- Published by:

- Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

- Date:

- 4 Dec 2023

This document is for you, the Victorian community.

It tells you what we have done so far - the strong foundation we will build on. It also talks about the things we still need to do – the unfinished business.

Our work during the next three years will focus on five key priorities:

- drive down family and sexual violence

- focus on children and young people

- strengthen support for victim survivors

- respond to change

- understand and demonstrate our impact.

As we do this work, we remain committed to Aboriginal self-determination. We will continue to put lived experience at the heart of everything we do. We will continue to address Victorians’ diverse needs and the barriers they may face to seeking help.

What we need next is concrete actions, timeframes and a clear understanding of who is responsible for what. We will work closely with the people who prevent and respond to family violence across our state to develop these.

These actions will be set out in the third and final Rolling Action Plan for the 10-year plan, which will be released in mid-2024.

It is going to take a lot of hard work and dedication to stop family violence in Victoria.

Every Victorian has a role to play. We invite you to join us in this important mission.

This document will guide us in the journey.

If you would like to get involved, head to Engage Victoria before Sunday 4 February 2024 and tell us how you think we can deliver on our priorities and focus areas.

Foreword from the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Our goal is to end this violence. This requires unwavering work toward generational change.

Eight years ago, the Royal Commission into Family Violence revealed the devastating extent and hurt of family violence across Victoria. Its 227 recommendations were bold and broad ranging and the Victorian Government promised to implement every single one of them.

In partnership with the family violence sector, we embarked on an ambitious 10-year plan to transform the way Victoria prevents and responds to family violence. This plan has been backed by investment of $3.86 billion – more than all other states or territories combined.

Through the hard work of many people across our state, the Royal Commission recommendations have been implemented and they are making a difference.

Because of our reforms more Victorians are aware of family violence and how to seek help.

- For those who are seeking help, they can now access The Orange Door Network in their local area and be connected to the services they need.

- Victorians who choose to commit violence are more likely to be held accountable for their behaviour and engaged to change it.

- Victorians working in a range of frontline services are better equipped to identify and manage the risk of family violence.

- Victorian children are learning about respectful relationships and young people are learning about affirmative consent.

We have come a long way as a state since 2015 and Victorians should be proud of this.

But we know there remains a long way to go. Too many Victorians continue to use violence and too many continue to experience its damaging consequences.

Our goal is to end this violence. This requires unwavering work toward generational change. We cannot step back from this challenge. It is our unfinished business.

As we now move beyond the Royal Commission recommendations, we will target our efforts where they can have the greatest benefit.

We will focus on prevention to drive down family violence. We will strengthen support for victim survivors and accountability for people who use violence. We will prioritise the safety and agency of children and young people. We will respond to the rapid cultural, social and technological shifts taking place around us. We will track our progress and measure our success.

We will continue to work across Victoria’s diverse communities, including continuing our partnership with Aboriginal communities. The lived experience of victim survivors will continue to guide this work. I extend my deepest gratitude to the many dedicated people across our state who have worked hard on Victoria’s reform to date, and who will continue to support this reform. I acknowledge and thank the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council, the Dhelk Dja Koori Caucus members, and our invaluable partners in the family violence sector. Your unwavering dedication and effort has been central to our progress.

With your help, we will now take the next steps toward ending family violence in Victoria.

Vicki Ward MP

Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

Statement from Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council

The creation of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council has enabled people with lived experience to shape policy and service design.

We, the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council, are a collective of diverse individuals. Our experiences, ideas and perspectives are different. Given the pervasiveness of family violence, we can never represent all voices, but we have one shared heart in knowing the profound cost of violence to individuals and communities and the urgent need to confront this crisis.

We stand on the shoulders of the strong advocates and survivors who have spoken out against all forms of abuse and violence with great courage, resilience, and bravery – to prevent others from experiencing the same pain and suffering. We have immense gratitude for those who have done and continue to do this work.

The creation of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council has enabled people with lived experience to shape policy and service design. It allows decision makers to learn about systemic failures, and to hear first-hand the impact violence has on victim survivors. Lived experience must be valued in professional spaces for the specialist skill it is and welcomed into every level and at every stage of policy making on family violence.

Lived experience is not about stories of trauma. You shouldn’t need to hear our stories to be inspired to take action. So much is asked of victim survivors. We experience harm both from the people who use violence against us and from the systems and institutions which are supposed to protect and support us. These actions not only harm us but continue to define us. We suffer the experience of violence and then we are held responsible to solve it. We are expected to survive after surviving.

Responses to family violence must be informed and developed in partnership with victim survivors, but the responsibility for ending family violence against women, children and young people is not our burden to bear. This responsibility is, and always has been, with those who choose to use violence, in all its many forms. This could be our parent, our child, our partner, our sibling, or someone else close to us, but overwhelmingly those who choose to use violence are men.

Ending family violence is not about men versus women. It’s not about us versus them. Violence affects all of us, and ending violence depends on all of us.

Words have power. Language is a framing tool which constructs our understanding. It influences narratives and world views. When we don’t include men who use violence in conversations about violence, we allow them to remain hidden.

To truly eliminate family violence, we need to place those who are at the root of the problem in the centre of the frame - those who choose to use violence, not the ones experiencing violence. People don’t just experience family violence. It doesn’t just happen.

We know that 1 in 6 women experience violence, but we don’t talk about who uses violence. We’re left to assume. We, the victim survivor, are front and centre, but they, those who choose to use violence, sit outside the frame.

Men who use violence don’t look like monsters. Those who cause the most harm are often the most likeable within a community. To the world, they don’t present themselves as threatening men - that’s what makes them so dangerous. They aren’t exceptions to the norm or outliers of society. Their violence isn’t a deviation from our culture – it is because of it.

Violence creates violence. It is a cycle born out of suffering and trauma. When we exclude men from conversations about violence, we do them a disservice. We deny their experiences, we deny their suffering, and we remove opportunities for healing and redemption. Accountability and compassion go hand in hand– by holding people who use violence accountable, we create an opportunity for change. We are not here to indict men, but to invite them to be a part of the solution.

Violence is an individual choice but a collective community responsibility. It is all of us, together, versus the factors and conditions that enable violence. Violence impacts us all, whether you realise it or not. It doesn’t discriminate based on race, age, religion or sexuality. We all have a role to play in confronting, healing, and preventing abuse from happening in the first place.

What you allow to exist, persists. What you choose to ignore or not see is what you accept.

Silence is an intentional act of complicity. When you don’t speak up, you are supporting the culture and attitudes that create violence.

Actions also have power. We ask all people and institutions to put those who choose to use violence at the centre of all conversations and reforms. Now is the time to redirect the lens.

Holding those who choose to use violence to account is necessary to prevent all forms of violence, alongside offering opportunities for recovery and healing.

Let’s put the burden where it belongs. Put those to blame in the frame.

Introductory acknowledgements

We acknowledge country, we are committed to truth-telling and Treaty and we recognise those who have been harmed by family violence.

We acknowledge Country

The Victorian Government acknowledges Victorian Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water on which we rely.

We recognise those who have been harmed by family violence

The Victorian Government recognises those who have experienced violence at the hands of someone close to them, including adults, older adults, children, young people and those within our workforce.

Content warning

This document contains reference to and descriptions of acts of family and sexual violence.

Language statement

These terms aim to support more people to see themselves and their experiences in this document.

We acknowledge Country

The Victorian Government acknowledges Victorian Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water on which we rely.

The Victorian Government acknowledges Victorian Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We acknowledge and respect that Aboriginal communities are steeped in traditions and customs built on a disciplined social and cultural order that has sustained 60,000 years of existence. We acknowledge the significant disruptions to social and cultural order and the ongoing hurt caused by colonisation.

We acknowledge the ongoing leadership role of Aboriginal communities, particularly Aboriginal women, in addressing and preventing family violence and will continue to work in collaboration with First Peoples to eliminate family violence from all communities.

We are committed to truth-telling and Treaty

We acknowledge the impact of colonisation to this day, including discrimination in the way that our structures and systems operate.

We acknowledge the impact of colonisation to this day, including discrimination in the way that our structures and systems operate.

We seek ways to rectify past wrongs and are deeply committed to Aboriginal self-determination and to supporting Victoria’s Treaty and truth-telling processes.

We acknowledge that Treaty will have wide-ranging impacts for the way we work with Aboriginal Victorians. We seek to create respectful and collaborative partnerships and develop policies and programs that respect Aboriginal self-determination and align with Treaty aspirations.

We acknowledge that Victoria’s Treaty process will provide a framework for the transfer of decision-making power and resources to support self-determining Aboriginal communities to take control of matters that affect their lives. We commit to working proactively to support this work in line with the aspirations of Traditional Owners and Aboriginal Victorians.

We recognise those who have been harmed by family violence

The Victorian Government recognises those who have experienced violence at the hands of someone close to them, including adults, older adults, children, young people and those within our workforce.

The Victorian Government recognises those who have experienced violence at the hands of someone close to them, including adults, older adults, children, young people and those within our workforce. Our efforts to prevent and respond to family violence are for them. It is vital that policies and services are informed by their experiences, expertise and advocacy.

We also remember and pay respects to those who did not survive and acknowledge all of those who have lost loved ones to family violence.

We keep at the forefront of our minds all those who have been, or continue to be, harmed by family or sexual violence, and acknowledge their ongoing courage and resilience.

Content warning

This document contains reference to and descriptions of acts of family and sexual violence.

This document contains reference to and descriptions of acts of family and sexual violence.

If you have experienced violence or sexual assault and need immediate or ongoing help, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) to talk to a counsellor from the national sexual assault and domestic violence hotline. For confidential support and information, contact Safe Steps’ 24/7 family violence response line on 1800 015 188.

If you have concerns about your safety or that of someone else, please contact the police in your state or territory, or call Triple Zero (000) for emergency help.

Language statement

These terms aim to support more people to see themselves and their experiences in this document.

Family violence is the use of violence by a current or former intimate partner or family member. This includes people who share a family-like relationship with the person they are harming. For example, it includes unpaid carers, housemates, chosen family and kinship connections for Aboriginal people. Family violence is not just physical. It also encompasses emotional, psychological, sexual, cultural and financial abuse and neglect. This includes threatening, coercive and controlling behaviours.

Sexual violence, or sexual assault, is a type of violence in which any sexual act is attempted, or occurs, without consent. Sexual violence can be a form of family violence. It can also be perpetrated outside of a family context.

We use the term ‘family and sexual violence’ when talking about our work to prevent violence. This is when we seek to change the attitudes, beliefs and behaviours that contribute to both forms of violence.

When we talk about ‘sexual violence’ in this document, we mean sexual violence within a family or family-like relationship.

We are developing a dedicated sexual violence strategy. This strategy will help us coordinate and improve the way we respond to all forms of sexual violence.

We acknowledge the significant role that sexual assault services play in supporting people who experience sexual violence, including as a form of family violence. Their work is vital, and we will continue to support them so victim survivors receive the specialist response they need.

Violence against women refers to violence directed at a woman because she is a woman or violence that affects women disproportionately [1]. The term ‘women’ includes cisgender, trans and gender diverse women and sistergirls.

Gender-based violence refers to violence that is used against someone because of their gender. While people of all genders can experience gender-based violence, the term is most often used to describe violence against women and girls. This is because most gender-based violence is perpetrated by heterosexual, cisgender men against women, because they are women[2].

The Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council guided us on the terms we use to refer to people who are harmed by family violence and those who use violence. We acknowledge that people who are harmed by family violence have different ways they choose to identify themselves and others. We cannot capture all identities and experiences but acknowledge the importance of each person choosing how they identify.

This is why we use the terms victim survivor and person who has experienced violence interchangeably. ‘Victim survivor’ includes those who may identify more with the ‘victim’ or the ‘survivor’ term at different points of their journey. Some people may also feel they have progressed beyond being a survivor.

We also use the terms person who uses violence and perpetrator interchangeably. Both terms emphasise the violent behaviour. However, one may be more appropriate than the other depending on the cultural context or preference of the victim survivor.

These terms aim to support more people to see themselves and their experiences in this document.

The words ‘our’ and ‘we’ in this document refer to the Victorian Government.

References

[1] Our Watch 2021, Change the story: a shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia, 2nd ed., accessed 26 June 2023.

[2] Commonwealth of Australia 2022, National plan to end violence against women and children 2022-2032.

Our work to end family violence

Your family, whatever form it takes, should make you feel safe, loved, supported and respected. Sadly, this is not always the case.

Sometimes, people use violence in their closest relationships. When they do this, they take away their family’s sense of safety. Fear may replace love. Control may replace support. Ridicule may replace respect.

Most often, it is men who choose to use this violence against women and children [1]. However, partners of any gender can use violence. Parents, siblings and children can use violence. Chosen, kinship and other family members can also use violence.

The impacts of this violence are often devastating. They may be physical, emotional, psychological, financial, social, educational and developmental [2]. These impacts can be felt across the community and from one generation to the next, creating cycles of violence.

This is why, in 2015, the Victorian Government established Australia’s first Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission). The Royal Commission heard directly from the community to find out what we need to do to prevent family violence, improve support for victim survivors and hold those who use violence to account.

In response to the Royal Commission, we developed a bold and ambitious 10-year plan for change, called Ending family violence: Victoria's 10-year plan for change. Through this plan, we have implemented every single one of the Royal Commission’s 227 recommendations. The plan is backed with more than $3.86 billion of investment.

We are now at a crucial stage of our reform journey.

The next phase of our work must get us closer to delivering on the intent of the Royal Commission. Together with you, the Victorian community, we want to achieve a future where all Victorians are safe, thriving and living free from family and sexual violence and abuse.

Our message to victim survivors is clear:

We see you. We hear you. We believe you.

We acknowledge the profound effects this violence has on you.

We will take action to stop this violence. And we will support you to be safe and recover.

About this document

This document is for you, the Victorian community.

It tells you what we have done so far - the strong foundation we will build on. It also talks about the things we still need to do – the unfinished business.

Our work during the next three years will focus on five key priorities:

- drive down family and sexual violence

- focus on children and young people

- strengthen support for victim survivors

- respond to change

- understand and demonstrate our impact.

As we do this work, we remain committed to Aboriginal self-determination. We will continue to put lived experience at the heart of everything we do. We will continue to address Victorians’ diverse needs and the barriers they may face to seeking help.

What we need next is concrete actions, timeframes and a clear understanding of who is responsible for what. We will work closely with the people who prevent and respond to family violence across our state to develop these.

These actions will be set out in the third and final Rolling Action Plan 2024-2026 under the 10-year plan, which will be released in mid-2024.

It is going to take a lot of hard work and dedication to stop family violence in Victoria.

Every Victorian has a role to play. We invite you to join us in this important mission.

This document will guide us in the journey.

References

[1] Our Watch 2019, Men in focus: summary of evidence in review, accessed 7 June 2023.

[2] AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019, cat. no. FDV 3, Canberra.

A strong foundation is now in place

We have now spent seven years working on Ending family violence: Victoria's 10-year plan for change. During this time, we have made big changes to the way we prevent and respond to family violence. We are proud of just how far we have come.

This has been a period of fast-paced, wide-scale change led by many resolute people across our state.

This includes people and organisations who work to prevent and respond to family violence and sexual violence and many others across our community who play a vital role in making our state a safer place for all Victorians.

This change builds on decades of effort by the people who came before us. This work began in the 1970s, with women’s groups who helped women and children experiencing family violence [1].

Our reform journey so far

We have now spent seven years working on our 10-year plan.

Key achievements

Our work so far has transformed the way we prevent and respond to family violence.

References

[1] State of Victoria 2016, Royal Commission into Family Violence: summary and recommendations, Parl Paper no. 132 (2014–26).

Our reform journey so far

We have now spent seven years working on our 10-year plan.

2015

- The Royal Commission into Family Violence is established.

- Victoria Police establishes Australia’s first dedicated Family Violence Command.

2016

- The Victorian Government accepts all 227 recommendations of the Royal Commission.

- The inaugural Victim Survivors Advisory Council (VSAC) is established.

- Risk Assessment and Management Panels are rolled out across the state, to conduct multi-agency assessment of people at high risk of harm from family violence.

- Caring Dads program commences to prevent fathers committing family violence

- Ending family violence: Victoria’s 10-year plan for change is launched

2017

- Family Safety Victoria is established.

2018

- Dhelk Dja Agreement between Aboriginal communities and services and the Victorian Government to prevent and respond to family violence against Aboriginal people.

- Respect Victoria is established.

- The Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM), Family Violence Information Sharing (FVIS) Scheme and the Central Information Point are launched.

- The first of 18 The Orange Door sites opens.

- Implementation of minimum standards for men’s behavioural change programs.

2019

- The first ‘core and cluster’ refuge opens.

- The first of 13 Specialist Family Violence Courts commence operation.

- The Centre for Family Violence opens at the Victoria Police Academy.

2020

- The Family Violence Jobs Portal is launched.

- Men's Accommodation and Counselling Services is established

2021

- The Gender Equality Act 2020 comes into effect.

- All Victorian government schools signed onto the Respectful Relationships initiative.

- Mandatory minimum qualifications for family violence practitioners introduced.

2022

- The Family Violence Memorial is unveiled.

2023

- All 227 Royal Commission recommendations implemented

- The first of three Aboriginal Access Points to The Orange Door Networks opens.

Key achievements

Our work so far has transformed the way we prevent and respond to family violence.

Preventing family violence

- More than 1,950 Victorian schools, including all government schools, provide the Respectful Relationships initiative to support children and young people to build healthy relationships.

- 37,500 school staff and 3,800 early childhood educators have participated in the Respectful Relationships professional learning.

- An evaluation of Respect Victoria’s June 2021 Call it Out campaign found that almost half (49 per cent) felt the advertisement helped them better understand the importance of respecting women, and 51 per cent felt it made them more comfortable to talk about what respect means with others.

- More than 250 prevention initiatives have been launched in the places where Victorians live, work, learn and play.

Supporting victim survivors

- 14 new ‘core and cluster’ refuges provide safe and private independent unit accommodation to victim survivors, with more in development.

- 8,000 Flexible Support Packages were provided to victim survivors in 2021–22, giving them the opportunity to direct their own pathway to safety, healing and independence.

- 303,000 people, including 136,000 children, have accessed support through The Orange Door network since it commenced operation in 2018.

Intervening with people who use violence

- 25,980 people using violence have engaged in perpetrator interventions since July 2017.

- Approximately 1,040 children and young people, and their families, participate in the Adolescent Family Violence in The Home program each year.

Strengthening police and justice responses

- 13 new Specialist Family Violence Courts are operating across Victoria providing specialised and trauma-informed support and infrastructure.

- 29 specialist Victoria Police Family Violence Investigation Units are operating across Victoria.

- 18,096 family violence training qualifications were obtained through the Victoria Policy Academy’s Centre of Learning for Family Violence since its commencement in 2019.

Sharing information and managing risk

- More than 20,400 reports on perpetrators have been produced through the Central Information point since it commenced in April 2018.

- More than 107,000 professionals from over 6,000 government and non-government organisations have undertaken training to identify and manage family violence risk since 2018.

- Since commencement of the Family Violence Information Sharing (FVIS) Scheme in 2018, information about family violence has been shared more than 118,000 times by key government agencies alone.

Self-determination

- More than 300 Aboriginal-led projects have been funded under the Aboriginal Community Initiatives Fund.

- 5 Aboriginal sexual assault support services are using culturally safe healing approaches to respond to the needs of Aboriginal victim survivors of sexual violence.

Embedding lived experience

- 34 victim survivors have contributed to the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council through three councils since 2016.

Supporting diverse communities

- More than 7,300 people across 45 multicultural and five faith communities have been engaged through the Supporting Multicultural and Faith Communities to Prevent Family Violence Grant Program.

Building a strong workforce

- An estimated 2,000 new workers have been added to the family violence workforce since 2014.

- 1,789 students have undertaken placements through the Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work program.

- 444 trainees and graduates have participated in the Family Violence and Sexual Assault Traineeship and Graduate Programs.

The task ahead

Our work so far has transformed the way we prevent and respond to family violence. Our work needs time to take effect.

Our work so far has transformed the way we prevent and respond to family violence. However, we have not yet delivered the full extent of the vision of the Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission).

We are only part-way through our plan. Our work needs time to take effect.

We know we must continue with this unfinished business.

Many Victorians continue to use violence against intimate partners and family members. This violence cuts lives short and causes lifelong harm.

It also places an enormous burden on our economy.

We simply cannot afford to step back from this challenge.

We need to disrupt the cycle of family violence. If we don’t, the costs to people’s lives will continue to be devastating and the costs to the economy will be unsustainable.

How many people are being harmed by family violence in Victoria now?

- 92,296 family violence incidents were reported [1]

- 41% of recorded sexual offences related to family violence [2]

- 66,309 individuals or families were referred for support through The Orange Door network [3]

Who experiences family violence?

Violence against people of different ages

From July 2021 to June 2022 in Victoria:

- 5,258 family violence incidents were perpetrated against a person aged 65 or older [4]

- 33,240 family violence incidents had children present [5]

- 34,437 referrals to The Orange Door network included at least one child [3]

The gendered nature of family violence

From July 2021 to June 2022 in Victoria:

- 73% of people who were reported as perpetrators of family violence were male [6]

- 71% of people who had family violence perpetrated against them were female [4]

- 61% of children who had family violence perpetrated against them were girls [4]

- 63% of people over the age of 65 who had family violence perpetrated against them were women [4]

Violence against Aboriginal women and children

Family violence is not part of Aboriginal culture or Aboriginal identity. However, it has a disproportionate impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Victoria. This is particularly the case for women and children.

This impact is the same whether Aboriginal people live in rural, regional or urban areas.

A significant proportion of family violence and violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children is perpetrated by non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men from many cultural backgrounds [7].

Family violence also contributes to the increasing criminalisation of Aboriginal women in Victoria. This is because a significant proportion of Aboriginal women in prison have experienced family violence or sexual abuse [8].

Aboriginal women are:

- 45 times more likely to experience family violence than non-Aboriginal women [9]

- 25 times more likely to be killed or injured from family violence than non-Aboriginal women [9]

Experiences of violence across our community

Particular communities face a greater risk of family violence. They include multicultural and multifaith communities, LGBTIQ+ communities, people with a disability, sex workers and women in or exiting prison.

Together with people living in rural and regional areas, these groups may also face barriers when they seek help. This is because their experiences of family violence may be less visible and less well understood [10].

When people identify with more than one of these communities, the risks and challenges can be heightened.

- Women with disability are almost 2 times more likely to experience physical or sexual violence from a partner than women without disability [11]

- 43% of LGBTIQ+ Victorians have been abused by an intimate partner [12]

- 70-90% of women in custody have experienced abuse [13]

- 38% of LGBTIQ+ Victorians have been abused by a family member [13]

- The Orange Door network has provided support to 141,565 people in regional/rural areas since 2018

- Women from refugee backgrounds are particularly vulnerable to financial abuse, reproductive coercion and immigration-related violence [14]

Is family violence decreasing in Victoria?

Reports of family violence to police appear to have stabilised in recent years. However, we do not yet know if family violence has peaked.

This is because many people do not report their experience of family violence to police or seek any help.

In fact, more than a third of people who have experienced physical violence [15], and half of those who have experienced sexual assault, have not yet sought help [16].

After the Royal Commission, we set out to reduce this gap between the number of family violence incidents in Victoria and how many of those are reported. We worked to increase people’s understanding of family violence, so it was easier to identify. We strengthened the way we respond to family violence so more people would feel confident to report it or seek help.

Success would mean reports would increase at first and this is exactly what happened. Reports of family violence steadily increased in the early years of Ending family violence: Victoria's 10-year plan for change.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have also contributed to this increase. Family violence workers reported that, during the pandemic, there were more first-time reports of family violence, and those reports were more likely to involve severe violence [17].

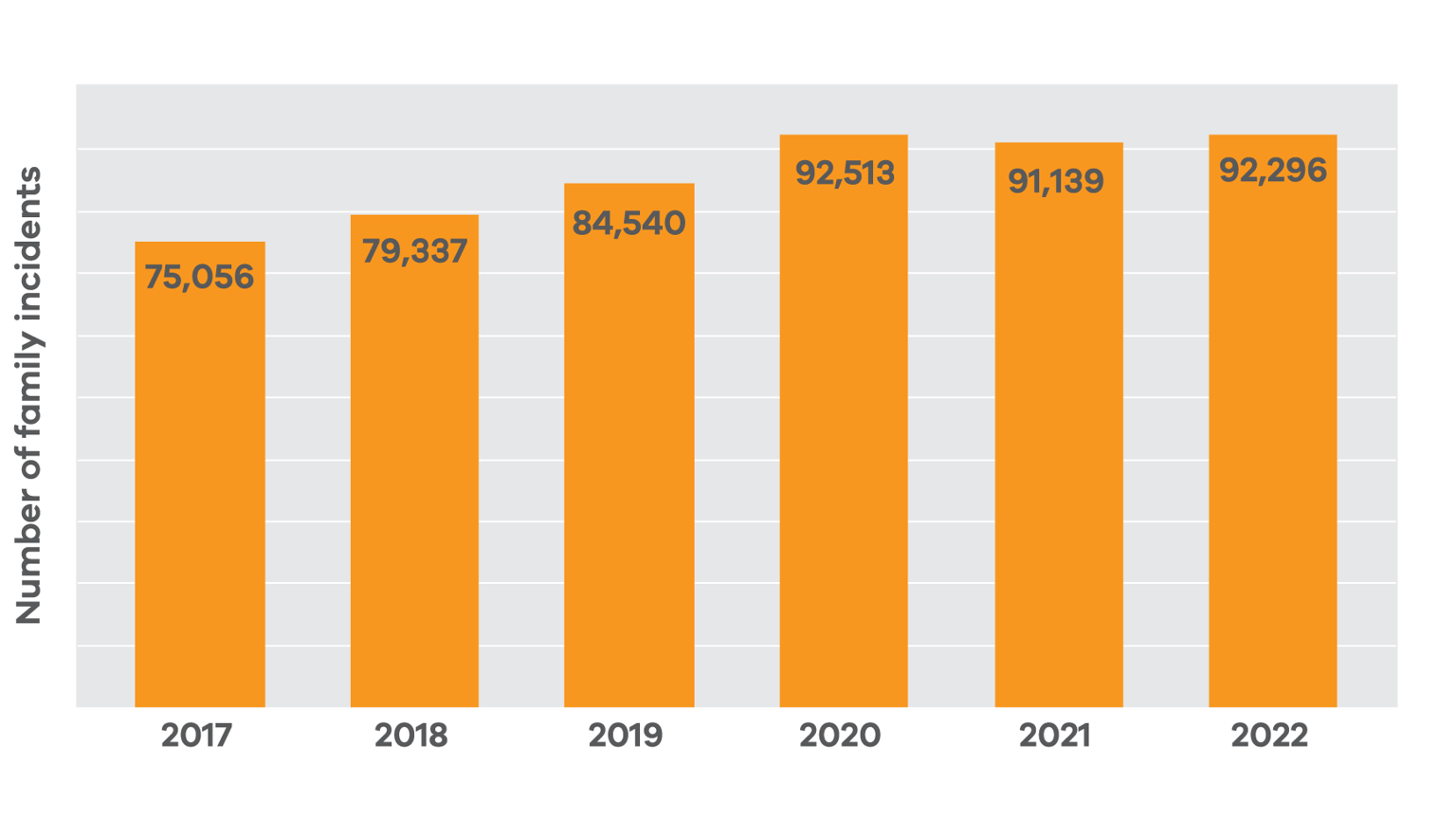

Reports of family violence now look like they are levelling off. However, they are 23 per cent higher than they were in 2017. Reports have increased from 75,056 in 2017 [18] to 92,296 in 2022 [19].

We do not yet have all the data we need to truly understand the extent of family violence in the community.

While we work to build this data, we will continue to focus on reducing the gap between prevalence and reporting so we can be confident no one is left behind as rates of violence fall.

We are also doing ground-breaking work to see if we can predict when family violence will peak and then decline in Victoria.

References

[1] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2023a, Key figures: year ending December 2022, accessed 7 June 2023.

[2] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2022a, Victoria Police data tables (2021–2022): Table 21. Offences recorded by offence categories and family incident flag, July 2017 to June 2022, accessed 4 July 2023.

[3] Family Safety Victoria 2022, The Orange Door annual service delivery report 2020–21: referrals and access, State of Victoria, accessed 26 June 2023.

[4] CSA Crime Statistics Agency) 2022b, Victoria Police data tables (2021–2022): Table 4 Affected family members by sex and age July 2017 to June 2022, accessed 1 August 2023.

[5] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2023b, Family incidents: T1 family incidents recorded and rate per 100,000 population, accessed 9 June 2023.

[6] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2022c, Victoria Police data tables (2021–2022): Table 6 Other parties by sex and age July 2017 to June 2022, accessed 8 June 2023.

[7] Our Watch 2023, Challenging misconceptions about violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, accessed 7 June 2023.

[8] VEOHRC (Victorian Equal Opportunities and Human Rights Commission) 2013, Unfinished business: Koori women and the justice system, State of Victoria, accessed 26 June 2023

[9] State of Victoria 2021a, Family violence reform rolling action plan 2020–2023: Aboriginal self-determination, accessed 7 June 2023.

[10] State of Victoria 2021b, Everybody matters: inclusion and equity statement, accessed 20 June 2023.

[11] People with Disability Australia and Domestic Violence NSW (PWDA and DVNSW) 2021, Women with disability and domestic and family violence: a guide for policy and practice, accessed 22 June 2023.

[12] Department of Families, Fairness and Housing 2022, Pride in our future: Victoria’s LGBTIQ+ strategy 2022–32, State of Victoria.

[13] ANROWS (Australian National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) 2020, Women’s imprisonment and domestic, family, and sexual violence: research synthesis, accessed 22 June 2023.

[14] AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) 2018, Intimate partner violence in Australian refugee communities, accessed 22 June 2023.

[15] AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2022a, Family, domestic and sexual violence data in Australia, accessed 7 June 2023

[16] AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2020 Sexual assault in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 7 June 2023.

[17] Pfitzner N, Fitz-Gibbon K and True J 2020, Responding to the ‘shadow pandemics’: practitioner views on the nature of and responses to violence against women in Victoria, Australia during the COVID-19 restrictions.

[18] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2016, Predictor of recidivism amongst police recorded family violence perpetrators.

[19] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2023c, Family incidents, accessed 7 June 2023.

Getting the job done

We have a strong foundation in place. However, we still face big challenges. These will be the focus of the final stage of Ending family violence: Victoria's 10-year plan for change.

We will do this work in partnership with Aboriginal people. We will listen to people who have experienced violence, including children and young people. We will draw on the expertise of people working to prevent and respond to family violence across Victoria.

The work of Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor will also help us.

The Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor (FVRIM) was set up as an independent statutory officer of the Parliament after the Royal Commission Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission). Its task was to monitor and review how we implemented the Royal Commission recommendations.

The FVRIM completed its monitoring program this year. It released its final report in January 2023.

The FVRIM’s insights and suggested actions will shape our approach to the next stage of reform in Victoria.

Every level of government – national, state and local – has a job to do to help end family violence.

Across Victoria, many councils are actively working to prevent violence through the vital services they provide to local communities.

At the national level, action is being taken under the new 10-year National Plan to End Violence Against Women and Children 2022–2032 (the national plan). The five priorities set out in this document have been developed to align with the national plan. If we combine our efforts with the efforts of other governments, we can be more effective. We know that the same attitudes and behaviours drive violence against women across Australia. That violence doesn’t stop at state borders.

Our unwavering commitments

From the very beginning, we have worked to be inclusive, equitable and accessible in the way we prevent and respond to family violence.

Three overarching principles underpin and guide everything we do:

We are committed to Aboriginal self-determination. This will support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be culturally strong, safe and free from violence. We will partner with Aboriginal communities as they determine, design and implement solutions. In addition, we will support broader government services to be culturally safe for Aboriginal people. This will help redress the discrimination that stems from colonisation.

Dhelk Dja – a partnership with Aboriginal communities to address family violence

Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families, is an Aboriginal-led agreement to address family violence in Aboriginal communities.

We value lived experience. People with experience of family and sexual violence are at the heart of our work. They also help shape it. More than anyone else, they understand the effects of this violence. They know what it is like to seek help, rebuild and recover. We must – and will – continue to listen to them. We will provide meaningful opportunities for people with lived experience to guide our approach, including through the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council.[1]

Family Violence Lived Experience Strategy

The strategy calls on government and the sector to embed lived experience across the full spectrum of family and sexual violence reform.

We include all Victorians and address their diverse needs. Family violence and sexual violence intersect with other experiences of inequality and discrimination. These include inequality because of a person’s age, gender, sex, sexuality, ability, ethnicity, culture, language, religion, visa status, caring responsibilities, geographic location or socioeconomic status. When inequality occurs because of more than one of these factors, it is usually worse. We will continue to tailor our policies and programs, so they are effective for a diverse range of Victorians.

Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement

The statement sets out the Victorian Government’s 10-year vision for a family violence system that is more inclusive, safe, responsive and accountable.

These are our unwavering commitments, and they will continue to evolve to reflect what we learn over time. This includes in the context of Victoria’s Treaty and truth-telling process and the Yoorrook Justice Commission.[2]

Footnotes

[1] In 2016, we established the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council to give people with lived experience of family violence a formal voice and provided opportunities for consultation on government policies and programs relating to family violence.

[2] Victoria's formal truth-telling process, the Yoorrook Justice Commission (the Commission), is also under way. The Commission is gathering evidence on the systemic injustice faced by First Peoples in Victoria. This includes in relation to the child protection and criminal justice systems. The Commission will make bold recommendations for transformational change, including to support Victoria’s Treaty-making process.

Our priorities for the future

The final stage of Ending family violence: Victoria's 10-year plan for change implementation has five areas of focus. Each with its own set of priorities.

We will set out how we will deliver these priorities in the third and final Rolling Action Plan 2024-2026 under the 10-year plan. This plan will be released in 2024.

Drive down family and sexual violence

To achieve our vision of ending family and sexual violence, we need to stop people using violence and abuse in the first place.

Focus on children and young people

Children and young people are still developing their identities, values and behaviours.

Strengthen support for victim survivors

All Victorians should be able to get the support they need. It should be accessible, inclusive, culturally safe and tailored to their individual needs.

Respond to change

Our work to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence must not become stuck in a particular moment in time.

Understand and demonstrate our impact

Improving how we prevent and respond to family violence is not enough. We need to be confident our approach is working and understand why it is working.

Drive down family and sexual violence

The best way to change attitudes, beliefs and behaviours is to use the same messages in different settings – where people live, work, learn and socialise, including online.

To achieve our vision of ending family and sexual violence, we need to stop people using violence and abuse in the first place.

This means challenging deeply held attitudes, beliefs and gender stereotypes. It also means changing systems and structures that discriminate and enable this violence.

This is what we mean by primary prevention. It is complex, long-term work that requires all parts of our community to work together.

The latest evidence shows that Australians now understand more about violence against women and gender inequality. Their attitudes about this violence and inequality are also improving [1]. But progress is slow. Attitudes, beliefs and stereotypes are not shifting easily [1].

- 41 per cent of Australians believe that domestic violence is equally committed by men and women [1]. Yet it is mostly men who use violence, regardless of the gender of the victim [2].

- One-third of Australians believe that it is common for sexual assault accusations to be used as a way of getting back at men. This is not what the evidence tells us [1].

Build a community-wide approach to preventing family and sexual violence

The best way to change attitudes, beliefs and behaviours is to use the same messages in different settings – where people live, work, learn and socialise, including online.

This requires coordinated messages and activities that are reinforced in many different places at the same time. These messages and activities need to be tailored, accessible and engaging for people of different ages, identities, abilities, perspectives and backgrounds.

We will continue our nation-leading work to advance gender equality. This includes changing systems, structures, policies and laws that enable gender inequality and other forms of discrimination, such as racism, ageism and homophobia to continue. This will help achieve large-scale, long-lasting change.

Many organisations already work to prevent violence. They include local councils, early childhood services, schools, universities, TAFEs, health and sports organisations, sports clubs and groups from diverse communities. We now need to embed these efforts and connect this work to make change happen faster.

Support Aboriginal-led prevention

Aboriginal women, communities and organisations have a long history working to prevent family violence. They know the prevention activities that will be best for their communities.

Violence against Aboriginal people is connected to the ongoing effects of colonisation, dispossession, child removal and trauma that have been passed on through generations. Aboriginal people also experience racism and discrimination in the community and in the way systems, structures and government policies operate.

This is why we need a long-term, community-wide approach to preventing violence against Aboriginal women and children. Aboriginal people and organisations need to lead this work and we will support and partner with them in this. This includes transferring power and resources to them through the Treaty process and beyond.

Aboriginal children and young people need access to Aboriginal-led education initiatives that target the specific drivers of violence against them. We also need to improve early intervention for Aboriginal men who are at risk of using violence. These programs need to be holistic and culturally relevant.

We need to partner with Aboriginal communities to make sure the broader work we do to prevent violence across the community is culturally safe and appropriate.

Engage men and boys to change attitudes and behaviours that can lead to violence

Most violence perpetrated against people of any gender is committed by men [3]. We need to change men’s behaviour if we are to stop family and sexual violence. This means challenging harmful ideas about masculinity that are associated with violence. These ideas connect masculinity with dominance, control and aggression [4].

Men need to be part of the solution. They need to become allies in this work. Ending family and sexual violence is everyone’s responsibility.

We must challenge these ideas at critical development stages. This includes engaging with young men and boys as they are developing their identity, values and patterns of behaviour.

Boys and young men who develop positive ideas about masculinity are more likely to have respectful and healthy relationships free from violence.

References

[1] ANROWS (Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety) 2023, Attitudes matter: the 2021 National Community Attitudes Towards Violence Against Women Survey, accessed 13 June 2023.

[2] State of Victoria 2021c, MARAM practice guides: foundation knowledge guide – about family violence, accessed 8 June 2023.

[3] Our Watch 2019, Men in focus: summary of evidence in review, accessed 7 June 2023.

[4] Safe and Equal 2020, Rigid gender roles and stereotypes, accessed 22 June 2023.

Focus on children and young people

People who use violence against or in front of children and young people cause lifelong harm.

Children and young people are still developing their identities, values and behaviours. The experiences they have during this time can have a profound, long-term effect on their lives. If they experience family violence during childhood, it can have a big effect on their developmental, social and emotional wellbeing. However, if we support them to develop healthy and respectful relationships, they can become agents of generational change.

People who use violence against or in front of children and young people cause lifelong harm.

Children and young people who experience this violence have an increased risk of social, physical and mental health challenges. This includes anxiety and depression, self-harm and suicide, dependence on alcohol and drugs [1], disengagement from education, physical injury and disability [2].

They have unique and specific needs that are different from adults [2]. However, they may not be treated as a victim survivor in their own right.

Too often, they are seen as an extension of a parent seeking help. They may feel vulnerable and unsupported by services. Accommodation may not cater to their needs [3].

- 7,486 children and young people under the age of 18 were victims of family violence in 2022 [4]

- 36% of recorded family violence incidents occurred in front of a child or young person in 2022 [4]

- 10% of cases of child abuse in 2018–19 included sexual violence as the primary type of abuse [5]

- 48% of all assault-related hospitalisations of children were perpetrated by the child’s parent [3]

Engage children and young people to create generational change

By engaging children and young people in their formative years, we can challenge harmful attitudes before they become entrenched.

We know that rigid gender norms, stereotypes and other forms of inequality influence children. These continue to be reinforced throughout their lives [6].

We will continue to support schools and early childhood settings to provide respectful relationships education. This promotes and models respect, positive attitudes and behaviours, and teaches school communities how to build healthy relationships, resilience and confidence.

Beyond the classroom, we will continue our work to prevent family and sexual violence in the places where children and young people interact, including online. This will help them to develop healthy attitudes and respectful relationships.

In particular, we must continue our tailored prevention and early intervention projects that work with children and young people at heightened risk of experiencing or using family or sexual violence.

Provide support for children and young people where, when and how they need it

Children and young people need to feel a sense of agency about when and how they decide to seek help [7]. They should be able to make informed choices about getting support alongside or separately from family members.

Spaces and services that children and young people use should be designed with their specific needs in mind. This means using language that is accessible for children and young people [2]. It also means giving them opportunities to seek help and communicate through the technology and platforms they regularly use.

We must tailor support to the stage of development and unique needs of each individual child and young person. This includes children and young people of all genders, abilities and cultural backgrounds and faiths, and LGBTIQ+ young people in every part of Victoria.

In particular, young people aged 15 to 19 must not be lost in the gap between child and adult services [8].

We need to better understand the journeys of children and young people through the family violence system, from their first point of contact to their recovery. This will highlight what is working well and what is not, to help strengthen how we support them.

We must better connect family violence services, sexual violence services, children and family services, and specific services for young people. This will help these services work together with a shared focus on the child or young person seeking support.

Enable Aboriginal-led services for Aboriginal children and young people

Like all children, Aboriginal children and young people have the right to feel safe, heal and have a future free from violence. However, the ongoing effects of colonisation increase the risk of violence towards them and compound the trauma when they experience violence [9].

Family violence is one of the leading reasons Aboriginal children are removed from their family and placed into out-of-home care [10]. This means culturally safe initiatives to prevent and respond to family violence are vital to keeping Aboriginal children safe with their family.

We need to support Aboriginal children and young people to understand their rights and recognise violent or controlling behaviours. We need to address risks in families earlier. This work must be informed and led by Aboriginal people and organisations.

When Aboriginal children and young people do experience violence, we must support them to feel safe and heal. This healing should incorporate a strong sense of cultural identity, family and community.

This is why Aboriginal-led services must be funded and supported as the primary providers of healing and family violence services for Aboriginal children and young people.

At the same time, it is important that we make all family violence services culturally safe for Aboriginal children. This will help Aboriginal children and young people make informed choices about how and where they seek help.

Support children and young people who use violence to heal and change their behaviour

Most children and young people who use violence have experienced family violence themselves. In fact, 9 out of 10 adolescents who use violence at home say they have seen or experienced family violence [6].

This means that supporting children and young people to heal from their own trauma is a critical part of working with them to change their behaviour.

When our justice system interacts with these children and young people it must do so in a way that is trauma-informed. It needs to help them access services and support that are tailored to their individual needs, circumstances and stage of development. The focus of these services and support should be to address the root causes of their behaviour. This will help them to have healthy, supportive and violence-free relationships.

Currently, each area of the state has a dedicated program for these children and young people aged 12–17 years. However, there is high demand for this program, including for children as young as eight and young people up to the age of 25.

To move forward, we need to continue to listen to these children and young people. We need to provide them with meaningful opportunities to inform our decisions, act on their needs, and address their concerns and suggestions.

References

[1] ACMS (Australian Child Maltreatment Study) 2020, ACMS findings launched, accessed 26 June 2023.

[2] Fitz-Gibbon K, McGowan J and Stewart R 2023, I believe you: children and young people’s experiences of seeking help, securing help and navigating the family violence system. Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Monash University.

[3] AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2022b, Australia’s children: children and crime, accessed 8 June 2023.

[4] CSA (Crime Statistics Agency) 2022b, Victoria Police data tables (2021–2022): Table 4 Affected family members by sex and age July 2017 to June 2022, accessed 1 August 2023.

[5] AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2020, Sexual assault in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 7 June 2023.

[6] Fitz-Gibbon K, Meyer S, Boxall H, Maher J and Roberts S 2022, Adolescent family violence in Australia: a national study of prevalence, history of childhood victimisation and impacts, Research Report Issue 15, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety.

[7] Morris A, Humphreys C and Hegarty K 2020, ‘Beyond voice: conceptualizing children’s agency in domestic violence research through a dialogical lens’. International Journal of Qualitative Methods.

[8] Melbourne City Mission 2021, Amplify: turning up the volume on young people and family violence, research report, accessed 20 June 2023.

[9] Department of Health and Human Services 2018, Dhelk Dja: safe our way - strong culture, strong peoples, strong families, State of Victoria.

[10] CCYP (Commission for Children and Young People) 2016, Always was, always will be Koori children: systemic inquiry into services provided to Aboriginal children and young people in out-of-home care in Victoria, State Government of Victoria.

Strengthen support for victim survivors

All Victorians should be able to get the support they need. It should be accessible, inclusive, culturally safe and tailored to their individual needs.

The advocacy of victim survivors was pivotal in bringing about the Royal Commission into Family Violence, and they have been – and will continue to be – at the heart of our response.

We want victim survivors to be safe. We want them to have somewhere to live. They need access to justice, counselling, health care, education and employment.

More Victorians now know about family and sexual violence and how they can seek help. This means there is more demand for services and support that meet the unique and diverse needs of Victorians across their lifespan. We are building the size and capability of the workforce to meet this demand.

We have made rapid changes to the family violence system, which is made up of all the parts of government and all the community services that work to prevent and respond to family violence. Now, we need to deepen our understanding of how this system is working as a whole. Most importantly, we need to find out more about the experience of victim survivors as they journey through it.

Provide all Victorians who experience family or sexual violence with the support they need when they need it

All Victorians should be able to get the support they need. It should be accessible, inclusive, culturally safe and tailored to their individual needs. This includes the needs of Aboriginal people, children, young people, older people, people of every gender and LGBTIQ+ people. It includes people who are migrants, asylum seekers or refugees, people who speak a language other than English at home or are from diverse cultural backgrounds or faiths. It includes people with a disability and carers. It includes people living in rural or regional areas. It includes people working in the sex work industry. It includes people who have been imprisoned, convicted of a crime or have engaged with police because of illegal conduct.

When seeking help, it should not matter where someone lives or how they choose to seek help. Our diverse community should have diverse ways to get help. This ensures people can make the choice that is most comfortable for them. All entry points must lead to safety and timely, high-quality support.

We have still got work to do to achieve this vision, alongside the many organisations we partner with across Victoria and people with lived experience who use these services.

Continue to shift the focus onto people who use violence

Too often, people who use violence are not held accountable for their behaviour. They can continue their lives, while victim survivors have to make big changes to stay safe.

We must continue to shift the focus onto perpetrators.

Justice services, such as police and the courts, play a vital role in this. We need to continue to build a strong web across the justice system and family violence services that keeps perpetrators visible and accountable. As part of this web, Victoria Police will continue to seek consequences for perpetrators of family violence.

We will also continue to provide people who use violence with the right services, at the right time. Our aim is to help them change their behaviour over the long term. This is one of the best ways we can keep victim survivors safe. Sometimes, this includes providing emergency accommodation to people who use violence to reduce the risk to the safety of their family at home. We will also continue to improve their access to legal services. This can be a way to connect them with services that help them change their behaviour.

It is important that we understand how the risks posed by people who use violence can change over time. Sharing information about these risks across justice and family violence services will help us manage them together. This will give people who use violence the greatest chance to change their behaviour over the long-term.

We will also strengthen our ability to intervene early. This means identifying times of heightened risk or at the first indication that someone has used or experienced violence. The first time they engage with the criminal justice system can be a good time to do this. We know the risk of violence also increases when a person leaves their relationship, when they are pregnant and just after they give birth [1]. These are key moments when intervening early can have the greatest impact.

It is also important we keep working to make sure we correctly identify the person who is using violence in the family. Sometimes, victim survivors are misidentified as the perpetrator. This causes further harm to them. In particular, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are disproportionately misidentified as the perpetrator of violence.

People who use family and sexual violence are not all alike. We know the majority are men. However, we need more interventions across wider geographical areas. These interventions need to be tailored for the specific needs of LGBTIQ+ communities, multicultural and multifaith communities, people with disability, young people, older people, people who commit elder abuse, and women who use violence.

Support Aboriginal-led responses for Aboriginal victim survivors and people who use violence

Our response to family violence and sexual violence against Aboriginal people needs to be led by Aboriginal people. This includes for Aboriginal women, children, young people, men, Elders, older people, families and communities [2].

It needs to draw on their cultural knowledge, strengths and resilience. This is the best way to reduce the incidence and intergenerational impacts of family violence and sexual violence. We will do this when supporting the healing and safety of Aboriginal communities, as well as when working with Aboriginal people who use violence.

We will continue to support a strong Aboriginal community-controlled family violence sector to lead this work in partnership with government.

Equally, our mainstream organisations must be equipped to provide culturally safe support to Aboriginal victim survivors and Aboriginal people who use violence.

Increase the number of skilled and diverse workers to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence

Preventing and responding to family violence is challenging and complex work. It is also meaningful and rewarding. It helps to stop family violence from happening in the first place and makes a difference in the lives of those who have been harmed by violence.

We need more workers with the right skills to specialise in this work or contribute to it from sectors, such as health, education, justice and community services.

Workers should reflect the diversity of the communities they engage with. The specialist family and sexual violence sectors should become ‘industries of choice’ for graduates. To do this, we need to keep improving conditions for workers in these sectors.

Some organisations are finding it difficult to recruit and retain the vital workers they need. This is particularly critical for Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations which are working to increase the number of Aboriginal workers for Aboriginal-led and self-determined services. These services face particular challenges due to the continued impacts of colonisation and discrimination.

As more people experiencing or at risk of violence seek the help they need, the demand for family and sexual violence services in Victoria increases. This increases demand on frontline workers who are already experiencing high workloads due to a shortage of available staff. Some frontline workers are employed on short-term contracts. This can affect their job security. It can also contribute to turnover of staff.

We have introduced a minimum qualifications policy for new family violence response workers. This is helping us provide a consistent standard across our family violence services. It also recognises the specialised nature of this work. However, this policy is being implemented at a time when there are broader workforce shortages. This can make it difficult for employers to find workers.

Employers are continuing to trial ways to support people from diverse backgrounds and with different forms of expertise to gain the qualifications they need. We will also continue to monitor our minimum qualifications policy and, if needed, adjust it so that it achieves the intended outcomes.

We are helping organisations to recruit and retain the diverse workers they need. This includes boosting the leadership capability in the sector and strengthening support for worker health, wellbeing and safety. We recognise and value the lived experience of many of these workers.

References

[1] Campo M 2015, Domestic and family violence in pregnancy and early parenthood: overview and emerging interventions, Australian Institute of Family Studies.

[2] Department of Health and Human Services 2018, Dhelk Dja: safe our way - strong culture, strong peoples, strong families, State of Victoria.

Respond to change

Our work to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence must not become stuck in a particular moment in time.

Victoria has changed a lot since the Royal Commission into Family Violence handed down its recommendations in 2016. We have been through major fires, floods and a global pandemic. Technology has changed quickly, and this has changed how we engage with each other. International and Australian movements have prompted society-wide conversations about gender inequality and violence against women, which have made more people aware of this violence.

Our work to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence must not become stuck in a particular moment in time.

We need to respond to the cultural, social and technological shifts that are taking place around us. Our work must be resilient so it can withstand future crises.

Respond to cultural, social and technological shifts that impact family and sexual violence

Technology is increasingly influencing how Victorians initiate and conduct intimate relationships. It can also support violence in those relationships.

For example, online dating platforms create opportunities for meeting new partners, but they also create risks of violence. In a survey about abuse on online dating apps, three in four participants reported experiencing sexual harassment, violence and aggression from people on those apps. The rates are much higher for LGBTIQ+ people [1].

There are popular influencers who use online platforms to promote harmful ideas about masculinity. Some of these influencers directly advocate violence against women.

Widespread consumption of free, anonymous, accessible pornography through mobile devices provides two key challenges in the context of family and sexual violence.

The first is that children and young people are being exposed to harmful sexual content that is not appropriate for their stage of development – 44 per cent of young people aged 9–16 years have encountered sexual images [2]. In the absence of other information, pornography can be the main way that young people learn about sex. It can shape their sexual attitudes and behaviours.

Second, while not all pornography depicts harmful or violent behaviour, mainstream online pornography includes high levels of violence, hostility and sexist content [2]. This content is highly gendered. One study found that 97 per cent of physical aggression was targeted at women, while men were the perpetrators in 76 per cent of scenes [3].

When men use this type of pornography, they are more likely to use violent sexual behaviours, such as choking a sexual partner without their consent [4]. This is also reflected in accounts of sexual violence by victim survivors. A significant proportion of victim survivors in one study said, unprompted, that pornography use contributed to the violence against them [5].

We need to build our understanding of these trends and explore opportunities to address them. We will work with other states and territories, and where appropriate, digital companies themselves, so that the use of online platforms does not increase the risk of family and sexual violence.

There are also opportunities to provide more comprehensive sexual education to children and young people. This will help them engage more safely and critically with sexual content when they are exposed to it.

Respond to new forms of family and sexual violence

Perpetrators increasingly use technology as part of their violence. This includes surveillance, coercion, recording sexual violence, abusive messages, online sexual harassment and using technology to perpetrate other forms of harm such as financial abuse or humiliation [6]. Our laws and frontline services have not always kept pace with these changes. This makes it difficult to police, prosecute and respond when perpetrators use technology in their abuse.

We need to find out more about how we can prevent people from being monitored or harmed by family members or intimate partners while using technology. This includes helping Victorians to protect themselves online. We also need to help our systems and institutions to identify and respond to perpetrators’ use of technology.

- 99 per cent of family violence and sexual violence frontline workers have worked with clients who have experienced technology-facilitated violence [7].

- From 2015 to 2022, there was a 245 per cent increase in family violence workers reporting that perpetrators used GPS tracking on victim survivors. There was a 183.2 per cent increase in the use of video cameras to monitor victim survivors [7].

- One in 10 Australians has had someone share intimate or sexual photos or videos of them online without consent [8].

Embrace technology in how we prevent and respond to family violence

Changing technology creates new challenges, but it also gives us new ways to engage Victorians and influence attitudes and behaviours.

New communication platforms allow people to get information and support. We will continue to improve the way we use technology to communicate and provide information and resources.

We will also continue to use technology and online platforms to facilitate community conversations about family violence and violence against women. These conversations can help challenge harmful attitudes and encourage behaviour change.

Technology can transform the way we share information across systems and services. This means we can be more consistent in the way we work with both victim survivors and the people who use violence against them. It also means we can manage risk more effectively. We will focus on making better use of technology in the coming years.

Reduce and respond to the risk of family violence during times of crisis

Times of crisis and disaster can increase the risks of violence within a community. They can also disrupt support services [9].

We must prepare communities and key workers to respond to family violence during disasters. We must also provide targeted early intervention and prevention initiatives in high-risk communities to reduce the risk of violence increasing when disasters occur.

We also need to learn from previous crises so we can prepare for the future. This includes the way specialist family violence services rapidly adapted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

[1] Australian Institute of Criminology 2022, Sexual harassment, aggression and violence victimisation among mobile dating app and website users in Australia, AIC reports: research report 25.

[2] AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) 2017, Online pornography: effects on children and young people, research snapshot, accessed 20 June 2023.

[3] Fritz N, Malic V, Paul B et al. 2020, ‘A descriptive analysis of the types, targets, and relative frequency of aggression in mainstream pornography’. Arch Sex Behav, vol. 49, pp. 3041–3053.

[4] Wright PJ, Herbenick D and Tokunaga RS 2023, ‘Pornography consumption and sexual choking: an evaluation of theoretical mechanisms’, Health Communication, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 1099–1110.

[5] Tarzia L and Tyler M 2021, ‘Recognizing connections between intimate partner sexual violence and pornography’, Violence Against Women, vol. 27, no. 14, pp. 2687–2708.

[6] Harris B 2020, Technology, domestic and family violence perpetration, experiences and responses, Centre for Justice Briefing Paper, no. 4, Queensland University of Technology.

[7] Woodlock D, Bentley K, Schulze D, Mahoney N, Chung D and Pracilio A 2020, Second national survey of technology abuse and domestic violence in Australia. WESNET.

[8]Office of the eSafety Commissioner 2017, Image-based abuse: national survey summary report, Australian Government.

[9] AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) 2010, Picking up the pieces, Family Matters no. 84, accessed 22 June 2023.

Understand and demonstrate our impact

The information we collect, and how we analyse it, shapes our understanding of how change is happening.

Improving how we prevent and respond to family violence is not enough. We need to be confident our approach is working and understand why it is working. This is so we can be sure that our actions improve peoples’ lives and lead to the outcomes we are working towards.

Strengthen how we measure impact

The information we collect, and how we analyse it, shapes our understanding of how change is happening. We need to know we are asking the right questions at the right time to be able to evaluate our progress.

Family violence, sexual violence and violence against women are complex social problems. We must build our knowledge of how the community understands and thinks about these forms of violence. This includes the underlying attitudes, beliefs and behaviours that support it. Changing these attitudes, beliefs and behaviours will take time. We need to know the short and medium-term milestones that will tell us we are moving in the right direction.

Government, peak organisations, data custodians and service providers each have a role to play in building strong, reliable data and evidence in Victoria. Organisations that work to prevent and respond to family and sexual violence play a key role. They gather and share information about the effect their work has. They need to be equipped to collect, analyse and use this data. We need to strengthen their capacity to provide this information in a way that adds value to their work. Importantly, we do not want to create an additional administrative burden.

We will also focus on improving how we collect and use data about the intersecting factors that increase the risk of violence and barriers to seeking help.

Linking this data in better ways will help us see the full picture. It will help us identify what is working and what is not. It will allow us to regularly analyse the journeys of victim survivors, including children and young people, as well as people who use violence, through the service system.

Increase opportunities for Victorians to help us improve the system

People who have experienced family and sexual violence know best whether our system is giving them the support that they need. We will continue to welcome and seek out the expertise of victim survivors at every level of our work – from designing policies and programs through to delivering them and evaluating their impact.

We will strengthen our engagement with people who use violence to learn more about the interventions that have the best chance to change their behaviour.

We know that both the risks and effects of family violence can differ greatly across our society, so we will continue to work with Victorians from diverse backgrounds and identities when we design our programs and monitor their success.