors have a safe and stable home they can recover in. We will make sure they have greater access to services that support healing, recovery and justice.

People who use violence will be held accountable and supported to change their behaviour. We will deepen our understanding of perpetrator motivations, behaviours and tactics through research to make sure our interventions align with evidence of what works. Adults who present serious risk will be closely monitored and subject to intensive interventions. This includes through the justice system and strong laws that reflect the varied and often calculating ways violence is used (such as coercive control).

We will use different strategies to support young people who use violence and their families, which are therapeutic and non-stigmatising, but work hard to turn their behaviours around.

We will roll out a new risk assessment framework tailored to the needs of children and young people. The framework will make sure all services consistently and capably respond to and meet the needs of children.

We will look at how we can improve the regulation of alcohol and gambling. We know these factors can worsen the use of violence and the harm it causes.

Our work will strengthen the foundations of our family and sexual violence systems. This includes making sure:

- we are collecting and analysing the right data

- we have enough skilled and supported workers for our programs and services

- technology helps rather than hinders our efforts.

Every action in this plan has been developed with overarching principles that:centre lived experience

- reflect intersectionality and diversity

- uphold Aboriginal self-determination

- recognise our collective accountability to end violence.

We are grateful to the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council and other victim survivors, as well as to all the workforces, services and community groups that help to make Victoria safer.

I also want to thank those who took the time to share their insights and expertise to help shape this plan.

The Victorian Government remains deeply committed to this important work.

Together, we will not stop until every Victorian is safe, thriving and living free from violence.

The Hon. Natalie Hutchins

Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Glossary

In this plan, the words ‘our’ and ‘we’ refer to the Victorian Government.

The term ‘the government’ also refers to the Victorian Government unless stated otherwise.

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Aboriginal | Refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in Victoria. This is consistent with the Aboriginal-led strategy to end family violence, Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families. The terms ‘Koorie’, ‘Koori’ or ‘First Peoples’ are also used occasionally for specific programs and initiatives. |

| Adults who use violence | Used in response to stakeholder feedback, particularly from Aboriginal people, children’s advocates and people who have experienced elder abuse. The term ‘perpetrator’ is used in some sections when talking about specific programs or responses to adult offenders. |

| Consent | Consent is an agreement between participants to take part in sexual activity. Consent must be active, ongoing, and freely given every time. The age of consent is 16, and it cannot be assumed, coerced, or given by someone underage, intoxicated, unconscious, pressured, or misled. Sharing intimate images also requires consent and both people must be over 18. For more information visit: https://www.police.vic.gov.au/consent-laws For support call: |

| Elder abuse | Refers to any act occurring in a relationship with an implication of trust that results in harm to an older person. The abuse may be:

It can also include mistreatment and neglect. Elder abuse is considered a form of family violence when it occurs between family members or people who share a family-like relationship. Elder abuse does not include professional misconduct or consumer scams. |

| Family violence | The use of violence by a current or former intimate partner or family member. This includes people who share a family-like relationship with the person they are harming. For example, it can include:

Family violence is not just physical. It also includes:

|

| Gender-based violence | Violence that is used against someone because of their gender. People of all genders can experience gender-based violence. However, this term is most often used to describe violence against women and girls. This is because most gender-based violence is perpetrated by heterosexual, cisgender men against women, because they are women.[1] Gender-based violence is driven by rigid gender stereotypes, sexism and disrespect.[2] |

| Primary prevention | Primary prevention of family and sexual violence is a long-term agenda to stop violence before it starts. It targets the root causes of violence, which are grounded in gender inequality and harmful social norms. This involves addressing the ‘gendered drivers of violence’. Primary prevention works to change:

Our approach to primary prevention is underpinned by Change the story, Australia’s shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women. |

| Sexual violence or sexual assault | A type of violence where any sexual act is attempted or occurs without consent. Sexual violence can be a form of family violence. It can also be perpetrated outside of a family context. |

| Victim survivor, survivor and person who has experienced violence | Terms used to describe a person who has experienced family or sexual violence, including children and young people. ‘Victim survivor’ includes people who may identify more with the ‘victim’ or the ‘survivor’ term at different points. Some people may also feel they have progressed beyond being a survivor. The Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council guides us on the terms we use. We acknowledge that people harmed by family and sexual violence choose different ways to identify themselves and others. |

| Violence against women | Refers to violence:

The term ‘women’ includes cisgender, trans and gender diverse women and sistergirls. |

| Young people who use violence | Refers to people under 18 years of age who use violence. This term recognises important developmental considerations and the very different service responses that apply to children and young people. It covers both violence against an intimate partner or in a family setting. We often use ‘in the home’ to refer to violence in a family setting. |

[1] Commonwealth of Australia, 2022, National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032.

[2] Our Watch, 2021, Change the story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia (2nd ed.), Melbourne, Australia

[3] Our Watch, 2021, Change the story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia (2nd ed.), Melbourne, Australia

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| CSV | Court Services Victoria |

| DE | Department of Education |

| DFFH | Department of Families, Fairness and Housing |

| DH | Department of Health |

| DJCS | Department of Justice and Community Safety |

| FVIO | Family violence intervention order |

| FVISS | Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme |

| LGBTIQA+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, intersex, queer and questioning, and asexual |

| MARAM | Victoria’s Family violence multi-agency risk assessment and management framework |

| SFVC | Specialist family violence court |

| VicPol | Victoria Police |

| VSAC | Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council |

Building on strong foundations

Ending Family Violence is a 10-year plan that began in 2017. Ending Family Violence sets out the goals we want to achieve. We use rolling action plans to outline the practical steps needed to meet these goals.

Ending Family Violence is a 10-year plan that began in 2017. Ending Family Violence sets out the goals we want to achieve. We use rolling action plans to outline the practical steps needed to meet these goals.

Rolling action plans let us create a strong foundation and then build on it based on new knowledge and evidence. We have already released 2 action plans to date.

The first action plan

In the first 3 years of the Ending Family Violence Plan (2017 to 2020), we focused on getting the foundations in place. Some of the highlights of this work are outlined in Table 3.

Key reform achievements

Since 2021–22

Over 180,000 people have participated in primary prevention programs.

Since 2019–20

14 specialist family violence courts (SFVCs) gazetted by the Victorian Government - final in Wyndham 2025.

Since 2018–19

19 Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (ACCOs) were funded to offer family violence and sexual assault services, including:

- Aboriginal-designed sexual assault services

- healing programs

- responses for people using violence.

Since 2018

The Orange Door has responded to over 590,000 people, 40% were children and young people.

Since 2017–18

Over 45,000 people engaged with DFFH-funded interventions for people who use violence.

Since 2017–18

Over 25,000 children and young people took part in family violence therapeutic interventions.

Since 2017

Over 2,000 Victorian schools took part in the Respectful Relationships program.

Guiding principles

These principles are ongoing commitments that underpin our response to family and sexual violence.

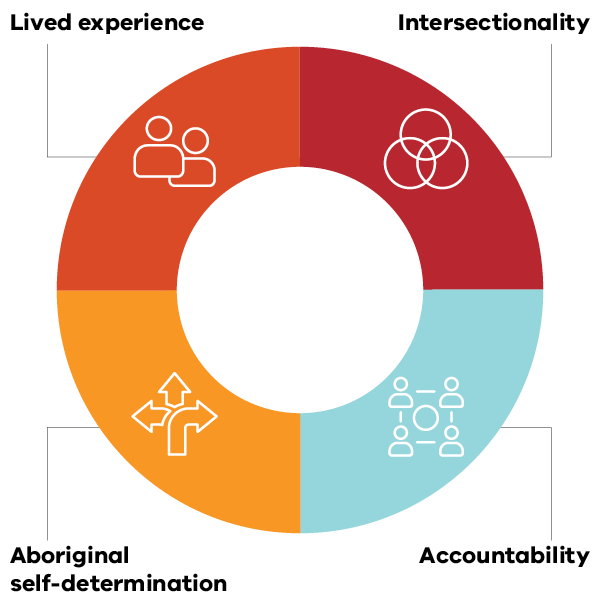

Our work and this plan are guided by a set of 4 core principles:

- lived experience

- intersectionality

- Aboriginal self-determination

- accountability.

These principles are ongoing commitments that underpin our response to family and sexual violence.

Our approach

Innovating, expanding and refining

To create a world with no family or sexual violence, we must have ambition, persistence, and the courage to try new things.

Some of the actions in this plan are bold and innovative. They will challenge us to do things differently. For example, Respect Victoria’s Respect Ballarat, a community model which tasks the entire community with actively preventing gender-based violence.

Other actions push us to keep adapting, expanding and refining the way we work to better meet the needs of people affected by violence. This involves building on some of the transformational changes we have made over the last decade.

A unified roadmap

With this plan, we create a single, unified roadmap for addressing family and sexual violence, and all forms of violence against women.

This plan brings together work of other relevant strategies and plans, including:

- Free from violence: Victoria’s strategy to prevent family violence and all forms of violence against women (Free from Violence)

- Everybody matters: Inclusion and equity statement – sets out our vision for a more inclusive, safe, responsive and accountable family violence system

- Framing the future: Second rolling action plan (under Building from strength: 10-year industry plan for family violence prevention and response) – actions to strengthen and support the family violence workforce.

By bringing together actions from primary prevention, inclusion and workforce plans, we can embed these critical efforts in broader reform. This makes sure they are visible, sustained and coordinated drivers of long-term change. We are strongly committed to these important reforms, which will continue to guide our progress.

This plan also includes initiatives from the Strengthening Women’s Safety Package (announced in May 2024). These initiatives will strengthen our ambitious agenda to:

- keep women and children safe

- hold people who use violence to account

- stop violence before it starts.

A deep commitment to self-determination

Consistent with Aboriginal self-determination, actions under Dhelk Dja will remain separate to this plan.

The actions under Dhelk Dja have been developed by Aboriginal people for Aboriginal people, in partnership with the Victorian Government.

These actions are monitored by the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum, which includes:

- community-led Dhelk Dja action groups

- Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (ACCOs)

- the Victorian Government.

This plan includes an action to make sure that our broader work to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence is respectful, inclusive and culturally safe for Aboriginal people. This action is designed to complement Dhelk Dja’s work.

Many of the other actions in this plan also aim to make services work better for Aboriginal people, as we continue to build a system that is:

- more inclusive

- better able to respond to individual needs

- driven by skilled and knowledgeable workers.

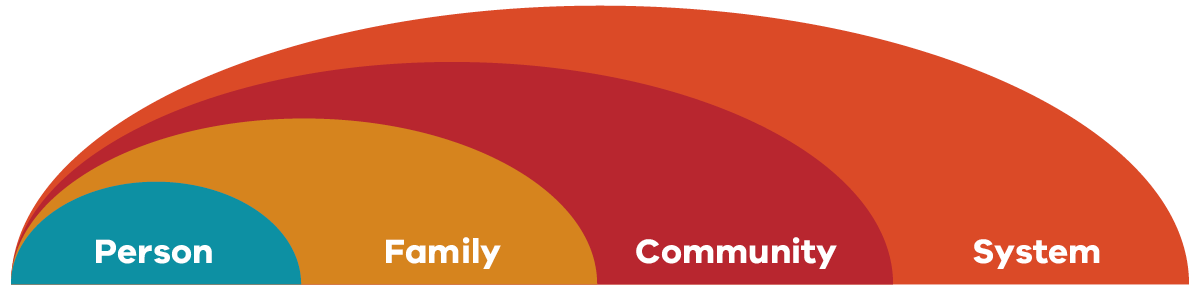

The framework for our actions

The actions in this plan focus on person, family, community and system

The actions in this plan are set out in 4 focus areas:

- Focus area 1: Whole-of-person approach

- Focus area 2: Whole-of-family approach

- Focus area 3: Whole-of-community approach

- Focus area 4: Whole-of-system approach.

This framework recognises that the work to end family and sexual violence needs action at all levels.

Focus area 1: Whole-of-person approach

A whole-of-person approach creates a system that understands and adapts to what people need.

A whole-of-person approach creates a system that understands and adapts to what people need.

Victim survivors need services to be flexible, specialised and wrap around their daily life.

Interventions for people who use violence are most effective when they are tailored to the person’s characteristics and circumstances.

We also need to recognise that a person’s identity and life experiences can shape their beliefs and attitudes about family and sexual violence.

Support for victim survivors will always be at the centre of our work

We will help victim survivors of family and sexual violence:

- connect with specialist support

- have more confidence in the criminal justice system.

This includes trialling Justice Navigators in a new and more coordinated way. This should help survivors of sexual assault who connect with the justice system get the advice and support they need.

We are building a system that can respond to the needs of diverse communities, through targeted services and programs for:

- women from multicultural migrant and refugee communities

- LGBTIQA+ victim survivors

- victim survivors with disability

- women and gender diverse people who have been in prison.

The justice system should enable victim survivors to access support, consider and act on their reporting options, secure a justice outcome (if that’s what they want) and recover.

– Sexual Assault Services Victoria

Addressing the specific needs of children and young people

Since the Royal Commission, we have been improving the family violence system to be more child and youth centred. There are now therapeutic supports and refuges that have been designed for the needs of children and young people as victim survivors.

We are better at recognising that each person’s risks and needs can be different, even among siblings. For example, The Orange Door conducts risk assessments for each child in a family affected by family violence.

The service system must recognise young people as victim-survivors and help-seekers in their own right…

– Centre for Innovative Justice, Melbourne City Mission, Youth Affairs Council Victoria and Berry Street Y-Change

This work has led to change in organisations that interact with children and young people, including:

- police

- schools

- maternal health nurses

- specialist family violence services.

These organisations have had to shift their thinking and practice to make sure children and young people are recognised as victims in their own right.

Children and young people are being positioned as being ‘agents of generational change’ – but the burden of breaking the cycle of family violence cannot solely rest on our shoulders. We need access to age-appropriate, youth specific supports that don’t leave us to bear the brunt of expensive, often out of reach healing and recovery supports.

–Conor Pall, Deputy Chair, Victim Survivor’s Advisory Council

Children and young people continue to describe feeling disempowered and ignored by a family violence system that has not always seen them as victims in their own right.

We need a system that consistently wraps support around children and young people, no matter their age, stage or development. We want children and young people to have agency in decisions about risk, safety planning, healing and recovery.

Children are not a homogeneous group, and their individual circumstances need to be considered when assisting their recovery from family violence.

– Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare

Over the next 3 years, we will make sure the needs of children and young people are recognised and prioritised. We will do this both in our efforts to prevent violence and in our response to it.

We are developing new MARAM practice guidance and tools specifically for identifying and managing family violence safety risks to children and young people. This will help over 6,000 organisations and 400,000 professionals across Victoria (including Victoria Police) to be consistent and coordinated in addressing the needs of children and young people who are victim survivors. This guidance will also enable coordinated responses to young people who use violence.

We will continue to innovate and improve the counselling and therapy available for children and young people to support their recovery from family and sexual violence. This will help them not only rebuild their lives but thrive.

We will refine and embed the approach to children and young people who use violence in the home or display harmful sexual behaviours. We will invest in developmentally-appropriate and therapeutic services to help children and young people get the supports they need.

We will also expand and improve responses to peer-to-peer sexual harm in schools, including harm that occurs online.

Supporting children, young people and their families

In 2023, the Victorian Government announced the establishment of a new Children’s portfolio to improve equity, access and outcomes for Victorian children and families. It puts the needs of the child at the centre of a better-connected system.

The Children’s portfolio brings together important system touchpoints that were spread across different departments and policy areas, including:

- maternal and child health

- early childhood education

- statutory and non-statutory children and family services

- supports for children and young people leaving care services.

This builds on Victoria’s work under Roadmap for reform: Strong families, safe children to shift the children and family services system’s focus from crisis response to prevention and early intervention.

There is also work in progress to expand the Aboriginal-led child and family service system. Wungurilwil Gapgapduir: Aboriginal children and families agreement (‘strong families’ in Latji Latji) is an agreement between:

- the Aboriginal community

- the Victorian Government

- community service organisations.

Wungurilwil Gapgapduir sets out a strategic direction to reduce the number of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care by building their connection to culture, Country and community.

Trauma-capable services for people who use violence

We will work with people who use violence in ways that address the specific factors contributing to their behaviour. This includes:

- challenging harmful beliefs and attitudes towards women

- addressing past trauma

- providing support when there is drug and alcohol dependence or gambling

- making sure there are enough workers with the right skills and capabilities to do this complex work.

We also need to explore new and different ways of blocking pathways to violence. This includes intervening early to support children and young people who have experienced or witnessed violence. This will help them recover and reduce the risk of violence becoming normalised for them.

…early intervention with children and young people entering the system will promote healing and behaviour change.

– Safe Steps Family Violence Response Centre

We are investing in programs for adults who use violence, including specialist programs for:

- fathers

- people from multicultural communities

- people with disability

- Aboriginal people through Aboriginal-led men’s programs.

These programs can help to break or prevent generational cycles of violence.

To end family violence in a generation we must advance research and practice simultaneously, including exploring innovative approaches to working with men.

– No to Violence

By conducting a thorough research study into perpetrators, we will better understand their behaviours and motivations. This will inform our programs for people who use violence and make sure that:

- positive changes to their behaviour continue

- their family members stay safe.

Our actions

Focus area 2: Whole-of-family approach

Recognising a person’s family history and context is important for many people experiencing family and sexual violence. By family, we mean families in all their forms, chosen families and kinship networks.

Recognising a person’s family history and context is important for many people experiencing family and sexual violence. By family, we mean families in all their forms, chosen families and kinship networks.

By taking this approach, we benefit from the leadership of Aboriginal services. These services go beyond individual needs to work with people in their broader family and cultural context. This approach emphasises the different needs and connections between family members.

[O]ur approaches will benefit everyone in Victoria – Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, and will inform Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal services. We want to ensure that our specialist expertise, wisdom, and our whole of family and whole of community approaches are adopted across the system to create a future where everyone can heal, address their trauma and live free from violence.

– Koori Caucus members, Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way

The Orange Door

Our ongoing commitment to The Orange Door is fundamental to the whole-of-family approach.

Before the Royal Commission, police could refer a family to 4 different services following a family violence incident. People did not know where to go for help before things reached crisis point. There was no clear public access point. Families could end up being sent from one referral to another with no actual progress.

This was not an effective system for Victorians who needed help.

The Orange Door changed this. It brings together services that can wrap around a family, getting them the help they need.

The Orange Door helps:

- people experiencing and using family violence

- parents and carers who need help with the care and wellbeing of children and young people.

In doing so, The Orange Door looks at the risks, needs and experiences of all family members and creates a tailored plan to help them.

An interdisciplinary team works together to address immediate safety and child wellbeing concerns, while also connecting people to services that address their longer-term needs. This can include specialist case management support through family violence services and family services, as well as longer-term interventions for people using violence. It can also include a broader range of supports such as help to secure housing, access drug and alcohol services, or to get legal assistance.

We created the Central Information Point and a statewide client database for The Orange Door so that practitioners can access accurate and up-to-date information about all family members. This means The Orange Door practitioners can make better informed decisions and create more effective and tailored strategies for their clients.

We have also supported each Orange Door through an unprecedented investment in senior practice leadership. Each Orange Door network provides Integrated Practice Support, which is delivered by Practice Leaders. Each area-based partnership includes the following Practice Leaders:

- Aboriginal Practice Leader

- Victim Survivor Practice Leader

- Adult Using Family Violence Practice Leader

- Integrated Practice Leader

- Child and Young Person Practice Leader.

The senior roles help guide practitioners in their work with different family members.

Many of the actions in this plan will continue to strengthen and improve The Orange Door, which is still a relatively new and evolving model.

Our actions will include:

- continuing to strengthen Orange Door practitioners’ ability to support children and young people

- helping services within and outside of The Orange Door (such as schools) work better together – so families can get the help they need more quickly and get seamless and coordinated support

- creating a new program to better identify and respond to elder abuse

- continuing to develop Orange Door partnerships so agencies can offer the community an integrated service.

Engaging families to prevent violence before it starts

Families play an important role in preventing violence before it starts. Parents and caregivers can guide young people through early relationships and online environments, helping them develop respectful and safe interactions.

There is an opportunity to promote respectful and equitable relationships when someone becomes a parent for the first time.

We will help new parents challenge gendered expectations and model healthy relationships. By doing this, we can positively influence the beliefs, attitudes and behaviours of the next generation.

Keeping families safe and housed

We help families when violence occurs.

We will continue to improve refuge and crisis accommodation options for victim survivors at immediate risk of harm, including through completion of the refuge development and build program.

Too many women and children are becoming homeless due to family violence – in the current housing crisis, and with family violence occurring at alarming rates, it’s time to think differently and actively change the system to support them to stay safe at home.

– Jocelyn Bignold, Chief Executive Officer McAuley Community Services for Women, Safe at Home launch

We are committed to initiatives that support victim survivors to access a range of safe accommodation options beyond the point of crisis.

The Safe at Home program (launched in March 2025) helps victim survivors stay in their own homes if it is safe to do so. Safe at Home removes the burden of leaving the home from the victim survivor by offering the whole family wraparound supports. This includes supporting the adult using family violence through:

- case management services

- flexible funding so they can find alternative accommodation.

In addition, Personal Safety Initiatives (PSIs) provide tailored security upgrades to improve safety and stability at home.

Women and children who can stay together in stable accommodation of their choice are more likely to feel safe, be financially secure and keep important community connections.

Children and young people can also continue their education, bringing them both short and long term benefits.

We are using all the levers within our control to build more social and affordable housing and house as many people as soon as possible.

The Big Housing Build and Regional Housing Fund will invest:

- $5.3 billion to build 12,000 new social and affordable homes

- $1 billion to build more than 1,300 social and affordable homes in rural and regional Victoria, respectively.

This includes providing 1,000 homes for family violence victim survivors through the Big Housing Build.

As at June 2024, social housing allocations for victim survivors were the highest they have been since the Victorian Housing Register started.

In addition, 10% of all new social housing will be built for Aboriginal Victorians.

We are also investing in new specialised accommodation options for young people on their own. This will give an extra 130 young people in need of housing a safe place to live. These accommodations will be within integrated learning and accommodation centres, known as youth foyers. This will also make it easier for young people to connect to employment and other support services.

Our actions

Focus area 3: Whole-of-community approach

Every Victorian has the power and responsibility to challenge the underlying values and behaviours that lead to family and sexual violence.

Every Victorian has the power and responsibility to challenge the underlying values and behaviours that lead to family and sexual violence.

Strengthening our community-wide approach to preventing family and sexual violence

In 2017, we launched Free from Violence, Victoria’s strategy to prevent violence before it starts. It aims to address the root causes and drivers of family and gendered violence, including attitudes, cultures and systems that:

- downplay violence against women

- limit women’s independence

- impose rigid gender expectations on people, particularly for men to be aggressive, dominant and in control.

This plan continues our work under Free from Violence. It recognises that everyone can learn and change. We need to involve every part of the community, reaching people in practical ways where they live, learn, work and play.

We will explore new partnerships and ways of working with the private and community sectors so we can work together to:

- reduce and end violence

- foster a culture of respect and safety across Victoria.

There is still much to learn about effective practice for primary prevention work that successfully challenges both violence against women and violence against LGBTIQ communities.

– Rainbow Health Australia

For the first time, we are piloting a new, large-scale and place-based approach to preventing and addressing violence – Respect Ballarat: A community model to prevent gendered violence. This model aims to immerse a place with messages and actions to counter violence and its causes, including harmful attitudes, behaviours and inequalities.

Respect Victoria is leading the trial of the ‘Respect Ballarat’ model. The actions, co-designed with the Ballarat community, include:

- conversations

- education and skill building

- community events

- practical changes and resources.

The model makes preventing violence everyone’s responsibility – from people and families to businesses and community organisations.

We will continue to engage people at key life and developmental stages, including:

- as children

- young people

- in older age.

We will become more sophisticated in how we reach diverse groups, including:

- people from LGBTIQA+ communities

- people with disability

- people from different cultural and religious backgrounds.

We will do this through initiatives that are:

- better tailored to each group

- informed by lived experience

- community-led

- meaningful and relevant to the target audience.

We will continue to target the places where Victorians live, work, learn and play – including online spaces.

It is critical that prevention programs consider cultural, social, and technological shifts that impact family and sexual violence.

– Municipal Association of Victoria

Community awareness and understanding of family violence has grown. We now have the opportunity to educate people on forms of family violence that are common but less understood, such as coercive control.

Coercive control… has so many insidious branches or tentacles. They slowly but surely grab hold, increasing their coverage and grip with time until you essentially don't know which part is you anymore. That is only part of the problem, worse can come when the perpetrator senses they are losing control, that is truly the most dangerous time, usually when the victim has decided to leave.

– Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council

Coercive control can be hard to identify or ‘name’, as it often involves isolating victim survivors from their family and friends. Coercive control is linked to risk of serious injury or death.

We want to increase awareness of the signs of coercive control so people can recognise it in their own relationships and help others affected by it.

Supporting children and young people to build respectful relationships

We must protect all children and young people from family and sexual violence, and help those who have experienced it be safe and recover.

To end violence, we must also give children and young people the skills and knowledge to build equal and respectful relationships. Childhood and adolescence are important stages where identity, values and patterns of behaviour are developed.

We will work with young people to help them:

- think critically about online content

- develop healthy identities

- build safe and respectful relationships.

In 2016, we introduced the Respectful Relationships initiative in Victorian schools. Victoria’s Respectful Relationships program helps create lasting change by addressing the attitudes and behaviours that drive violence.

The program helps schools and early childhood educators:

- promote and model respect, positive attitudes and behaviours

- work with children and young people to build safe and respectful relationships, resilience and confidence.

Respectful Relationships education must engage with children and young people outside of formal education settings, be tailored to developmental needs, and be safe, inclusive and accessible to all.

– Centre for Innovative Justice, Melbourne City Mission, Youth Affairs Council Victoria and Berry Street Y-Change

Following an expression of interest during 2024-2025 to expand to further non-government schools, over 2,000 Victorian government, Catholic and independent schools are now signed on to the Respectful Relationships whole-school approach, including all government schools.

Schools also have new Respectful Relationships teaching resources to help students:

- learn how to build and maintain respectful relationships,

- understand consent

- safely navigate online spaces.

Evidence shows that racism is a significant driver of family and gendered violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.[1] It reinforces family and gendered violence against women in culturally and linguistically diverse communities.[2]

We are helping schools address racism and build culturally safe and inclusive learning environments for all First Nations, culturally, linguistically and religiously diverse students, families and carers.

New ways to change attitudes in men and boys that can lead to violence

Violence is most often used by men against women and children.[3] When men are victims of violence, it is usually due to the behaviour of other men.

Harmful gender norms contribute to violence against women. Gender norms are society’s expectations and beliefs about how each gender should behave. Gender norms become embedded at a very young age. They can be reinforced at different life stages through culture and media.

All men have a role to play, not only in challenging their own attitudes and behaviours, but also to help shift the social structures and norms that maintain gender inequality and drive violence against women.

– Our Watch

Gender norms are also harmful to men and boys. Rigid ideas about what it means to be a man can pressure men and boys to look, act or behave in ways that damage their self-esteem, mental health, friendships, and intimate relationships.

Many men and boys want to help create gender equality and end violence against women. But some men and boys are reluctant or find it difficult to challenge disrespectful or hostile attitudes (both their own and others) towards women. This can be due to social pressures and fears of judgement, rejection, and exclusion.[4]

There’s sometimes also fear that if you do step in, are the rest of the group going to back you on it or are you going to be the one person that is sticking up or telling the other person to stop and alienating yourself?

– Participant, Willing, capable and confident: Supporting men to be active contributors to gender equality and the prevention of violence against women

Research shows that men’s peer relationships play a critical role in whether and how men and boys conform to or challenge masculine norms.[5]

In addition, boys and young men can be exposed to extremely sexist and violent content on the internet, including violent pornography.

There are opportunities to build men’s willingness, capability and confidence to become allies for change. We will explore targeted strategies that both:

- engage with men and boys as individuals

- address social and cultural factors that create and enable harmful behaviours and attitudes.

[1] Our Watch, 2018, Changing the picture: A national resource to support the prevention of violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children, Melbourne, Australia.

[2] Our Watch, 2021, Change the story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia (2nd ed.), Melbourne, Australia.

[3] Crime Statistics Agency, In fact: Characteristics of men’s violence against women and girls in police-recorded crime, Number 13, September 2024.

[4] Respect Victoria, 2023, Willing, capable and confident: Supporting men to be active contributors to gender equality and the prevention of violence against women, Respect Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; Our Watch, 2019, Men in focus: unpacking masculinities and engaging men in the prevention of violence against women, Our Watch, Melbourne, Australia.

[5] Respect Victoria, 2023, Willing, capable and confident: Supporting men to be active contributors to gender equality and the prevention of violence against women, Respect Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; Our Watch, 2019, Men in focus: unpacking masculinities and engaging men in the prevention of violence against women, Our Watch, Melbourne, Australia.

Increasing prevention of elder abuse and improving our response to it

Elder abuse can take many forms, including:

- neglect

- emotional abuse

- physical abuse

- sexual abuse

- financial abuse.

The perpetrators are often family members or caregivers, representing a shameful breach of trust.

Elder abuse has unique dynamics and drivers (like ageism) that differ from other forms of family violence. This is why targeted actions are needed to address this form of violence.

Elder abuse is still not well known or understood in Victoria. As Victoria’s population ages, more people will become vulnerable to this form of harm. We must take steps to make sure that older Victorians’ rights, safety and dignity are protected.

There is a pressing need to normalise the recognition of elder abuse as a distinct form of family violence. This can be achieved through concerted efforts in public education, government policy, and professional training.

– COTA Victoria and Seniors Rights Victoria

As part of this plan, we will expand prevention programs to include elder abuse. This will be supported by existing Elder Abuse Prevention Networks.

We will use existing elder abuse training and resources, such as the Elder Abuse Learning Hub, to build engagement and help improve practice. We will also create a practice development program so more specialist family violence practitioners can identify the signs of elder abuse and take action.

Our actions

Focus area 4: Whole-of-system approach

A whole-of-system approach looks at the overarching factors that can work together to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence

A whole-of-system approach looks at the overarching factors that can work together to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence.

This approach recognises how these factors are linked, including:

- laws

- policies and processes

- services

- organisations

- people

- technologies.

It highlights how interconnected and reinforcing actions at every level are vital for ending family and sexual violence.

For example:

- A teacher is trained to recognise the risks and signs of family violence.

- This means the school can intervene early and refer the family to The Orange Door.

- The Orange Door can connect the family to specialist services before violence happens or escalates.

Early intervention may prevent violence and lead to fewer statutory responses being needed.

We must make sure the system works consistently for the benefit of victim survivors and is not exploited by people who use violence.

The family violence sector does not operate in isolation. A strong sector is required to work with people using violence, as well as supporting systems and structures that can complement specialist family violence practice to achieve good outcomes for victim survivors.

– Safe and Equal

Ensuring the system is informed by lived experience

For many years, we have benefited from the expertise of lived experience advocates and committees, including VSAC. Many services have also set up their own lived experience groups to inform their work.

This plan includes several initiatives designed to increase the influence of victim survivors in our work, including:

- championing the role of VSAC across all areas of government

- making sure the newly-established Senior Victorians Advisory Committee’s work program includes a focus on elder abuse.

[Y]outh lived experience leadership is not just beneficial but essential in our shared fight to prevent and address family violence.

– Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council

We will amplify and better connect different lived experience forums to build a more complete picture of the diverse range of people and their experiences.

Some people who have experienced violence choose to work in the public sector or the family and sexual violence sector because they want to help others. Staff members with lived experience bring unique expertise. We should use this to improve and drive changes to policy and service delivery. We will help services to support and value their employees through trauma-informed ways of working.

Improving system and service accountability to Aboriginal people

Cultural safety is a fundamental human right. In practice, it involves:

- making sure initiatives to prevent violence are culturally sensitive

- creating environments where Aboriginal people feel safe to find and get support.

To achieve this, we need strong and well-funded Aboriginal-led organisations, as well as broader services that are safe and welcoming for Aboriginal people. This can only happen through genuine partnership with Aboriginal communities, underpinned by respect for Aboriginal-led approaches.

We will formalise the existing practice of reserving a portion of new family violence funding for ACCOs. Aboriginal-led organisations have a long history of running successful programs to address violence. Providing direct funding is consistent with Aboriginal self-determination.

We are making it easier and more accessible for Aboriginal people to get the qualifications they need for family violence work. We are:

- revising the mandatory minimum qualifications policy for specialist family violence practitioners

- supporting qualification pathways to family violence work – for more on our partnership with Federation University, see priority on Keeping a dedicated focus on our specialist workforce.

We know that family violence and sexual assault services are not always culturally safe for Aboriginal people, which can:

- discourage Aboriginal people from getting help when they experience violence

- further traumatise them when they try to find support.

People working in non-Aboriginal led services need a strong understanding of the impacts of colonisation and intergenerational trauma.

Actions under this plan will also help organisations actively address unconscious bias, racism and discrimination.

There is no end point in achieving cultural safety. Organisations must keep listening, learning and improving all the time.

Services will need to:

- identify and change practices that cause harm to Aboriginal people and their families

- accept and respond to feedback on how they can be safer for Aboriginal people.

Strengthening a system-wide focus on people who use violence

We need a service system that stops people from using violence as early as possible.

We will help services that may have contact with people at risk of using violence to:

- recognise high-risk attitudes and behaviours

- have the confidence to take immediate action to address them.

Embedding effective risk assessment and management is an important way to achieve this.

When violence happens, the justice system must respond quickly and effectively. We will improve:

- intervention orders, which are issued by courts to protect victim survivors

- the stalking offence to make it clearer, and easier to understand and apply.

We recognise that laws alone will not keep people safe from violence. We also need to create behaviour change in people who use violence. We are investing in targeted, trauma-informed programs for people who use violence to help them address the specific factors contributing to their behaviour.

We are committed to making sure victim survivors who attend court feel safe and supported. SFVCs have been designed with extra safety features to create a safer environment. We will continue to refine and improve the SFVC model.

Addressing misidentification

The person who is predominantly using violence in a family or intimate partner relationship is sometimes referred to as the ‘predominant aggressor’.

Misidentification occurs when someone is incorrectly labelled as a perpetrator or predominant aggressor.

This can happen when agencies:

- act on incorrect or incomplete information

- do not recognise their own assumptions, biases or prejudices

- fail to identify patterns of behaviour and risk.

For example:

- a perpetrator may undermine the victim or frame them as the aggressor

- a victim may use violence when acting in self-defence.

This means that systems set up to protect victim survivors can unintentionally cause further harm.

Aboriginal women are disproportionately misidentified as the predominant aggressor. This can have devastating impacts and worsen the violence and racism they are experiencing.

Through MARAM guidance and training, we are improving the skills agencies need to:

- prevent the misidentification of the person using family violence

- make sure steps are taken to correct records

- address the impact on victim survivors when misidentification occurs.

An essential part of protecting victim-survivors involves overcoming the practice of, and mitigating the impacts of, the misidentification of women who have experienced family violence as aggressors.

– Djirra

Regulating activities that contribute to family and sexual violence, including alcohol and gambling

Not all people who gamble or use alcohol are violent. However, alcohol and gambling can worsen the use of violence and its consequences.[1]

Evidence shows that greater access to alcohol increases the risks of family and sexual violence. This is concerning given the recent rapid growth in the online sale and delivery of alcohol.[2] We will review alcohol laws and their impact on family violence victims. We will identify and share best practice and reforms across jurisdictions.

We will work to make sure venues that serve alcohol are safe for patrons and will train staff to identify and respond to behaviours that suggest harassment and family violence.

We suggest a particular emphasis on environments, such as nightclubs, bars and sporting venues and clubs, that correlate with increased levels of domestic, family, and sexual violence.

– No To Violence

We will also introduce reforms to the regulation of electronic gambling machines. We will work with other jurisdictions to develop a national strategy to reduce online gambling harm.

Building the skills and capability of relevant workforces

Since 2018, the MARAM Framework has been the common way to identify, assess and manage family violence risk across different sectors.

At the same time, we also changed laws to make it easier for different services and agencies to share information about risks of family violence (under the FVISS).

These changes have allowed services to:

- work with better information

- manage risk more effectively

- provide more joined-up support.

In some cases, services have had to make big changes to their culture and ways of working.

In this plan, we will embed these changes by continuing to develop this workforce’s skills and knowledge, with MARAM guidance on:

- adults using family violence – to build capability and more effectively respond to people who use violence across the service system

- children and young people – child and young person MARAM practice guides (to be released in 2026) will help children and young people be recognised as victim survivors of family violence in their own right.

We will continue to help organisations align with MARAM and make family violence risk assessment and risk management part of everyday practice. This next phase of work will focus on:

- clarifying, streamlining and consolidating our efforts

- improving how data is used to measure and track outcomes over time

- strengthening the impact of our work.

We will revise the Responding to family violence capability framework (Response Framework), so workers and organisations develop the skills needed to implement MARAM consistently. The Response Framework will identify capabilities workers need to meet their responsibilities. The Response Framework will also guide:

- Vocational Education and Training (VET) and university courses

- professional development activities

- workforce planning.

This will improve the way skills and training systems develop needed capabilities across all workforces related to family violence.

Keeping a dedicated focus on our specialist workforce

Our specialist workforce is vital to our efforts to end violence. These are people who:

- work across the community to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence

- make sure the system is responsive, coordinated and effective.

This workforce should be supported through:

- career pathways

- skills and capability building

- a focus on their health, safety and wellbeing.

[1] N Hing, C O’Mullan, E Nuske, H Breen, L Mainey, A Taylor, A Frost, NGR Kenkinson, U Jatkar, J Deblaquiere, A Rintoul, A Thomas, E Langham, A Jackson, J Lee and V Rawat, ‘The relationship between gambling and intimate partner violence against women’, ANROWS Research report, 21/2020, ANROWS, 2020; P Noonan, A Taylor and J Burke, ‘Links between alcohol consumption and domestic and sexual violence against women: Key findings and future directions’, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety Research report, 8/2017, ANROWS, 2017.

[2] M Livingston, ‘The ecology of domestic violence: the role of alcohol outlet density’, Geospatial Health, 2010, 5(1):139-149; M Livingston, ‘A longitudinal analysis of alcohol outlet density and domestic violence’, Addiction, 2011, 106(5): 919-925; Y Mojica-Perez, S Callinan and M Livingston, ‘Alcohol home delivery services: An investigation of use and risk’, Centre for Alcohol Policy Research and Foundation for Alcohol Research & Education (FARE), 2019; Centre for Innovative Justice, Compulsion, convergence or crime? Criminal justice system contact as a form of gambling harm, RMIT University, 2017.

Since the start of the Royal Commission into Family Violence, the specialist family violence workforce has grown 5 times larger. In 2014, there were around 500 workers. In 2023, there were around 2,500.

We will keep working to make sure there are enough qualified workers to meet the demand for services and help employers address critical vacancies. We will make sure employers make workers’ health, safety and wellbeing a priority.

Under this plan, we will work with education providers to create attractive career pathways into the family and sexual violence workforces. Courses need to stay current with best practice and prepare students for the practical realities of the work.

We are partnering with Federation University on a new Graduate Certificate of Social and Community Services program. In 2026 and 2027, 68 fully-funded places will be available – especially for Aboriginal workers and people living outside metropolitan Melbourne. The new qualification will:

- give workers better access to training

- help attract and retain a diverse and highly skilled family violence workforce that reflects communities across Victoria.

The Community and Social Services Graduate Program is a structured professional graduate program for community services. This pilot program started in 2024 to give new graduates opportunities to start their careers in community services, including family violence and sexual assault services. This program recognises that supporting someone effectively in their first year can set them up for a long and successful career and make it easier to build and retain skilled workers.

To attract workers who want to make a difference in the family and sexual violence sectors, we need organisations to offer a range of roles that are:

- satisfying

- well supported

- offer meaningful career progression.

Organisations also need to invest in:

- onboarding

- supervision

- learning and development opportunities

- looking after their workers’ health, safety and wellbeing.

We are trialling innovative ideas to boost the number of skilled workers. One example is the Workforce Vacancies Demonstration Program. This program involves 4 lead organisations trialling ideas, such as:

- cross-agency secondment

- shared induction

- learning and development

- mentoring.

It is also looking to better support staff from diverse backgrounds and encourage students to do work experience in specialist services.

Through these changes, we will have a vibrant, skilled and supported workforce that is ready to meet the challenge of ending family and sexual violence.

Once people are part of the specialist family violence workforce, we want them to have job security and be able to see a future for their career in our sector.

– Safe and Equal

Improving the coordination of services, policies and programs for better support

We will promote consistency and collaboration across a broader range of services.

For example, Respect Victoria will introduce quality principles to help put in place quality and evidence‑informed primary prevention programs in different settings and sectors. This will lead to greater consistency in how programs are designed and implemented, so they can have the greatest effect possible.

Without sufficiently resourced, coordinated and evidence-based primary prevention activity, we cannot hope to achieve the level of cultural and behavioural change required to break the cycle of family violence…

– Respect Victoria

We will encourage better integration across mental health and victim services. We will improve access and intake to mental health services for victim survivors.

We will build an understanding of the connections between:

- family violence

- sexual offending

- suicide.

This will help:

- identify key intervention points

- improve referral pathways

- strengthen service responses.

Improving how we measure our impact

We need to make sure that the changes we are making to end family and sexual violence are working. Every dollar we invest in addressing violence should make a difference.

We will keep building our understanding of what works to prevent violence and refine our strategies accordingly.

The family violence sector has traditionally been valued by reference to the number of people who use a service, rather than the complexity of needs and the outcomes achieved. The focus on ‘throughput’ undermines the multifaceted, intersecting and diverse needs of people seeking help for family violence.

– Safe Steps Family Violence Response Centre

By consistently collecting data across the family violence and sexual assault systems, we can identify trends and track outcomes over time. This includes developing a better understanding of:

- what happens as people progress through the system

- how effective broader programs and services are.

Data can help us make sure services are sustainable in the long term. We can use date to understand how much funding is needed to meet current and future demand.

We will link data we collect to the Family Violence Outcomes Framework so we can:

- track our collective impact

- be transparent

- make sure we meet our commitments

- contribute rigorous data to national efforts to measure progress to end violence.