- Published by:

- Department of Education

- Date:

- 28 Aug 2024

The Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) is subject to an independent review of its operation within 2 and 5 years of commencement under sections 41ZN and 41ZO of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005.

The 2-year review took place in 2020, covering the period from September 2018 to September 2020. For more information, see Child Information Sharing Scheme Reviews.

The 5-year review covers the period from September 2018 to September 2023. It considers two key review questions:

- to what extent has the operation of CISS achieved its intended reform outcomes to date?

- do the findings from the review support any considerations for changes to the legislative and/or regulatory settings of the reform?

Government response

The Victorian Government has provided a response to the recommendations of the 5-year review.

Key Insights

The Victorian Child Information Sharing (VCIS) Reform – including the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) – is a broad and ambitious reform affecting the entire ecosystem of services that relate to children and families in Victoria. In policy, planning, implementation and practice it should be understood as extending beyond government and encompassing the whole community.

Implementation has been effective and collaborative

- CISS implementation is an example of a number of Victorian Government departments and agencies working collaboratively and effectively to introduce a significant reform.

- Implementation has generally been effective to this point in the scheduled rollout of Phase One (September 2018) and Phase Two (April 2021).

There are positive signs towards achieving medium-term outcomes relating to cultural change towards information sharing

- There is high awareness of CISS. Understanding of CISS is higher among Phase One Information Sharing Entities (ISEs) as would be expected.

- There has been significant progress in willingness to share information and in realising cultural change of attitudes towards information sharing. This is especially pronounced in Phase One workforces and in the education (Phase Two) sector.

Although awareness of CISS has grown, there is not a complete picture of ISE familiarity

- A large amount of training, support services and communication effort has occurred, reaching thousands of individuals and ISEs. However, there is no register of who has completed CISS training across ISEs and/or whether an ISE has an appropriately trained individual member(s) on staff at any given time.

There is an opportunity to improve understanding of Scheme activity

- Recording of information sharing is designed to only occur at an ISE level. Consequently, there is no comprehensive single source of truth regarding overall Scheme use by different ISEs and workforces, making it difficult to assess growth in information sharing over time.

More needs to be done to enable assessment of CISS’ impact

- The Department is progressively implementing an outcome measurement framework for CISS. While there is an opportunity to track CISS’ impact on child wellbeing and safety, the current data collection approach does not enable this to meaningfully occur.

- While this Review considered implementation and understanding of CISS among ISEs and government stakeholders, including feedback about CISS’ operation, there are information gaps regarding CISS’ overall effectiveness.

There are potential risks inherent in aspects of CISS currently

- Reporting of misuse of information is the responsibility of ISEs. While this Review did not uncover specific incidents of information being misused, it received qualitative reports of instances of ISEs inadvertently sharing an unnecessary amount of information. Some stakeholders were concerned about the level of understanding regarding what may and may not be shared in different circumstances.

- While the Department and partner agencies have sought to ensure safeguards within CISS for Aboriginal cultural safety through the legislative framework and guidelines, CISS’ decentralised oversight model incurs a risk that could lead to unintended consequences for some vulnerable groups if these guidelines are not followed.

- Some workforces that hold information relating to the wellbeing and safety of children were not included in Phase One or Phase Two, including disability services that are not delivered within registered community health services, and private mental health services or those that are not Commonwealth-funded. Adjacent jurisdictions are also not included. These exclusions can reduce the comprehensiveness of information available in certain circumstances.

Opportunities

This Review recommends that these aspects of CISS’ oversight and community engagement be refined:

- Scheme oversight can be improved through expanding the Outcome Measurement Framework to include ongoing monitoring of the Scheme’s utilisation. This will allow better understanding of Scheme outcomes, a clearer process for complaints and ensuring ISEs understand their obligations.

- Communities can be empowered to make decisions within the CISS guidelines by expanding the place-based approach to Scheme education and communication and recognising non-government organisations in advising on CISS. A specific program of work partnering with Aboriginal leaders, communities, organisations and stakeholders is needed, recognising Victoria’s commitment to self-determination and building confidence in the use of CISS. More work is required to understand the impact of CISS on diverse communities and Victorians experiencing vulnerability.

- A further phase of rollout would be strengthened through implementation of these improvements, along with continuation of the enquiry line and inclusion of other jurisdictions subject to required agreement(s) being reached.

Executive Summary

The Child Information Sharing Scheme

Multiple independent reviews and inquiries have been conducted into child wellbeing and safety in Victoria since 2011.1 A common theme to emerge from those reviews was that a lack of information sharing was a significant barrier to effective and timely support for families and children.2 Overall, there was found to be a risk-averse culture to information sharing created by the complexity of multiple legislative frameworks, including the Children Youth and Families Act 2005,3 Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 and the Health Records Act 2001.4,5,6 The Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) was established in September 2018 under Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (the Act) in response to these reviews. CISS was designed to enable prescribed Information Sharing Entities (ISEs) to share confidential information in a timely and effective manner to promote the wellbeing and safety of children.

CISS aims to facilitate the early identification, assessment and management of child wellbeing and safety through inter-service collaboration across a range of contexts, and operates alongside other information sharing schemes such as the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS)7 and digital tools such as the Child Link Register (Child Link). The Victorian Department of Education (the Department) leads the implementation of CISS, and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing leads the implementation of FVISS, and implementation has been coordinated across these reforms and the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Framework (MARAM). The coordination in reform delivery is in recognition of the significant overlap between the workforces and organisations prescribed under the schemes and that child wellbeing and safety concerns can be observed at multiple touchpoints across distributed service systems and in a variety of situations in which the schemes may be applied.8

There is a total of 8,269 prescribed ISEs under CISS, with approximately 700 entities prescribed in Phase One (September 2018, primarily Victorian Government agencies such as secondary and tertiary services overseen by the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, the Department of Justice and Community Safety, and Victoria Police) and approximately 7,500 prescribed in Phase Two (April 2021, primarily universal services overseen by the Department of Education and the Department of Health).

This Review

Under Section 41ZN and 41ZO of the Act, CISS is subject to an independent review of its operation within two and five years of commencement. The Two-Year Review of CISS (the Two-Year Review) took place in 2020, covering the period from September 2018 to September 2020.

This Five-Year Review (this Review) covers the period from September 2018 to September 2023. This Review considers two key review questions:

- to what extent has the operation of CISS achieved its intended reform outcomes to date?

- do the findings from the review support any considerations for changes to the legislative and/or regulatory settings of the reform?

To support responding to these two key questions, nine sub-review questions were developed (see Sub-review questions of the Five-Year Review below), organised into the three domains of implementation, effectiveness and legislative and regulatory settings. The evidence and findings in this report are structured in response to these review questions, as well as to the outcomes in the VCIS Reform Program Logic Model (the Program Logic), detailed at Appendix A.

A mixed-methods approach was adopted to obtain the relevant data and information to respond to the review questions. The detailed methodology is included at Appendix B.

As detailed at Appendix C, the CISS Workforce Survey was distributed to and completed largely by public sector staff and agencies involved in CISS activity. The consultations were held across government and non-government stakeholders, including representation from small ISEs.

Sub-review questions of the Five-Year Review

Review Domain 1: Implementation

- Is CISS being implemented within its scope as defined by Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005?

- What have been the key enablers and barriers to implementation?

Review Domain 2: Effectiveness

- To what extent has CISS achieved its intended outcomes to date? How close is CISS to achieving its medium-term (5-year) outcomes and are there early indicators of CISS achieving its long-term (10- year) outcomes?

- Is there any evidence of negative impact of CISS on diverse communities and communities experiencing disadvantage?

- Are there any unintended consequences of implementation – both positive and negative?

Review Domain 3: Legislative and regulatory impact and settings

- Are there any unintended consequences of interpretation – both positive and negative?

- Do the findings of this review support any considerations for changes to the legislative settings of CISS?

- What are the impacts of the current Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018 and what are the issues related to the Regulations (if any)?

- What could be done to address the issues, if any, related to the Regulations? When answering this, consider both Regulatory amendment and non-Regulatory options.

Key findings

Recommendations

This Review makes the following recommendations grouped into three categories: CISS oversight, community empowerment, and growth opportunities. It should be noted that the recommendations would require resourcing during the implementation phase and some may impose an ongoing regulatory burden or cost on some stakeholders relative to the current arrangements. However, where this is the case, it is because the review has formed a view regarding the adequacy of certain aspects of CISS’ design and operation. It would consequently be advisable for the anticipated benefits and costs of the recommendations to be assessed prior to their implementation, particularly where the change suggested is relatively significant. Equally the inherent difficulty in foreseeing and measuring all costs and benefits relating to information sharing is acknowledged. This uncertainty should not be cited as a barrier to reasonable and proportionate strengthening of CISS, which is the overall intent of these recommendations.

CISS oversight

Summary: Recommendations regarding CISS oversight are built around the identified need to create greater understanding and visibility of CISS’ usage at a departmental level and embed greater accountability and awareness of obligations at the ISE level. These recommendations taken together seek to strengthen the degree to which CISS is able to deliver on its intent and minimise the risks of misuse.

Recommendation 1

Establish a mechanism to capture data that enables an accurate picture of the use of CISS to be developed over time.

Recommendation 2

Prioritise the continued improvement and full rollout of the Outcome Measurement Framework including an accompanying data collection and analysis approach that will improve understanding of the impact of CISS on child wellbeing and safety, which will in turn guide CISS improvement.

Recommendation 3

Ensure every ISE has appropriate representative(s) who have undertaken up-to-date CISS training.

Recommendation 4

ISEs maintain a CISS training register to ensure information about trained individuals is available to the Department upon request.

Recommendation 5

Strengthen support available to ISEs through implementation activities such as training (mandatory/refresher), support services and communication to ensure all ISEs understand their obligations to report potential breaches of the Act and/or misuse of information.

Recommendation 6

Clarify the CISS complaints process for ISEs wishing to raise concerns or make complaints about non-privacy related matters.

Community empowerment

Summary: Recommendations regarding community empowerment are built around the identified need to embed CISS practices more deeply across all sectors, workforces and communities prescribed under CISS. These recommendations are designed to support a greater understanding at the departmental level of the diverse ecosystems within which decisions around the CISS must be made by ISEs, and to provide pathways for the co-creation of targeted programs of work and materials that will instil confidence and agency across communities in their use of CISS.

Recommendation 7

Adopt a place-based approach to change management and supporting ISEs with meeting their CISS obligations and opportunities for information sharing, including providing support to ACCOs and services directly from the Department of Education and partner agencies.

Recommendation 8

To ensure that CISS is embedded to benefit Aboriginal children and their families, the Department should collaborate with Victorian Aboriginal communities to inform how the principles of Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Data Governance can be embedded and understood through CISS, enabling ACCOs and communities to make self-determining decisions about their data.

Recommendation 9

Develop a program of work (as a monitoring activity within the Outcome Measurement Framework) to better understand the impact of CISS on diverse communities and communities experiencing disadvantage including how any positive impacts of information sharing can be enhanced with any unintended consequences identified.

Recommendation 10

Improve ISE confidence and capability in engaging with children and their parents or carers about the benefits of information being shared to promote the wellbeing and safety of children.

Recommendation 11

Include non-government organisations in the CISS governance model, recognising that CISS is designed to extend well beyond Victorian Government entities in its scope.

Growth opportunities

Summary: Recommendations regarding growth opportunities are built around the identified need to facilitate the sharing of information between professionals to promote child wellbeing and safety wherever and with whomever that information is held, beyond the current scope of prescribed ISEs. These recommendations respond to gaps in the current Regulations as they relate to the exclusion of workforces and organisations, recognises the intersection and interaction of different legislative and regulatory systems in the State, as well as jurisdictional challenges that will require collaboration with governments outside of the state of Victoria. While expansion of CISS may be appropriate, the precise scope of any proposed expansion needs to be determined and expansion should only proceed with agreement of the CISS partner agencies.

Recommendation 12

Work with other governments (particularly New South Wales, South Australia and the Commonwealth) to enhance information sharing, particularly to promote child wellbeing and safety in border communities.

Recommendation 13

Determine the appropriate scope of further CISS expansion to remaining sectors that have high involvement with children and families.

Recommendation 14

Consider implementing the improvement opportunities identified by the above recommendations, to further strengthen CISS and support any expansion of ISEs.

Notes

1 These reviews and inquiries were identified by the Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines – Guidance for information sharing entities to include: Commission for Children and Young People 2014–15 Annual Report; Commission for Children and Young People 2015–16 Annual Report; Commission for Children and Young People 2016–17 Annual Report; Commission for Children and Young People 2016, Neither seen nor heard: Inquiry into issues of family violence in child deaths; Coroner Court of Victoria, 2015, Inquest into the Death of Baby D; Cummins, et al 2012, Report on the Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry; Department of Health and Human Services 2016; Royal Commission into Family Violence, 2016, Report and recommendations; Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, 2011, Early Childhood Development Services: Access and Quality; Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, 2015, Early Intervention Services for Vulnerable Children and Families; Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017.

2 Regulatory Impact Statement: Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018.

3 Victorian Government, Children, Youth and Families Act (2005)

4 Victorian Government, Privacy and Data Protection Act (2014)

5 Victorian Government, Health Records Act (2001)

6 Ibid.

7 The FVISS supports the sharing of information to assess the risk of family members from family violence (including adult and children victim survivors).

8 Regulatory Impact Statement: Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018.

9 The total size of the CISS workforces is estimated to be approximately 265,000 professionals.

The Child Information Sharing Scheme

1.1 Background

Multiple independent reviews and inquiries were conducted into child wellbeing and safety in Victoria since 2011. These include:10

- Protecting Victoria’s Vulnerable Children Inquiry, 2012

- Victorian Auditor-General’s Office reports into vulnerable children and families

- Early Childhood Development Services: Access and Quality, 2011

- Early Intervention Services for Vulnerable Children and Families, 2015

- Coroners Court of Victoria, Inquest into the Death of Baby D, 2015

- Commission for Children and Young People Child Death Inquiries, 2014-17

- Commission for Children and Young People Inquiry into issues of family violence in child deaths, 2016

- Royal Commission into Family Violence, 2016

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017.

These independent reviews and inquiries highlighted a lack of sharing of critical confidential information between state-funded service provider entities. This lack of information sharing was identified as a significant barrier to effective and timely support for children and families experiencing vulnerability, with service providers unable to coordinate and collaborate effectively. In Victoria, the Royal Commission into Family Violence (2016) identified significant barriers to effective information sharing among entities involved in family violence cases, including concerns about privacy, confidentiality, legal constraints and a lack of coordination among various agencies and service providers. The fragmented and uncoordinated approach to sharing of information was noted to particularly hinder comprehensive risk assessment cases involving children, making it difficult to identify and manage risks effectively and in a timely manner. The Royal Commission into Family Violence (2016) emphasised the need for clear and consistent information sharing protocols and procedures and recommended the creation of a central information point.

At a national level, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017) emphasised the need for improved information sharing and recommended the establishment of a national information exchange scheme, with nationally consistent legislative and administrative information sharing arrangements in each Australian jurisdiction. It also stressed the importance of education, training and guidelines to promote the understanding of, and confidence in, information sharing arrangements among key entities. Based on its findings, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017) made recommendations to address these barriers to information sharing. These are summarised in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Recommendations from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017) that relate to information sharing schemes

Recommendation 8.6

The Australian Government and state and territory governments should make nationally consistent legislative and administrative arrangements, in each jurisdiction, for a specified range of bodies (prescribed bodies) to share information related to the safety and wellbeing of children, including information relevant to child sexual abuse in institutional contexts (relevant information). These arrangements should be made to establish an information exchange scheme to operate in and across Australian jurisdictions.

Recommendation 8.7

In establishing the information exchange scheme, the Australian Government and state and territory governments should develop a minimum of nationally consistent provisions to:

- enable direct exchange of relevant information between a range of prescribed bodies, including service providers, government and non-government agencies, law enforcement agencies, and regulatory and oversight bodies, which have responsibilities related to children’s safety and wellbeing

- permit prescribed bodies to provide relevant information to other prescribed bodies without a request, for purposes related to preventing, identifying and responding to child sexual abuse in institutional contexts

- require prescribed bodies to share relevant information on request from other prescribed bodies, for purposes related to preventing, identifying and responding to child sexual abuse in institutional contexts, subject to limited exceptions

- explicitly prioritise children’s safety and wellbeing and override laws that might otherwise prohibit or restrict disclosure of information to prevent, identify and respond to child sexual abuse in institutional contexts

- provide safeguards and other measures for oversight and accountability to prevent unauthorised sharing and improper use of information obtained under the information exchange scheme

- require prescribed bodies to provide adversely affected persons with an opportunity to respond to untested or unsubstantiated allegations, where such information is received under the information exchange scheme, prior to taking adverse action against such persons, except where to do so could place another person at risk of harm.

Recommendation 8.8

The Australian Government, state and territory governments and prescribed bodies should work together to ensure that the implementation of our recommended information exchange scheme is supported with education, training and guidelines. Education, training and guidelines should promote understanding of, and confidence in, appropriate information sharing to better prevent, identify and respond to child sexual abuse in institutional contexts, including by addressing:

- impediments to information sharing due to limited understanding of applicable laws

- unauthorised sharing and improper use of information.

Source: Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017).

These reviews consistently highlighted the detrimental impact of inadequate information sharing on the wellbeing and safety of children, and identified the need for simplified information sharing arrangements which promote a shared responsibility among service entities to improve outcomes for children. Recurring overarching themes highlighted by these reviews included:

- Victoria’s legislative framework was complex and had contributed to the creation of a risk-averse culture which hindered the effective sharing of information

- entities were unable to form a holistic understanding of a child’s circumstances and participation in services, which risked delays in timely intervention.

Subsequent to the establishment of CISS, the Commissioner for Children and Young People conducted the ‘Lost, not forgotten’ (2019) inquiry into children and young people who died by suicide and were known to Child Protection between 1 April 2007 and 1 April 2019. The inquiry report found that there was inadequate information sharing and collaborative practices among services in these cases.

1.1.2 Victorian Child Information Sharing Reform

In response to the findings and recommendations of these reviews, the Department led a program of policy work and undertook extensive consultation with relevant stakeholders, including (but not limited to) those from the following sectors: health, community services, family violence, ACCOs and unions.

The policy work undertaken by the Department led to the establishment of the Children Legislation Amendment (Information Sharing) Act 2018, which inserted Parts 6A and 7A into the Act, which established CISS and enabled the establishment of Child Link, collectively referred to as the VCIS Reform.

The Victorian Child Information Sharing and Early Childhood Systems Division (VCISECS) is the team within the Department that is responsible for implementing the VCIS Reform.

The purpose of the VCIS Reform, as noted in the Second Reading Speech, was to:

“…propose a new approach to child information sharing… that will boost [Victoria’s] capacity for early intervention and prevention. [The VCIS Reform] will elevate Victoria's already strong commitment to promoting child and family centred service collaboration and shared responsibility for the wellbeing and safety of our children to new levels.” 11

The objective of the VCIS Reform is to promote better child wellbeing and safety outcomes by enabling specified government agencies and service providers to share information that will:

- improve early risk identification and intervention

- change a risk averse culture in relation to information sharing

- increase collaboration and integration between child and family services

- support children’s participation in services.

Given the significance and complexity of CISS, provisions were inserted into the Act mandating a two- and a five-year independent review to assess the operation and any adverse impacts of CISS.

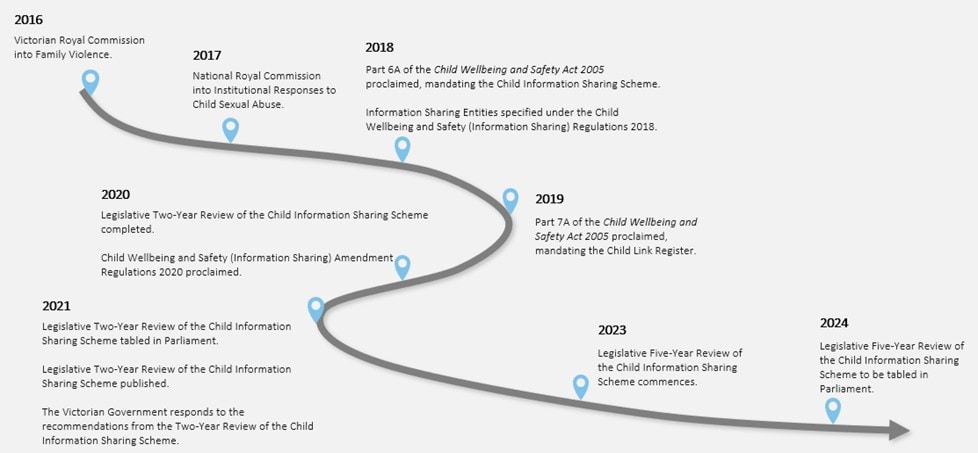

1.1.3 VCIS Reform timeline

Figure 1.2 provides an overview of the key milestones in the establishment and implementation of the VCIS Reform which are discussed throughout this report.

1.2 Policy context

1.2.1 Information sharing legislation existing prior to the Child Information Sharing Scheme

Prior to the establishment of CISS, Victoria’s legislative framework for information sharing in relation to children experiencing vulnerability was complex, with several overlapping Acts such as the Children Youth and Families Act 2005,12 Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 and the Health Records Act 2001.13, 14 This legislation has supported the development of safe practices around information sharing for entities to best support families and protect children.

However, Commonwealth privacy laws and various confidentiality provisions under subject-specific pieces of Victorian legislation created confusion for entities about when and what information may lawfully be shared. Due to the complexity of the legislative environment, entities were required to understand and apply different legal standards to determine whether information could be shared in a particular circumstance and lacked confidence in their ability to do so. Historically, this had led to entities developing a risk-averse culture where information was not commonly shared, even when legally permitted and appropriate. Where critical information relevant to a child’s wellbeing and safety is not shared in a timely manner, opportunities for early intervention or prevention are often missed. These missed opportunities to prevent issues escalating to a crisis point, can lead to severe adverse outcomes for children, and an over-reliance on costlier child protection services.

Furthermore, there was no legislative provision which specifically authorised information sharing to promote child wellbeing and safety, with the legislative framework being narrowly focused on care and protection.

While the pre-existing legislation remains current, CISS was established to overcome these barriers by clarifying and expanding the circumstances in which entities can share information relating to the wellbeing or safety of children.

1.2.2 Roadmap for Reform

Building on the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Family Violence, the Victorian Government released the Roadmap for Reform: Strong Families, Safe Children (the Roadmap) in 2016.15 The Roadmap stepped out immediate actions to focus on early intervention and prevention, and enhance the child protection system, to better support the wellbeing and safety of children and families.

Information sharing was identified in the Roadmap as a key enabler for achieving reform objectives, encouraging collaboration and coordination and supporting a multi-agency approach to the identification of risk factors.

The actions in the Roadmap complement other Victorian reforms aimed at improving accessibility of universal services, such as the Education State reforms, targeted at developing a quality education system that is available to all students (including, for example, the Education State Early Childhood Reform Plan)16, and Victoria’s 10-Year Mental Health Plan.17

1.2.3 Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme and Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management

CISS operates alongside FVISS, which was incorporated into the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 in 2018. Both schemes facilitate information sharing among prescribed entities, with FVISS allowing the sharing of information to assess and manage family violence risks to both children and adults. The MARAM Framework sets out the responsibilities of different workforces in identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk across the service system, seeking to guide information sharing schemes wherever family violence is present.

As the information shared under FVISS may also be relevant to child protection and wellbeing, the application of both FVISS and CISS overlap in some circumstances for certain children and families.

1.2.4 Funding

The VCIS Reform has received funding allocations in Victorian State Budgets since its establishment, including:

- $42.9 million over four years in implementation funding in the 2018-19 Budget

- $97 million over four years in training and skills development across CISS, FVISS and MARAM in the 2021-22 Budget.

1.3 Child Information Sharing legislative framework

1.3.1 Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005

1.3.1.1 Child Information Sharing Scheme

Part 6A of the Act authorises prescribed organisations and services, defined as ISEs, to both request and disclose confidential information (either voluntarily or in response to a request) to another ISE for the purpose of promoting the wellbeing or safety of children.

In recognition that the disclosure of confidential information will not be appropriate in all circumstances, the Act excludes information from CISS under a number of prescribed circumstances, such as if the disclosure of the information could endanger a person’s life, result in physical injury or prejudice an investigation, a coronial inquest or inquiry, or a criminal or civil trial.

A number of principles intended to guide the collection, use or disclosure of information are set out in the Act. These principles include that ISEs should:

- prioritise the wellbeing and safety of children over privacy concerns

- only share information to the extent necessary to promote the wellbeing or safety of children

- encourage collaborative and respectful work between ISEs

- involve children and their families where appropriate and safe

- emphasise positive family relationships and cultural identities

- plan for the safety of all family members at risk from family violence

- promote cultural safety and recognise cultural rights and connections of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children

- seek to maintain constructive and respectful engagement with children and their families.

1.3.1.2 Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines

To support appropriate information sharing practices, Section 41ZA of the Act requires the Minister to issue guidelines which detail how ISEs should responsibly handle confidential information under CISS, as well as set out how the legislative principles outlined in the Act (see Section 1.3.1.1) are to be applied by ISEs.

The Ministerial Guidelines provide detailed guidance about the circumstances in which information can be shared between ISEs,18 including a three-part threshold that must be met in order to share confidential information under CISS:

- the purpose of sharing the confidential information is to promote the wellbeing or safety of children

- the disclosing ISE reasonably believes that sharing the information will assist the receiving ISE in conducting activities such as making decisions, assessments or plan related to children, initiating or conducting investigations, providing services or managing risks for children

- the information being shared is not known to be excluded information under Part 6A of the Act and is not restricted from sharing by any other law.

If the threshold is considered to be met, ISEs do not require consent from any person to share relevant information with other prescribed ISEs. Wherever reasonable and safe to do so, ISEs should, however, take into account the views of the children and relevant family members associated with the information, to inform their assessment.

The Ministerial Guidelines note that it is expected that prescribed ISEs will have policies and procedures in place that guide the use of CISS, consistent with the Act. Within these policies and procedures, ISEs should identify the roles within their organisation or service that are authorised to use CISS on behalf of the ISE.

1.3.1.3 Child Link Register (Child Link)

Part 7A of the Act legislated for the establishment of Child Link, a digital register designed to draw together information from existing government systems to create profiles for Victorian children. The purpose of Child Link, under the Act, is to improve wellbeing and safety outcomes for Victorian children through monitoring and supporting participation in government-funded programs and services. Child Link contains a profile for every Victorian child. While Child Link is not the focus of this review, it is a key enabler of CISS.

Child Link profiles include essential factual details about the child’s identity and their participation in early childhood and education services. Specifically, information entered on Child Link is limited by Part 46D of the Act to include only:

- basic personal details of a child, including the child’s full name, date of birth, place of birth and sex

- key family relationships, including the full names of persons with any parental or carer responsibility, as well as any siblings

- whether the child is Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander

- whether a child protection order has been made under the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005

- limited details of government-funded services (excluding the National Disability Insurance Scheme) in which a child is enrolled or participates, including details of their participation.

1.3.2 Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018

Operation of CISS is supported by the Regulations. The objectives of the Regulations are to prescribe:

- organisations and services as ISEs authorised and obliged to share information for the purposes of promoting child wellbeing and safety

- record keeping requirements that ISEs must comply with.

The Regulations also prescribe particular secrecy and confidentiality provisions in other legislation which can be overruled when sharing information in accordance with CISS.

1.3.2.1 Prescribed ISEs

Organisations and services are designated in the Regulations as prescribed entities based on their specific role and expertise within the sector, and because the information they possess may be valuable in promoting the wellbeing and safety of children.

Phased incorporation of prescribed ISEs

The incorporation of prescribed ISEs into the Regulations occurred in two distinct phases, each targeting different groups of organisations and service providers:

- Phase One prescribed secondary and tertiary services19

- Phase Two prescribed additional government agencies including key universal services, and funded service providers.20

The recommendations of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017) informed selection of workforces that should be prescribed as ISEs under CISS. Recommendation 8.7 reads:

"In establishing the information exchange scheme, the Australian Government and state and territory governments should develop a minimum of nationally consistent provisions to enable direct exchange of relevant information between a range of prescribed bodies, including service providers, government and non-government agencies, law enforcement agencies, and regulatory and oversight bodies, which have responsibilities related to children’s safety and wellbeing."

The Royal Commission also made a range of recommendations specific to information sharing in the education sector, particularly between schools when a child changes school. These recommendations, and the desire for alignment with prescribed workforces under the FVISS and MARAM reforms, informed the prioritisation of secondary and tertiary government services, the education sector and healthcare sectors in the first two phases of CISS implementation.

Phase One was rolled out when the Regulations initially took effect in September 2018. The entities prescribed under Phase One were selected for the initial rollout of CISS as it was considered their existing capability in formal risk assessment and management, complementary service functions and relatively small workforces (with the exception of Victoria Police) would allow for effective training and implementation of CISS in the first instance.

Phase Two of CISS commenced in April 2021, with the Regulations amended to prescribe a broader scope of universal service providers, ensuring prescription of services that interact with the vast majority of Victorian children.21

There is a total of 8,269 prescribed ISEs under CISS, with approximately 700 entities prescribed in Phase One and approximately 7,500 prescribed in Phase Two. Table 1.1 outlines the types of organisations and services prescribed as ISEs across the two phases.

Prescribed workforces were selected with consideration of the relative costs of implementation to the proposed ISEs and what had been provided for in the 2018-2022 State Budgets in terms of scope of training and support. The 2020 Regulatory Impact Statement identified the preferred option for Phase Two was estimated to prescribe around 7,500 workforces and an additional 236,000 workers. The preferred option was selected using a multi-criteria analysis which assessed each option’s anticipated effectiveness, risk of imposing infeasible requirements on ISEs and the prospective costs of implementation. The preferred option was selected primarily due to its prospectively high degree of effectiveness, combined with its relative feasibility for ISEs.

Table 1.1: Organisations and services prescribed as ISEs under Phase One and Phase Two of CISS (non-exhaustive list)

Source: The Department of Education

1.3.2.2 Record keeping requirements

Part 3 of the Regulations outlines specific record keeping requirements for ISEs. These requirements include documenting:

- the details of information shared, including the entity requesting the information, the time and date of sharing and the specific information shared, such as the content, source and recipient of the information

- the information that was requested, the information that was shared and any reasons for deciding to share or not share information related to the wellbeing and safety of children

- any consent received for sharing information and how informed decisions about whether and what information would be shared were made in cases where consent was not obtained

- a copy of any relevant documents, for example a family violence risk assessment or family violence-related safety plan

- security and access, including how the shared information will be securely stored and who will have access to it.

The Regulations are not prescriptive in how record keeping obligations are met, with records made and stored locally by the person or entity providing the information, depending on the needs, practices and requirements of the organisation or service.

The Regulations also specify record keeping obligations when a request is denied, specifically, the details of the request and why it was declined.

1.3.3 Amendments to intersecting Acts and information sharing provisions

CISS is one of many elements in Victoria’s legislative framework supporting data, privacy and information sharing, sitting alongside and interacting with a number of complementary schemes and systems.

The Children Legislation Amendment (Information Sharing) Act 2018 expanded the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 to include ISEs and Child Link users that were not previously subject to it. All ISEs covered by the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 must comply with the Information Privacy Principles in the Act, as well as the Health Privacy Principles in the Health Records Act 2001.

The Children Legislation Amendment (Information Sharing) Act 2018 also amended the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005, which simplified and streamlined the information sharing provisions within that Act to align with CISS. The amendments expanded the circumstances in which an authorised officer may direct an information holder to provide information related to a child’s safety or development.

1.3.4 Legal obligations of ISEs

The minimum obligations of ISEs include:

- the record keeping requirements as outlined in Section 1.3.2.2

- complying with a request for information from another ISE, and making requests or voluntarily sharing information if CISS’ requirements for sharing information are met

- sharing information in adherence to the Ministerial Guidelines.

It should be noted that the implementation of CISS and the associated culture change within child information sharing seeks to encourage further collaboration between services. This includes the proactive seeking and sharing of information to better support children and to improve the realisation of CISS’ intended benefits. However, it is noted that this implementation task and culture change is separate from the minimum obligations of ISEs under CISS.

It should also be acknowledged that CISS does not operate in isolation. For example, ISEs are also subject to the Child Safe Standards, the Reportable Conduct Scheme, and CISS is subject to the remit of the Commission for Children and Young People. Additionally, ISEs are subject to regulatory bodies such as the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner (OVIC), the Health Complaints Commissioner (HCC), and the recently established Human Services Regulator.

1.4 Key elements of CISS delivery model

1.4.1 Governance

Part 6A of the Act is jointly administered by the Minister for Children, Minister for Education and Minister for Health.

From commencement of the VCIS Reform, the Information Sharing and MARAM Steering Committee was established to oversee CISS, FVISS and MARAM implementation, supported by an Interdepartmental Committee and Working Group. In 2020, this body was disbanded, and CISS governance transitioned to a specific CIS Steering Committee (CISSC).

The CISSC is convened by VCISECS and includes membership from the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (including Family Safety Victoria), Department of Health, Department of Justice and Community Safety, Victoria Police, Courts Victoria, Department of Premier and Cabinet and Department of Treasury and Finance.

The purpose of the CISSC is to:22

- monitor the use and impact of the VCIS Reform

- evaluate the outcomes of the VCIS Reform

- oversee a Whole-of-Victorian Government (WoVG) workplan for implementing the Two-Year Review recommendations and funded activities under the 2021-22 State Budget Bid

- contribute to strategic direction on critical policy elements supporting the VCIS Reform

- provide strategic oversight and agree to actions and plans (e.g., budget bids, legislation and policy, etc.).

These governance arrangements reflect the legislative intent and shared responsibility for the VCIS Reform across numerous Victorian Government agencies.

The CISSC meets quarterly to discuss and report financial expenditure, implementation and training activities, demand on central units, and stakeholder concerns from each department involved in the implementation of CISS. Additional implementation activities such as the Change Plan 2022-23 and the MRF are presented by members of VCISECS to maintain transparency on progress of the implementation of CISS against communicated timelines and objectives. Each meeting further outlines any extreme or high-level implementation risks and proposed mitigation strategies for discussion amongst CISSC members and is supported by detailed meeting packs which contain the information and data referenced in each meeting.

1.4.2 Initial workforce training

CISS, FVISS and MARAM form part of the WoVG reforms in response to the Royal Commission into Family Violence. As a result, CISS and FVISS training was delivered together for Phase One ISEs, combined with an introduction to MARAM. Training development was led by the Department, with support from Family Safety Victoria. Swinburne University was commissioned to develop the suite of training materials. Box Hill Institute, Wodonga TAFE and GOTAFE were commissioned to deliver face-to-face training across Victoria. 23

Training was conducted between October and December 2018, within three months of CISS’ commencement. Training was delivered in a multimodal approach (face-to-face, e-learning, and self-directed online lectures) to allow for flexibility and choice for workforces based on their priorities. 24

1.4.3 Enquiry Line and inbox

The Enquiry Line and inbox have been open to Phase One prescribed organisations and services since the commencement of CISS in September 2018. This was originally a shared resource for queries related to FVISS, MARAM and CISS for most of the Phase One implementation period.

The Department took over operation of the Enquiry Line and inbox in 2019. Since then, the Enquiry Line’s focus has expanded to support Child Link and mandatory reporting enquiries for education workforces. The expanded functions are resourced separately to the Enquiry Line’s pre-existing functions.

1.4.4 Establishing Victorian Child Information Sharing Reform Outcome Measurement Framework

In 2020, the Department developed the Outcome Measurement Framework identifying the intended outcomes of the VCIS Reform, which are categorised by themes and timelines, and including seven short-term outcomes, 11 medium-term outcomes and six long-term outcomes.

In early 2023, the Department partially operationalised the Outcome Measurement Framework and is working with stakeholders within the Department and related agencies to ensure data is being collected in line with identified data sources.

The Outcome Measurement Framework was used in this Review to inform the development of a program logic as part of the Review framework. The Program Logic, along with the short-, medium- and long-term outcomes in the Outcome Measurement Framework are outlined in further detail in Section 1.6.3.2.

1.4.5 CIS Capacity Building Grants Program

The Department awarded grants to sector peak bodies in the 2021-22 and 2022-23 financial years to provide direct implementation support to prescribed sectors in CISS. This enabled grant recipients to provide practical support to workforces prescribed in CISS, providing information sessions, online resources, and opportunities to collaborate with other stakeholders.

1.5 Monitoring of CISS

In accordance with Section 41ZN and 41ZO of the Act, CISS is subject to an independent review of its operation and any adverse impacts within two and five years of commencement.

1.5.1 Two-Year Review of the Child Information Sharing Scheme

In 2020, the Two-Year Review of CISS was undertaken, covering the period September 2018 to September 2020. The final report was tabled in Parliament on 18 March 2021.25 The Two-Year Review focused on the implementation and operation of CISS during its first two years of operation. Only Phase One ISEs were prescribed in the Regulations at the time of the Two-Year Review.

The purpose of the Two-Year Review was to:

- determine to what extent CISS had been implemented effectively

- identify the key enablers and barriers to implementation

- determine to what extent CISS was achieving its intended outcomes

- consider and identify any adverse impacts of CISS

- assess the success of prescription of ISEs

- assess impacts on diverse and disadvantaged communities

- include recommendations (as necessary) on any matter addressed.

The Two-Year Review made a number of key findings aligned with these areas of inquiry and made 13 recommendations, of which the Victorian Government supported nine in full, three in principle and one in part. Detail of the recommendations, the government response to each and the status of implementation are detailed in Appendix D of this report. The evidence, data and findings from the Two-Year Review are referenced throughout this report.

Two-Year Review and Five-Year Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme

The monitoring of CISS occurs alongside the monitoring of FVISS. In 2020, the Legislative Two-Year Review of FVISS (FVISS Two-Year Review)26 was undertaken to review its implementation between October 2017 to December 2019. At the time of the FVISS Two-Year Review, only Phase One ISEs were prescribed under the Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Regulations 2018. The FVISS Two-Year Review made 22 recommendations.

In 2023, the Legislative Five-Year Review of FVISS (FVISS Five-Year Review)27 was undertaken to review the legislative and regulatory framework for FVISS, Central Information Point, and MARAM Framework. The FVISS Five-Year Review made 16 recommendations. The FVISS Five-Year Review was tabled in Parliament in August 2023.

While FVISS is not within the scope of this Review, it intersects with CISS as part of the WoVG approach to information sharing in response to the Royal Commission into Family Violence. This Review will refer to relevant findings from the FVISS Five-Year Review as appropriate.

Source: Victorian Government, Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme reviews.

1.6 Five-Year Review of the Child Information Sharing Scheme

1.6.1 Purpose of this report

This report is the Five-Year Review of CISS, covering the period from September 2018 to September 2023.

The rollout of Phase Two of CISS in 2021 expanded the scope of prescribed entities to include those ISEs listed in Table 1.1. Consequently, this Review has considered the operation of CISS across a significantly increased number of organisations and service providers in comparison to the Two-Year Review, spanning ISEs prescribed under both Phase One and Phase Two.

1.6.2 Review questions

The scope of this Review was to consider two key review questions and nine sub-review questions organised into the three domains of implementation, effectiveness and legislative and regulatory settings (see Sub-review questions of the Five-Year Review below).

The two key review questions are:

- to what extent has the operation of CISS achieved its intended reform outcomes to date?

- do the findings from the review support any considerations for changes to the legislative and/or regulatory settings of the reforms?

Sub-review questions of the Five-Year Review

Review Domain 1: Implementation

- Is CISS being implemented within its scope as defined by Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005?

- What have been the key enablers and barriers to implementation?

Review Domain 2: Effectiveness

- To what extent has CISS achieved its intended outcomes to date? How close is CISS to achieving its medium-term (5-year) outcomes and are there early indicators of CISS achieving its long-term (10-year) outcomes?

- Is there any evidence of negative impact of CISS on diverse communities and communities experiencing disadvantage?

- Are there any unintended consequences of implementation – both positive and negative?

Review Domain 3: Legislative and regulatory impact and settings

- Are there any unintended consequences of interpretation – both positive and negative?

- Do the findings of the review support any considerations for changes to the legislative settings of CISS?

- What are the impacts of the current Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018 and what are the issues related to the Regulations (if any)?

- What could be done to address the issues, if any, of the Regulations? When answering this, consider both Regulatory amendment and non-Regulatory options.

1.6.3 Methodology overview

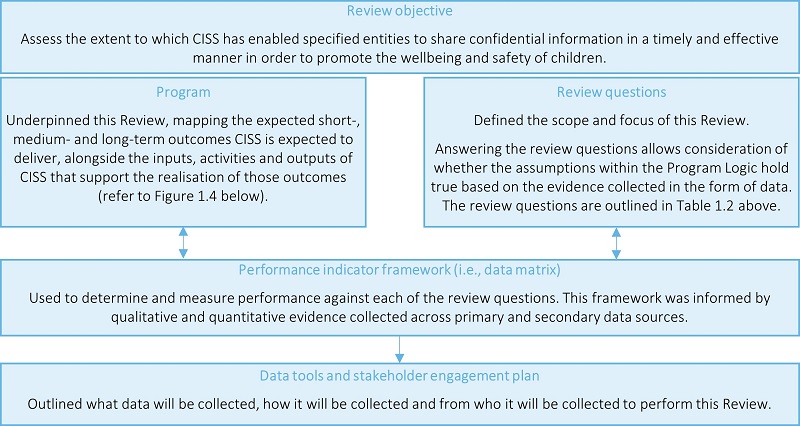

An overview of the methodology used in undertaking this Review is outlined below, with a detailed description of the methodology provided in Appendix B. To guide this Review, an evaluation framework was developed (see Figure 1.3 below).

1.6.3.2 Program Logic development

During this Review, the Outcome Measurement Framework was refined to ensure the intended outcomes remain accurate based on CISS developments since 2020. The Outcome Measurement Framework was revised to include:

- two additional short-term outcomes (SO8 and SO9 in Figure 1.4 below) and an additional long-term outcome (LO7 in Figure 1.4 below)

- the inputs, activities and outputs of the VCIS Reform

- assumptions regarding the implementation of CISS

- current contextual factors directly relevant to the implementation of CISS

- longer-term impacts intended to be delivered by CISS.

The revised Outcome Measurement Framework is referred to as the Program Logic. This Review assesses government’s progress towards realising the intended outcomes of CISS as defined within the Program Logic. The intended outcomes of the Program Logic are provided in Figure 1.4 below and the full Program Logic is provided in Appendix A.

Figure 1.4: Intended outcomes from the VCIS Reform Program Logic Model

Source: Deloitte Access Economics.

1.6.3.3 Data collection

A mixed-methods approach was adopted to obtain the relevant information and best respond to the review questions outlined in the Sub-review questions of the Five-Year Review (see above). Secondary data was initially collected through a literature and desktop review, consisting of publicly available literature, program data, previous reviews and documents, case studies and case files provided by the Department. Primary data was then collected through stakeholder consultation, consisting of:

- semi-structured interviews and focus groups with government, peak body, union and workforce stakeholders, undertaken between August and November 2023

- an online survey distributed to professionals who work in ISEs across workforces, distributed throughout September and October 2023. Respondents included Victorian Public Sector professionals (e.g., 61 respondents nominated the Department as their organisation), as well as professionals in non-public sector organisations, for example staff at independent schools and General Practitioners.

Detail on the design and distribution of the CISS Workforce Survey, as well as the survey questions and responses are provided in Appendix C.

To ensure ethical engagement was conducted with key workforces throughout the engagement in accordance with the principles and guidelines set out in the National Statement for Ethical Conduct in Human Research, ethics applications were submitted and approved by the Justice and Human Research Ethics Committee, the Department of Education (Research in Schools and Early Childhood Settings) and the Victoria Police Research Coordinating Committee.

The data collected brought together overlapping, complementary and contradictory information. Systematic thematic analysis was undertaken to bring this information together to identify emerging themes and enable the evaluation to present deep and balanced insights on CISS and the extent to which its intended objectives have been achieved.

1.7 Structure of this Report

This remainder of this report has been structured around the review domains, as follows:

- Chapter 2: Implementation

- Chapter 3: Effectiveness

- Chapter 4: Legislative framework

- Chapter 5: Recommendations

- Appendices containing supporting information.

Notes

10 Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines – Guidance for Information Sharing Entities, 4.

11 Second Reading Speech, Children Legislation Amendment (Information Sharing) Bill 2017

12 Victorian Government, Children, Youth and Families Act (2005)

13 Victorian Government, Privacy and Data Protection Act (2014)

14 Victorian Government, Health Records Act (2001)

15 Victorian Government, Roadmap for Reform: strong families, safe children – The first steps (2016)

16 Victorian Government, Early Childhood Reform Plan – Ready for kinder, ready for school, ready for life (2017)

17 Victorian Government, Victoria’s 10-Year Mental Health Plan (2015)

18 Victorian Government, Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines – Guidance for information sharing entities

19 Specified in the Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018. Prescribed secondary and tertiary services include key frontline workforces, such as Child Protection, Maternal and Child Health and Victoria Police.

20 Specified in the Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Amendment Regulations 2021. Prescribed universal service providers include universal education and health services, such as schools, public hospitals, Victorian council kindergarten, supported playgroup and out of school hours care services.

21 Victorian Government, Regulatory Impact Statement – Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Amendment Regulations 2020 (2019).

22 Child Information Sharing Steering Committee Terms of Reference.

23 Child Information Sharing Steering Committee Terms of Reference.

24 Department of Education and Training (2019). Information Sharing and Introduction to MARAM Training. Evaluation Report.

25 ACIL Allen Consulting, Child Information Sharing Scheme Two-Year Review (report commissioned by the Department of Education and Training, December 2020)

26 Monash University, Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Legislative Scheme (report commissioned by Family Safety Victoria, 30 May 2020)

27 Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor, Legislative review of family violence information sharing and risk management: reviewing the effectiveness of Parts 5A and 11 of the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (Vic) (May 2023).

Implementation

2.1 Review questions addressed in this chapter

This chapter responds to the following review questions:

- Is CISS being implemented within its scope as defined by Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005?

- What have been the key enablers and barriers to implementation?

2.2 Is CISS being implemented within its scope as defined by Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005?

2.2.1 Scope of CISS as defined within Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005

The legislative framework underpinning CISS has been established and defined by Part 6A of the Act. It outlines the key principles that ISEs are required to follow in sharing confidential information in a timely and effective manner to promote the wellbeing and safety of children. These principles are that ISEs should:

- give precedence to the wellbeing and safety of a child or group of children over the right to privacy

- only share confidential information to the extent necessary to promote the wellbeing or safety of a child or group of children, consistent with the best interests of that child or those children

- work collaboratively in a manner that respects the functions and expertise of each information sharing entity and restricted information sharing entity

- seek and take into account the views of a child and the child’s relevant family members, if it is appropriate, safe and reasonable to do so

- seek to preserve and promote positive relationships between a child and the child’s family members and persons of significance to the child

- be respectful of and have regard to a child’s social, individual and cultural identity, the child’s strengths and abilities and any vulnerability relevant to the child’s safety or wellbeing

- take all reasonable steps to plan for the safety of all family members who are believed to be at risk from family violence

- promote the cultural safety and recognise the cultural rights and familial and community connections of children who are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander or both

- seek to maintain constructive and respectful engagement with children and their families.

Part 6A restricts information sharing under CISS to ISEs prescribed through the Regulations. CISS does not apply to all persons in Victoria. As such, CISS’ current scope is significantly determined by the Regulations.

Part 6A also outlines the threshold for sharing information under CISS, any potential offences from improper data sharing and use, protections, records management, and the relationship of CISS with other information sharing and handling acts like FVISS, the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 and the Health Records Act 2001.

In determining whether CISS has been implemented within its scope, this Review has focused on the extent to which implementation activities have supported:

- prescribed professionals to share information through CISS as intended

- the systems change envisaged by Part 6A and the Program Logic (Appendix A)

- government oversight of CISS, including monitoring and compliance.

This Review has also discussed the activities undertaken in response to recommendations from the Two-Year Review, and areas of legislative scope which may benefit from further attention.

2.2.2 Supporting prescribed professionals to share information as intended

2.2.2.1 Training for prescribed professionals

Phase One

Phase One face-to-face training was attended by approximately 2,000 participants across 35 training sessions in 25 locations across metropolitan and regional Victoria.28, 29 Most attendees were from the former Department of Health and Human Services and their funded agencies (58 per cent), with the second highest being from Family Safety Victoria (23 per cent). In 2019, a further 1,058 participants across the then Department of Health and Human Services workforces participated in face-to-face training.30

Additional workforce-specific training and change management was delivered by the Department of Health, the Department of Justice and Community Safety, Victoria Police and Court Services Victoria.

An online LMS for the Information Sharing and MARAM reforms was launched in December 2018. The platform contains face-to-face, webinar and eLearning training on information sharing developed by the Department as well as training packages for other departments, and it is used by prescribed ISEs.

The LMS supplements, and is complementary to, other resources and materials made available to ISEs through a variety of platforms during Phase One. These are articulated in further detail in Section 2.2.2.2 below.

Phase Two

Phase Two workforces undertook similar training and skills development activities as Phase One workforces (outlined in Section 1.4.2). These activities commenced in March 2020 ahead of the rollout from April 2021. Training and skills development activities are intended to be finalised in June 2025.

Over 2,100 individuals in education workforces attended 56 face-to-face Information Sharing Information Sessions between June 2022 and June 2023. In addition to this, 36,977 professionals accessed training online through the LMS on CISS, FVISS and MARAM. Most professionals who accessed the LMS were from the Department and their funded agencies (56 per cent), with the second highest from the Department of Health and their funded agencies (18 per cent, n=40,103).31

The Department also delivers activities for its funded agencies and aims to deliver training and change management activities to approximately 20,000 participants over three stages between January 2020 and June 2024.32 These training programs and modules were refined during Phase Two to focus on meeting specific education workforce needs.33 The face-to-face and webinar training has incorporated reference to further reforms as they have commenced (e.g., the new Child Safe Standards) and has seen a reduction in duration to the minimum necessary to allow safe sharing. This has seen the length of training required reduce from 1 day, to 4.5 hours, to the current 1.5-hour duration. Workforce-specific training and change management is procured by the Department of Health, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, the Department of Justice and Community Safety, Victoria Police and Court Services Victoria.

Alignment of training to the scope of CISS

Sector-specific training developed and delivered to date by each department comprehensively addresses the requirements of Part 6A of the Act, as it outlines definitions, principles and guidance for permitted information sharing under CISS for ISE workforces within their portfolios. The training materials provide information on thresholds for information sharing, who to share information with, when to seek and consider the views of a child and relevant family members, and record keeping. They are supported by relatable case studies and videos where relevant.

The approach to training has enabled key departments and agencies to develop and deliver content that is tailored for their workforces. For example, while the Department has developed WoVG training materials for use across prescribed workforces, it has also developed tailored resources for education workforces.34, 35, 36 This specificity has emerged as an enabler for education workforces and agencies to consolidate their understanding of CISS. A survey of the Department’s workforces rated eight of the ten information sharing courses as high on the satisfaction scale. There is an opportunity to ensure tailored training and other materials (e.g., case studies, guidance) for other workforces is made publicly available and therefore, more accessible to ISEs.

2.2.2.2 Resources to support prescribed professionals

A broad range of information about CISS is available through the Victorian Government’s “Information Sharing and MARAM reforms” webpage, including:

- Ministerial Guidelines: The Guidelines explain how prescribed ISEs should handle confidential information responsibly, safely and appropriately under CISS. The Guidelines also set out how the legislative principles of CISS are to be applied.

- Guidance materials: These include organisational readiness guidance to support ISEs to transition policies and procedures within their organisation; user guides for ISEs; tips and factsheets for engaging with children and families about information sharing; checklists for making and receiving requests; record keeping examples; and complaints processes.

- Communications materials: These include fact sheets and flyers.

This is in addition to the ISE database, hosted on a bespoke website, that identifies which entities can share or request information through CISS.

During Phase Two, there was a significant focus from the Department on improving resources available to CISS users and ISEs outside of training activities, as part of the WoVG change management strategy to respond to the findings of the Two-Year Review. Additional resources developed included:

- a Contextualised Guidance and Toolkit resource for ISEs in education and health and wellbeing workforces which complements the face-to-face training and eLearning modules. This resource has been revised into a new toolkit, through codesign with impacted workforces, that was launched in January 2024

- more factsheets developed and released iteratively, including more targeted factsheets for specific sectors, workforces and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

- additional case studies and "bright spots" examples, to illustrate how CISS works in practice and share success stories across sectors

- video resources to target service users and build service awareness

- development of guidance on roles and responsibilities within CISS.

Some of these resources were developed through the Supporting Reform in Place project and the CISS Capacity Building Grants program, which are discussed in further detail at Sections 2.2.3.2.1 and 2.2.3.2.2.

CISS Decision Making Tool App

One example of such a resource is the CISS Decision Making Tool App, which was developed by the Victorian Aboriginal Children & Young People’s Alliance (VACYPA) for ACCOs to use. Before using the Decision Making Tool, VACYPA advises that prospective users ensure they have completed their relevant Victorian Government Information Sharing Training. The Decision Making Tool asks users a series of questions about why, how and with whom information may be shared, and advises them of the legislative three-part threshold test for sharing information. The Decision Making Tool also advises users that they must not input the names of any individuals, their personal information or any other identifying information as part of their responses. While users answer the questions, they can refer to links to the Ministerial Guidelines and to a page of tips for using CISS as additional guidance sources. At the end of the questions, users are invited to download a record of their answers to assist with fulfilling their record keeping requirements.

These steps aim to inform users of the relevant considerations regarding CISS, so they can confidently exercise their professional judgement over when to use CISS. The Decision Making Tool does not provide decisions on whether the user should engage in information sharing activities. The invitation to download a record of their answers encourages compliance with CISS’ record keeping requirements.

Source: The Victorian Aboriginal Children & Young People’s Alliance, CISS Decision Making Tool.

2.2.2.3 Advice and support through the Enquiry Line and email inbox

Phase One

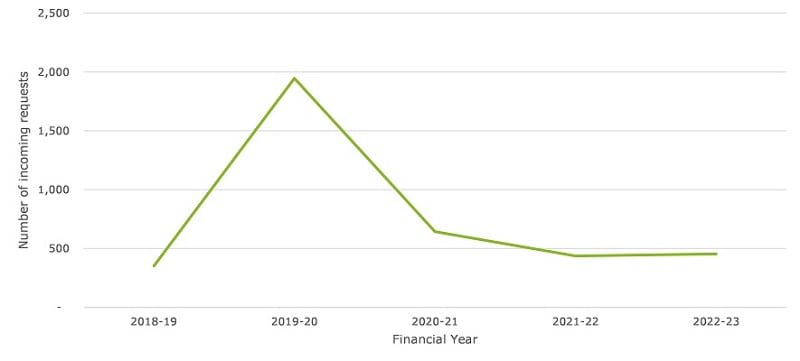

The Enquiry Line is a shared resource that responds to queries related to CISS, FVISS and MARAM. It has been in operation for CISS since September 2018 in line with the prescription of Phase One ISEs. It was originally operated by the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing in 2018 with operation assumed by the Department from 2019.

The Two-Year Review found that the majority of enquiries received by the Enquiry Line between January 2019 and June 2020 related to both CISS and FVISS (39 per cent) or only FVISS (29 per cent), while 11 per cent of enquiries in this time related only to CISS. Of these enquiries, 92 per cent sought to verify ISEs, seek guidance around consent and sharing confidential information, access training or resources, seek guidance around determining the threshold for information sharing, the extent of information sharing, and actions for when an information sharing request is refused.37

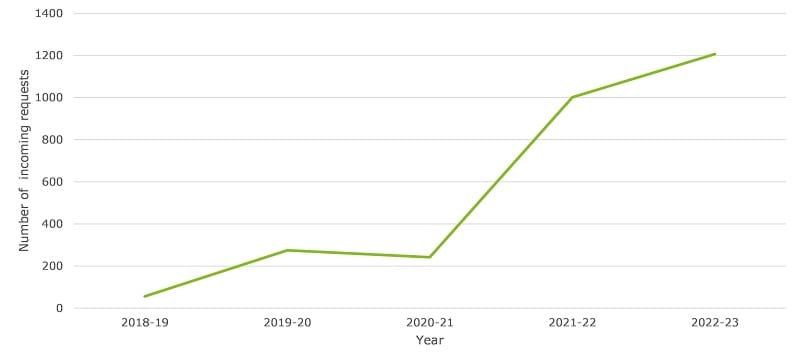

Phase Two

The Enquiry Line continued to be operated by the Department throughout Phase Two. Since the Two-Year Review, the Department expanded the system to:

- include phone and email enquiries (to be tracked in Microsoft Excel, which was replaced by professional call tracking software in September 2021)

- extend operational hours

- enhance the data recording system.

Additionally, Enquiry Line staff were supported by an Operations Manual and a Confluence Reference Manual to refer to answers to common questions.

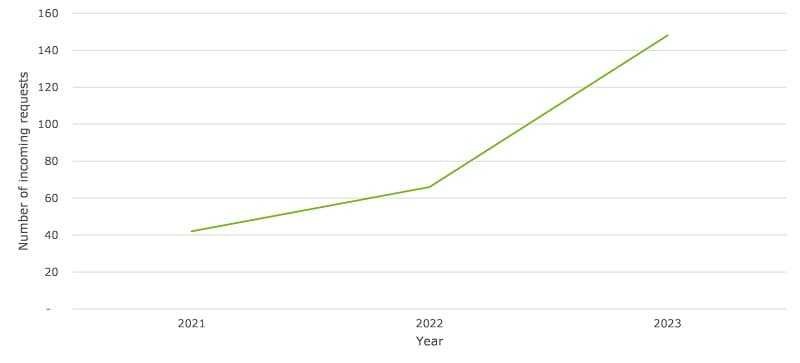

This Review found that use of the Enquiry Line grew significantly compared to the period reviewed in the Two-Year Review, with 12,568 calls and emails managed from January 2021 to September 2023.38

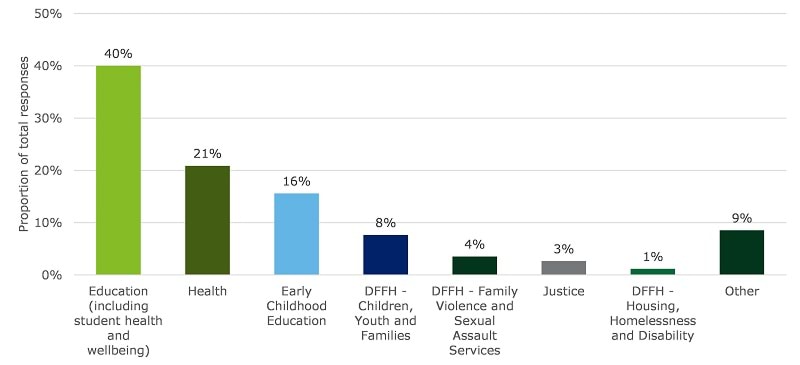

Analysis of the queries data provided relating to the period January 2021 to end of September 2023, reveals that the majority of queries managed by the Enquiry Line related to mandatory reporting (70 per cent), while 15 per cent related to CISS and ten per cent related to Child Link (n=12,568). This data includes enquiries that related to multiple subject areas.

Of the CISS-related enquiries, the majority related to training (74 per cent), including LMS queries, with the next most common category relating to resources, policy, guidance or other support (19 per cent).

2.2.2.4 Stakeholder engagement and communications plans and activities

Phase One

The Department developed the WoVG Integrated Stakeholder Engagement Strategy: CISS and Child Link in 2020. The Strategy describes the overarching communication and engagement approach, key messages, and engagement objectives for CISS and Child Link, with reference to FVISS and MARAM.39

Due to the inter-related reforms reducing family violence and promoting child wellbeing and safety being delivered by different agencies, the Strategy is applicable for the Department, the Department of Health and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (including Family Safety Victoria). The Strategy is supported by Engagement Project Plans and Communications Action Plans to drive messaging to key CISS workforces.

Phase Two

The Department developed a dedicated CISS Phase Two workplan across the stakeholder engagement, communications and governance workstreams. Similar to Phase One activities, this plan included FVISS, CISS, Child Link and MARAM activities. This has been further iterated with subsequent communications action plans in 2022-23 and 2023-24, targeting education sector stakeholders.

Some sector-specific or targeted engagement and communications activities were developed through the CIS Capacity Building Grants program, which is discussed in further detail at Section 2.2.3.2.2 below.

2.2.3 Supporting systemic change

2.2.3.1 Family Safety Victoria Sector Grants Program

The Family Safety Victoria Sector Grants Program was introduced in the 2017-18 financial year and provided funding to key representative and state-wide bodies for implementation of the information sharing and MARAM reforms. The program focused on implementation of the information sharing reforms in a family violence context. In 2020-2021, grant funding of $1.5 million was allocated to projects delivering tailored initiatives to key workforces relating to all three reforms.

Grants were accessed by peak/lead bodies including the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare, Municipal Association of Victoria, Council to Homeless Persons, Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association and the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA).

2.2.3.2 CISS Change Program

In response to the Two-Year Review, the Department implemented the CISS Change Program which consists of sectoral and place-based change initiatives to support the awareness, understanding and adoption of CISS in prescribed ISEs and their workforces. The CISS Change Program was supported by a dedicated implementation strategy, funding and regular reporting to the CISSC.

2.2.3.2.1 Supporting Reform in Place project

The CIS Supporting Reform in Place project aims to embed and uplift place-based and cross-sectoral networks of ISEs to facilitate and support information sharing and practice integration around the child and family, including cohorts experiencing vulnerability and disadvantage.

The project’s key objectives include:40

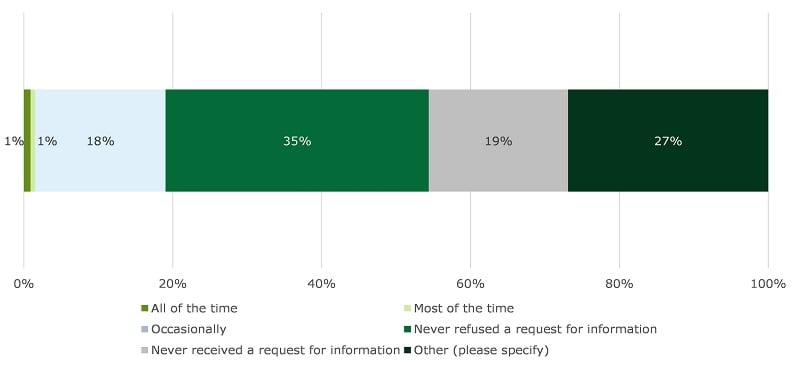

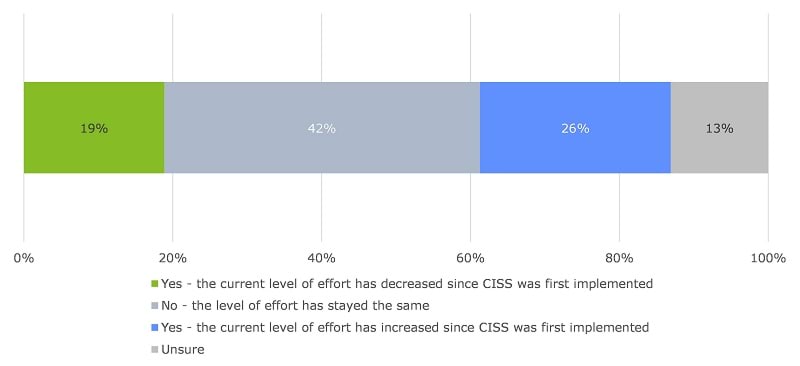

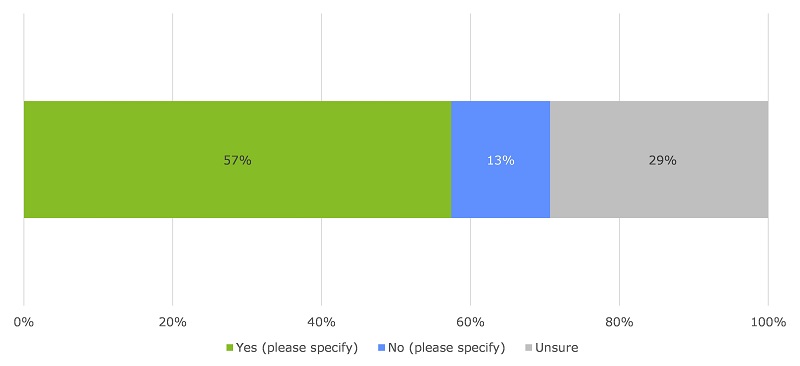

- adopting and trialling a place-based approach to embedding CISS amongst ISE workforces