3.1 Review questions addressed in this chapter

This chapter responds to the following review questions:

- To what extent has CISS achieved its intended reform outcomes to date? How close is the reform to achieving its medium-term (5-year) outcomes and are there early indicators of the reform achieving its long-term (10-year) outcomes?

- Is there any evidence of negative impact of the reform on diverse communities and communities experiencing disadvantage?

- Are there any unintended consequences of reform (implementation) – both positive and negative?

3.2 Outcomes assessed in this Review

It should be noted that the majority of the evidence presented in this chapter relates to the initial impacts demonstrated through CISS’ implementation, which largely pertain to building awareness and understanding of CISS. There is less evidence demonstrating the extent to which some medium- and long-term outcomes have been achieved. Additionally, it is acknowledged that there will always remain a level of uncertainty when measuring the long-term child wellbeing and safety outcomes attributable to CISS due to a range of factors. These include the complex nature of factors affecting child wellbeing and safety, information sharing being one component which can potentially impact these outcomes, and the lack of a standard definition or framework for wellbeing. As such, more time and investment of resources is required to allow for further embedding of CISS consistently across service systems to better demonstrate the achievement of medium- and long-term outcomes.

This section considers the short-term and medium-term outcomes in Table 3.1 below.

Table 3.1: Relevant short- and medium-term outcomes to Chapter 3

Short-term outcomes

| Program | Logic Model Outcomes |

|---|---|

| SO6 | ISEs consider the views of children and/or parents where appropriate, to inform professional judgement. |

| SO7 | ISEs demonstrate quality, timely and appropriate child information sharing. |

| SO8 | Increased early identification of potential issues, risks and/or harm to children. |

| SO9 | Organisations provide appropriate support to professionals to facilitate implementation of the VCIS Reform. |

Medium-term outcomes

| Program | Logic Model Outcomes |

|---|---|

| MO1 | Improved service system coordination and collaboration in the interests of the child. |

| MO5 | High human service job satisfaction. |

| MO6 | ISE workforces are confident to share child information. |

| MO7 | Professionals are collaborating to provide integrated and cohesive services to children and their families. |

| MO8 | A shared understanding and commitment to child wellbeing across services and communities. |

| MO9 | Users have an improved understanding of a child’s circumstances, enabling earlier identification of needs and risks. |

| MO10 | Professionals have increased confidence in sharing information appropriately and effectively, shifting the risk averse culture around information sharing. |

| MO11 | Professionals effectively identify issues, risks and vulnerabilities to better inform decision-making and further appropriate support and intervention. |

Note: Refer to Appendix A for more detail on the Program Logic.

3.3 To what extent has CISS achieved its intended short- and medium-term reform outcomes to date?

The understanding of CISS by its users is critical to achieving program outcomes related to child wellbeing and safety. Users must comprehend CISS’ principles, guidelines, and the specific circumstances under which information can be shared. Without a clear understanding, professionals may hesitate or inadvertently misuse CISS, potentially leading to delays in taking timely and appropriate action to protect Victorian children in need. This section details evidence of the understanding of CISS among prescribed ISEs, delineating between Phase One and Phase Two entities where possible.

This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of CISS in realising its intended short- and medium-term outcomes as defined within the Program Logic. Progress against outcomes have been described in order from: 1) building understanding of CISS among ISEs; 2) utilisation and adoption of CISS among ISEs; and 3) building a shared responsibility and commitment for child wellbeing and safety.

3.3.1 A shared understanding of the purpose of CISS

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcome MO8.

Responses to the CISS Workforce Survey showed that respondents have a clear understanding of the scope of CISS as defined by the Act as demonstrated through CISS training materials and communications. For example, the successful delivery of initial training highlighted in Section 1.4.2 resulted in a high overall satisfaction rate among Phase One workforces who participated in the training. The usefulness of the training as reported by stakeholders has then translated into a generally positive perception of stakeholders in their understanding of CISS.

“It is helpful that there is now a shared understanding between services/systems about information sharing.” – Phase One stakeholder

However, workforces’ understanding of CISS is varied. Half of CISS Workforce Survey respondents agreed, and a further 28 per cent strongly agreed that they would benefit from more training on CISS (n=83). Similarly, stakeholders consulted in this Review indicated they believe that further training is required to address the varied levels of understanding of CISS between workforces, sectors and regions.

It is noted that understanding of CISS was higher for individuals who benefitted from both training and supporting place-based activities (e.g., the CIS Reform in Place Project and the CIS Capacity Building Grants program). For example, a Phase One education professional who had benefitted from the CIS Reform in Place Project reported a stronger understanding and practice of CISS. The stakeholder noted, “[CISS] has led to significant system improvements and a shared, deep commitment to understanding what’s in the best interests of the child, particularly in cases of transition of services. There is a higher priority given to supports required for the family as well as supports for the child.” This highlights the strength of combined training and place-based support to consolidate ISE’s knowledge of CISS’ purpose and principles.

In comparing the understanding of CISS between Phase One and Phase Two ISEs, who gained access to CISS three years later, certain differences are anticipated. Phase One ISEs, having had earlier access to CISS, are likely to exhibit a more established and nuanced understanding of its objectives and use in practice. Phase Two ISEs, while having recent access to CISS, may benefit from the experiences and lessons learned by Phase One ISEs. The key findings and differences between the phases are explored in the following sections.

3.3.1.1 Understanding of CISS among Phase One workforces

The CISS Workforce Survey indicated varying levels of confidence and understanding regarding CISS among Phase One workforces. A substantial 72 per cent of respondents either agreed (62 per cent) or strongly agreed (10 per cent) that they have a good level of understanding of CISS, suggesting a majority with confidence in their understanding (n=330). However, 18 per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, indicating a group with uncertain or ambiguous knowledge. 5 per cent disagreed, possibly reflecting some knowledge but a lack of confidence, while 4 per cent strongly disagreed, implying minimal or no understanding. These results were corroborated by stakeholders consulted in this Review, including the identification of challenges or barriers which have hindered a good level of understanding among workforces in some instances.

“Individuals and organisations are at different levels of understanding. At different sites, people are well aware of the CISS and are using it. A lot of organisations have limited knowledge and are just quite beginning.” – Phase Two stakeholder

Stakeholders in the health sector reflected the Department’s focus on increasing awareness of CISS and building skills in child mental health for their members, aiming to boost their confidence in addressing child wellbeing concerns. While there was acknowledgement of a generally good understanding among professionals in the sector, the need for improvement, particularly in instilling confidence in using CISS when specific situations arise was also emphasised. Stakeholders noted that in certain sectors, information sharing is integrated into daily work, whereas for many nurses for example, it may only surface periodically, necessitating better guidance on accessing resources.

For stakeholders within the broader child and family services (including family violence), levels of understanding and confidence vary among professionals regarding the use of CISS. While information is available, there are variations in organisations’ effectiveness in disseminating this information to their staff. Notably, there is a perceived lack of clarity for services whose roles are not solely to work with children, creating uncertainty about their roles within CISS and in addressing children’s wellbeing concerns. This lack of clarity extends to the identification of who is prescribed to share information and points to implementation challenges, with some professionals unaware of the existence of an ISE list for reference. Additionally, there is a need to enhance awareness of available resources that can support professionals in their information sharing efforts.

There are different working understandings of “wellbeing” amongst local government, justice, family safety, health, and education stakeholders. The Department has recognised this in the Ministerial Guidelines by allowing for sector-specific application of the definition and defining wellbeing thresholds in a manner that is appropriate to their industry and context. For example, a Phase One stakeholder noted, “the concept of wellbeing and proactive sharing is very different to working in courts or justice.”

“Wellbeing has been given a [weak definition] and not given as much significance. It jeopardises the legitimacy of the Scheme” - Phase One stakeholder

Additionally, Phase One workforces tended to see wellbeing as being one of many components that come under the category of safety, rather than wellbeing being its own category that is distinct from safety. For example, a Phase One stakeholder noted, “in practice, safety and risk always supersede wellbeing as people always rush to look at immediate safety. Child wellbeing is not prioritised as much.” Due to these inconsistent definitions and thresholds, it is difficult for this Review to determine how effective implementation activities have been in promoting the wellbeing of children.

A common theme among Phase One workforces is the expressed need for greater clarity in defining roles and responsibilities, especially for services not specifically funded for child-related work, such as those in the family violence sector. Many stakeholders expressed awareness and implementation challenges, often related to a lack of knowledge about essential resources. Capacity building was consistently emphasised, with a focus on understanding how information sharing is meant to be utilised, particularly when engaging with young people. Moreover, the availability of resources and comprehensive training emerged as vital factors influencing professionals’ confidence and effectiveness.

3.3.1.2 Understanding of CISS among Phase Two workforces

Similar to Phase One workforces, Phase Two workforces’ confidence in their understanding of CISS was mixed. 64 per cent agreed and a further 10 per cent strongly agreed that they were confident in their understanding of CISS (n=243). However, the remaining ISEs (26 per cent) neither agreed nor disagreed (16 per cent) or disagreed (6 per cent disagreed and a further 4 per cent strongly disagreed) that they are confident in their understanding of CISS. A large proportion of respondents (78 per cent) to the CISS Workforce Survey also indicated they would benefit from more training on CISS (30 per cent strongly agreed while a further 48 per cent agreed, n=82).

Phase Two stakeholders in the early childhood sector highlighted several challenges regarding information sharing within services, including the intersection between CISS, FVISS and MARAM. There is a noticeable increase in awareness of these schemes, although the understanding of their details remains limited until professionals receive specific requests for information.

Stakeholders emphasised the value of sharing information among various services, such as schools, psychologists, and maternal and child health, to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of individuals’ needs. Additionally, some agencies have established central information sharing schemes across CISS and FVISS. However, the abundance of resources pertaining to CISS and FVISS may have led to confusion, indicating a need for simplification. While ISEs’ understanding of the high-level principles of information sharing develops, further work is required to translate understanding into practice. For example, stakeholders expressed the need for further support in the form of developing case studies to provide meaningful examples of CISS’ application in real-life scenarios.

“There are reems (sic) of information which services are provided with may create confusion and ambiguity. It could be simpler, and therefore clear up some of that confusion.” – Phase Two stakeholder

Schools highlighted several challenges relating to awareness and comfort within schools regarding information sharing. A key challenge reported is the apprehension towards information sharing among schools, driven by a fear relating to parents' reactions, as there is no requirement for consent to share information. Additionally, stakeholders reported there is a perceived disconnect between the Department’s understanding of the education sector’s needs and what has transpired in practice. Stakeholder feedback provided through the CISS Workforce Survey observed that training has been legislation-focused. While this Review recognises the need to inform workforces of their obligations under the Act, stakeholders have suggested that this focus has limited the application of the materials by professionals across distinct sectors and workforces, particularly those that provide specialised services or operate in regional areas. For example, education stakeholders more broadly requested case studies to contextualise the use of CISS in real-life situations to improve their understanding of information sharing. Without this tailored support, stakeholders have reported a preference in some instances to share information through other mechanisms than CISS.

“Give schools bite-sized chunks of usable information such as flow charts and graphics and contextualised settings. Help us understand the prospective benefit of information sharing in our settings. We also need best practice examples on if there was an example of how information sharing helped children and families and the impact of following the process in a clear and considered way.” – Phase Two stakeholder

Feedback from educators suggested that training on CISS should be made mandatory. They expressed a desire for a more streamlined and comprehensive approach to training, potentially under a single umbrella (combining the information sharing schemes), as the current system was reported to be confusing.

Stakeholders indicated further strengthening of available materials and resources is required to address knowledge gaps across both Phase One and Phase Two workforces. For example, a stakeholder from the early childhood sector indicated, “practitioners seem to understand FVISS and MARAM, but that real proactive wellbeing aspect is challenging, especially for certain sectors. We’re finding this even in the workshop participation.” Additionally, a stakeholder from the education sector noted that the definition of wellbeing had been communicated through the training materials and resources, but not to the extent required for ISEs to effectively share information for the purpose of promoting wellbeing.

Stakeholders from local government highlighted varying levels of understanding within the sector, which can fluctuate due to factors such as staff turnover. This fluctuation is more noticeable when education efforts for CISS are continuous rather than when there are periodic intensive education initiatives. It was also reported that keeping understanding high about specific pieces of legislation was a challenge. Furthermore, the early adoption of CISS in the sector has created difficulties in determining which other entities are prescribed. Despite these challenges, there was perceived to be a strong awareness among the workforces about their obligations in the sector.

The identified challenges in the early childhood and education sectors take on added significance as they represent Phase Two entities, implying that they have not had as much time with CISS as Phase One entities. The relatively recent exposure to CISS may explain the varying levels of awareness and understanding reported in these sectors. This shorter timeframe with CISS has likely contributed to the observed disconnect between the high-level principles and actual application or adoption of CISS. The importance of simplification, case studies, and tailored support becomes more evident when considering the shorter period of engagement with CISS. In contrast, services delivered by local government councils, though also Phase Two entities, appear to have a strong awareness of their obligations. This is likely due to the Municipal Association of Victoria being a grant recipient in both rounds, which has allowed them to work closely with local councils, resulting in an improved application of CISS in a different context relative to other workforces, and an ability to more quickly adapt to CISS’ requirements.

Overall, while there is some distinction in experiences between Phase One and Phase Two workforces, there is a clear need for ongoing, tailored support and education as different workforces embed CISS in day-to-day practice.

3.3.2 Understanding of a child’s circumstances to enable early identification of needs and risks

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcome MO9.

In the CISS Workforce Survey, the majority of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that CISS had improved their organisation’s ability to identify risks to children early (73 per cent, n=330). There were no significant differences between Phase One (72 per cent, n=84) and Phase Two (73 per cent, n=243) in terms of ability to identify risks early.

Despite the results from the CISS Workforce Survey, stakeholder views on this issue were mixed. Consulted stakeholders from the justice sector provided an average score of three out of five on whether CISS has enabled earlier identification of risks to child wellbeing and safety. Additionally, stakeholders from the justice sector indicated that CISS has not necessarily enabled earlier identification of risks to child wellbeing and safety. These stakeholders and others also highlighted that there is no ability to track outcomes following responding to a request for information. That is, there is no capacity for an ISE responding to an information request to understand whether the potential risk of harm to a child was addressed after information regarding the child was shared.

“I can see how [CISS] may inform identification of risk across services but not necessarily at an earlier point. I think that lies in the struggle with proactively sharing information.” – Phase One stakeholder

This stakeholder feedback implies that further collaboration and communication between ISEs has the potential to support early identification of risks of harm to children. In the CISS Workforce Survey, the majority of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that there is more collaboration and communication between service providers as a result of CISS (64 per cent), indicating that the CISS implementation activities undertaken to date that focus on promoting cross-sector collaboration (e.g., CISS Change Program) may support achieving this objective (n=330). A survey respondent noted that CISS’ impact on children has been observed “indirectly through services feeling more equipped with knowledge about the children, feeling able to support them better.” This highlights an indirect yet positive impact of CISS on children by emphasising the enhanced capabilities and knowledge of service providers. This heightened awareness allows service providers to offer more effective and tailored support, potentially leading to improved outcomes for children. As such, there is value in CISS not only facilitating information sharing, but also in fostering a more informed and responsive environment that ultimately benefits the wellbeing of children involved with these services.

3.3.3 ISE consideration of the views of children and families

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcome SO6.

Available data is limited regarding the extent to which children and families are consulted with prior to or following the disclosure of their information through CISS. This consultation is a principle underpinning Part 6A of the Act – it must be recorded under the record keeping requirements and it is a feature of CISS training and guidance. In some instances where service providers did engage with families, some positive insights were shared.

“Where services have had open discussions with children and families about transparent information sharing, [CISS] is an enabler. Where services have not had open discussions, it is a barrier.” – Phase Two stakeholder

However, further evidence is required to understand the extent to which implementation activities have promoted visibility of these objectives and made progress towards these intended outcomes.

It should also be noted that consent is not required for ISEs to share information under CISS. However, in some cases where information sharing did not take place, discomfort about sharing without consent was a factor.

Additionally, the extent to which ISEs have consulted relevant person(s) prior to sharing information under CISS and any impacts of these consultations on proceeding or refusing to share information is only known at the ISE level due to the record keeping requirements under CISS.

The decision to share information for child wellbeing and safety will not always be straightforward for practitioners. There is an opportunity to further improve clarity regarding expectations about consultation before sharing information and the related issue of consent. Equally, the over-riding benefits of information sharing in most instances and the need to encourage information sharing is acknowledged. The development of additional case studies tailored to workforces and sectors may help support and build confidence in practitioners to make choices within this decision-making framework and further enhance understanding of the purpose and benefits of CISS.

3.3.4 Commitment to child wellbeing

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcome MO8.

Professionals prescribed as ISEs under CISS are inherently expected to have a strong commitment to promoting child wellbeing and safety. However, this Review was not able to collect concrete evidence to confidently attribute the facilitation of this commitment to CISS. While CISS plays a crucial role in facilitating information sharing and collaboration, evidence from stakeholders consulted in this Review suggests that the commitment to child wellbeing and safety among service providers may be driven by broader factors, including professional standards, organisational culture and individual judgement. As a consequence of the diversity of sectors and workforces operating within CISS, there is significant differentiation between these broader driving factors, and thus, ISEs’ interpretation of CISS will vary. This further implies a need for localised practice guidance and reflection to be developed, coupled with effective support from the Department as the entity with overall responsibility of CISS.

3.3.5 Participation in child information sharing

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcome SO7.

The Two-Year Review found that the reporting and recording by ISEs engaging in information sharing were inconsistent, with only some organisations providing this data, and in varying formats. Stakeholders consulted in the Two-Year Review indicated infrequent use of both schemes, with slightly greater use of FVISS. Data from the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing revealed that Victoria Police, family violence services, mental health services, Department of Justice and Community Safety – Youth Justice, and hospitals were the primary requestors through CISS. In contrast, the Department received significantly fewer CISS requests, with the majority coming from the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, Child First, Victoria Police, and government schools. The Two-Year Review found that early childhood education, school, and community services sectors showed a proactive focus on child wellbeing and were more experienced with CISS. Local government representatives reported an increase in referrals due to information sharing, leading to a substantial time commitment for processing information sharing requests.

This Review considered data relating to the volume of information sharing activities from central information sharing teams where it was available. The datasets from each information sharing team varied across timeframes and in granularity, such that it is not possible to produce the same summative charts or directly compare insights from these datasets. The Department and the Department of Health do not have central information sharing teams, so there is no data available to determine the volume of information sharing activities for these organisations.

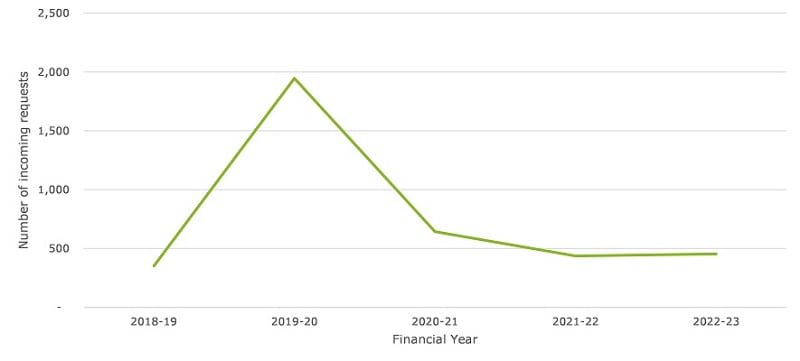

Victoria Police’s Inter-Agency Information Sharing Service (IISS) provided data on incoming requests for information under CISS from the 2018-19 financial year to the 2022-23 financial year (see Chart 3.1 below). Data under both CISS and FVISS was provided as the IISS identified that many requests made under FVISS include mention of children. For example, the IISS noted that 423 FVISS requests (six per cent of all 7,150 FVISS requests) in the 2022-23 financial year involved at least ‘one child party’. It is optional for ISEs who engage in information sharing activities under FVISS to mention children, so it is unknown how many FVISS requests involve circumstances impacting children.

It is important to note that Victoria Police’s investigative powers, which enable the agency to investigate incidents and suspected crimes (which includes requesting and sharing of information), were available to Victoria Police prior to the establishment of CISS and extend beyond those available through CISS. Mandatory reporting is a legal obligation for specific individuals or groups to report any reasonable belief of child physical or sexual abuse to child protection authorities such as Child Protection. Child Protection may, in turn, report certain cases to Victoria Police for potential criminal or civil action. During investigations into family violence, Victoria Police may encounter children who have experienced family violence and who are at risk, prompting referrals to Child Protection for further assessment. Child Protection and Victoria Police also have a Memorandum of Understanding that includes details on information sharing practices. The high frequency of police interaction with family violence matters also accounts for the higher use of FVISS by Victoria Police compared to CISS.

Additionally, the Reportable Conduct Scheme mandates that certain organisations respond to allegations of child abuse or other child-related misconduct involving their workers and volunteers. These organisations are required to notify the Commission for Children and Young People of any such allegations, with the Commission independently overseeing the organisation's responses to ensure appropriate actions are taken.

As such, it is unlikely that Victoria Police will utilise CISS for investigative purposes given there have been processes and mechanisms in place to do so since before CISS’ establishment. This reflects a broader context where law enforcement agencies may resort to established frameworks, such as the Reportable Conduct Scheme, when seeking information related to child wellbeing and safety from organisations such as ACCOs, potentially bypassing CISS in certain situations. Regarding the risk of misusing data, CISS has established criteria which enable ISEs to refuse a request for information if they determine that the request may lead to the misuse of data.

In practice, Victoria Police does not limit its information sharing requests to being made through the centralised information sharing team, so as to enable its members to quickly request information from other agencies as required and in a timely manner, including over the phone.

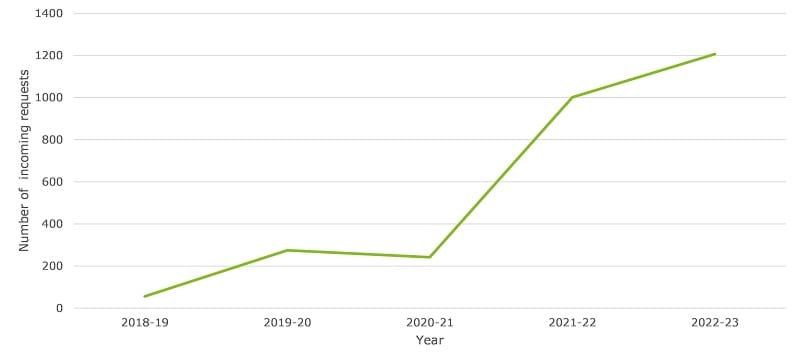

The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing’s Information Sharing Team (IST) provided data outlining the volumes of requests for information it received between 2018 and 2023 (see Chart 3.2 below). This data includes requests received under CISS only and requests received under both CISS and FVISS.

The IST provides responses to requests to historical Child Protection information. The IST refers information sharing requests for completion to Child Protection when they are open and working with the family at the time of the request. The IST supports development of the response and otherwise follows up completion of requests with Child Protection. The IST also works with other prescribed Department of Families, Fairness and Housing workforces.

The IST also advised that incoming requests may pertain to multiple people. For example, information about more than one child may be sought in one consolidated request. The IST has separately provided data on the numbers of children on a quarterly basis to the Department of Education.

The data shows that the volumes of information sharing requests under both CISS and FVISS, and CISS only have steadily increased since CISS’ implementation. Since 2019, there have been greater volumes of requests under both CISS and FVISS than under CISS only.

The most common requests of information made to the IST were from:

- Victoria Police

- family violence services

- mental health services

- Department of Justice and Community Safety – Youth Justice

- hospitals.

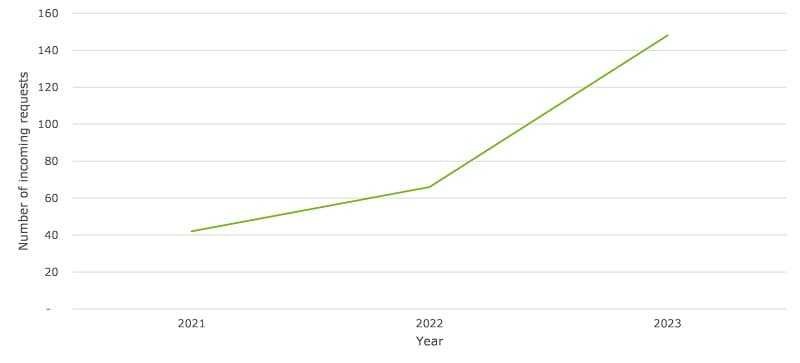

The Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (MCV) reported volumes of incoming requests for information to its Central Information Sharing Team since it voluntarily became an ISE under CISS in 2021 (see Chart 3.3 below). The total volumes of requests under CISS have increased each year, although this trend was also observed in the volume of incoming requests under FVISS during the same period. There is a significantly greater volume of incoming requests under FVISS than CISS, with incoming FVISS requests ranging between approximately 28,000 and 49,000 per year. This difference in volumes of incoming requests to MCV under FVISS compared with CISS is likely significantly driven by its role in the justice service system.

The Department of Justice and Community Safety reported volumes of information sharing activities by its central units in quarterly CISS Implementation Status Reports. While some ISEs were reported to have made and received material volumes of requests for information under CISS and/or FVISS, volumes for each of these ISEs were generally reported at least quarterly to the CISSC, with some instances of additional reporting where volume data was available. Those volumes were generally low (less than 20 per quarter), however this does not necessarily reflect low information sharing activities as the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing data indicated that Youth Justice (one of the central units) was one of the largest requestors to Child Protection.

The machinery of government change that moved Births, Deaths and Marriages (BDM) from the Department of Justice and Community Safety to the Department of Government Services resulted in a period in early 2023 where BDM was unable to share information under CISS. These factors detract from the extent to which the volume data can accurately reflect information sharing activities.

3.3.6 Quality, timely and appropriate child information sharing

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcomes SO7, SO8, SO9, MO11.

In the CISS Workforce Survey, the majority of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that:

- CISS makes it easier to share and access information to support a child’s wellbeing and safety (66 per cent, n=330)

- CISS allows for better support to be delivered to the children in their care (57 per cent, n=330)

- CISS improves their organisation’s ability to promote child wellbeing and safety (75 per cent, n=330).

Views were more measured in interview consultations with stakeholders. Phase One and Phase Two workforces across local government, education, and justice agreed and understood how increased information sharing under CISS could promote the safety of children but had limited understanding on how it promoted the wellbeing of children.

Overall, the CISS Workforce Survey and consultations both found that a broad range of sectors and stakeholders across Phase One and Phase Two workforces are sharing and accessing confidential information using CISS when it promotes a child’s wellbeing and/or safety. Compared to the information sharing landscape available to these professionals prior to the introduction of CISS, this is a net increase in information shared for this purpose. In particular, the prescription of universal education, early childhood and health workforces in Phase Two has significantly increased visibility of these issues, and the majority of these groups (65 per cent) considered that CISS improves their ability to share information to promote children’s wellbeing and safety (n=243). This is a critical indicator of CISS’ success.

However, there is limited evidence to definitively establish the extent to which CISS has facilitated quality, timely and appropriate child information sharing. This arises from the deliberate design intention of CISS to reduce the compliance and reporting burden on ISEs so as to encourage information sharing. For example, a stakeholder from the health sector noted that it is difficult for them to describe any impacts of CISS on children, as their use of CISS is typically focused on informing risk assessments and safety planning. As such, it is generally not possible to observe the outcomes or impacts of decisions flowing from information sharing.

The timeliness of responses to requests to share information is difficult to measure due to there being many ISEs and an unknown volume of information sharing activities due to CISS’ decentralised design. While there is limited data on the timeliness of responses to requests for information, some larger ISEs have developed central information sharing teams which collect data on requests for information. These teams and any internal measurements of timeliness in regard to information sharing are voluntarily generated, and are not required under the Act, Regulations or Ministerial Guidelines. This data has been analysed to provide some indicative insights into the timeliness of information sharing activities among these ISEs.

Victoria Police noted that the IISS’ business objective is to respond to requests for information within five business days and that the current average turnaround time for information sharing requests under both schemes was one to two days. The IISS’ response times are influenced by factors including periodic freezes on staff recruitment to Victoria Police, staff parental leave and vacancies, and growth in service demand.

Incoming requests to the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing’s information sharing team are allocated and given an internally imposed due date of five business days from the date of receipt for response. Since October 2022, the information sharing team has captured data including the date the requests were received, their nominated due dates and the date the requests were completed. A significant proportion of incoming requests are transferred to the appropriate channel (e.g., approximately 30 per cent of incoming requests for information relate to a child known to Child Protection). These requests are transferred to the appropriate Child Protection Practitioner for response.

Conversely, some stakeholders from ISEs that did not have central information sharing teams noted that responding to requests for information under CISS could be time-consuming.

“One barrier to using CISS is the time spent responding to applications, particularly as we don't receive many and have to spend considerable time refreshing ourselves of the appropriate responses and procedures.” – Phase Two health professional

“It's time-consuming dealing with information sharing requests. Sometimes the back and forth can take up half your day. It's a huge time burden and it's not accounted for. Within the database, there is no way to capture how much time is spent on information sharing.” – Phase Two local government professional

The demonstrable impact of CISS on the appropriateness of child information sharing has broadly remained the same over time. The Two-Year Review found that the percentage of designated workforces reporting occasional refusals of incoming information requests notably decreased by 11 per cent, declining from 46 per cent to 35 per cent. In contrast, the proportion of those stating they never refuse such requests saw a substantial increase of 17 percentage points, rising from 22 per cent to 39 per cent. In this Review, 35 per cent of respondents to the CISS Workforce Survey indicated they never refused a request for information through CISS, with 17 per cent indicating they occasionally refused a request (n=330). The common reasons reported by CISS Workforce Survey respondents for refusing a request for information include that insufficient information accompanied the request, making it challenging to ascertain whether sharing under CISS is permissible, or that thresholds or criteria for sharing were not met.

3.3.7 Improved service system coordination aligned to the interests of children and their families

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcomes MO1 and MO7.

The Two-Year Review found that CISS has led to increased collaboration and coordination among ISEs at various levels. For example, different peak bodies joined working groups to forge new relationships and develop shared resources for their respective workforces. It was also evident that organisational collaboration was encouraged through CISS, with some ISEs implementing co-location to facilitate information sharing between traditionally separate organisations. Face-to-face training opportunities allowed participants from various sectors to interact, build relationships, and gain insight into different approaches to cases. Additionally, virtual platforms were reported to improve the efficiency of state-wide training and professional development, particularly in regional areas.

In this Review, stakeholders reiterated the importance of service system collaboration and coordination among ISEs. CISS Workforce Survey respondents reported an understanding that proactive sharing of information in the interests of children’s wellbeing and safety is a key consideration of CISS, through the enablement of collaboration among service systems. For example, a stakeholder noted that, “CISS provides the opportunity for collaboration between services in the best interest of the child ensuring services supporting families have up to date information regarding child health and development and awareness of any flags regarding the family relationship.” CISS has reportedly facilitated collaboration between services, which has allowed ISEs to become familiar with workers from other agencies, thus leading to the streamlined provision of care for children. Feedback was also received in relation to the understanding that receiving information is one aspect of keeping children safe, however there should be equal emphasis on collaboration to ensure that interventions are tailored and meet the needs of the child.

“CISS has been very helpful to ensure that everyone is on the same page and working for the benefit of the child's wellbeing and development.” – Phase Two early childhood professional

It is evident that stakeholders have furthered this understanding of the importance of collaboration and coordination into practice. Findings from the CISS Workforce Survey indicate that CISS has fostered improved communication and collaboration between service providers, with 74 per cent of respondents expressing a favourable response (n=330). Notably, Phase Two ISEs reported favourable outcomes (77 per cent, n=243) in a higher proportion when compared to Phase One ISEs (68 per cent, n=87). Moreover, 11 per cent indicated they had shared information proactively and a further 50 per cent indicated they had shared information both proactively and in response to other agencies or individuals (n=330).

Stakeholders from the family violence (Phase One) and health (Phase Two) sectors highlighted the perceived positive impact of CISS on coordination and collaboration within service systems. Importantly, a stakeholder not prescribed as an ISE under CISS reported that: “[CISS] has enabled professionals working with children to work together on shared goals and to have a shared understanding of the family’s needs. It has enabled services to work together to provide the services the child or family need in a coordinated manner.” This observation by a non-ISE demonstrates the facilitation of a broader cultural shift towards collaboration enabled by CISS, extending its benefits beyond the prescribed ISEs and promoting a more holistic and effective approach to child wellbeing and safety.

It should be noted that 16 per cent of CISS Workforce Survey respondents had only shared information in response to requests from other agencies or individuals, and 20 per cent had not shared information under CISS (n=330). These results align with the fact that the majority of respondents who had not shared information under CISS were from Phase Two workforces, constituting 25 per cent of Phase Two respondents (n=243). However, it should be noted that these results do not directly comment on ISEs meeting their legal obligations as explored in Section 1.3.4, and rather provide some insight on CISS’ progress against improved service system coordination. Cultural shift that maximises the impact that CISS can have on better outcomes for children will be realised when services are systematically and proactively sharing information or requesting information, which they may do under CISS. As such, it should be noted that while significant progress has been made to demonstrate improved collaboration and coordination to date, further work is required to ensure that this is consistently and systematically demonstrated (particularly for Phase Two ISEs who have not shared information under CISS at the time of this Review).

3.3.8 High human service job satisfaction

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcome MO5.

Assessing the precise impact of CISS on human service job satisfaction is challenging. Job satisfaction in human service environments is influenced by a multitude of diverse factors, including organisational culture, work environment, support systems, service outcomes, employment conditions and individual motivations. While CISS may play a role in improving service coordination and information sharing (see Section 3.3.7) in a way that gives employees the capacity to influence outcomes for children, it is just one component of the broader professional landscape. The nuanced and multifaceted nature of job satisfaction makes it inherently difficult to isolate CISS as the sole driver of high satisfaction levels. Stakeholders consulted as part of this Review were not able to provide any insights into the impact of CISS on their job satisfaction.

3.3.9 Confidence and culture change in child information sharing

This section provides evidence on CISS’ progress against achieving outcomes MO6 and MO10.

3.3.9.1 ISE confidence in sharing child information

As the awareness and understanding of CISS among ISEs has improved (see Section 3.3.1), professionals’ confidence in using CISS also appears to be improving and is higher among Phase One workforces. CISS Workforce Survey findings reveal that a lack of confidence was the least nominated reason Phase Two ISEs would refuse a request for information (one per cent, n=429).

Notably, no Phase One ISEs reported a lack of confidence in this aspect. Furthermore, ISEs are displaying increased confidence in sharing information under CISS, with 28 per cent stating they are more confident about sharing information under CISS compared to before CISS was introduced (n=153).

Of Phase One workers who responded to the CISS Workforce Survey, the majority had either shared and/or received information through CISS (92 per cent), which comprises a majority of the respondents who knew they were able to share information under CISS (98 per cent, n=87). While Phase One workers generally agreed or strongly agreed (80 per cent, n=87) that they are confident in their understanding of CISS, a similar proportion either agreed or strongly agreed they would benefit from more training (82 per cent, n=17). Overall, this indicates significant progress towards CISS’ short- and medium-term outcomes for Phase One workforces.

Further, 63 per cent agree and 11 per cent strongly agree they are confident in their understanding of CISS in the CISS Workforce Survey (n=330). Conversely, 5 per cent disagree and 3 per cent strongly disagree they are confident in their understanding of CISS. However, confidence to use CISS was significantly influenced by the extent of professionals’ engagement with implementation activities.

As outlined in Section 2.2.2.1, most Phase Two professionals who accessed the LMS were from the Department and their funded agencies (56 per cent, n=40,103). As such, 69 per cent of early childhood professionals (n=51) and 81 per cent (n=133) of education professionals reported a high confidence in their understanding of CISS. This was supported by stakeholder views.

“[CISS] has resulted in increased confidence to have conversations within working teams and across service providers.” - Phase Two education professional

Health workforces across Phase One and Phase Two equally reported a high level of engagement with implementation activities (see Section 2.2.2 for more information) and had reported a high level of confidence in the CISS Workforce Survey (64 per cent, n=70).

Phase Two workforces, who predominantly work in education, including early childhood, and community health, reported more confidence in their ability to share information about the wellbeing of children under CISS compared to Phase One workforces. For example, a stakeholder in the education sector noted, “early childhood education uses [CISS] for the child’s wellbeing on their background or the family to provide early intervention and care to connect and see if there are deeper issues with the child or the family,” whereas another Phase One justice stakeholder expressed discomfort with the wellbeing thresholds and did not know when to share information for wellbeing concerns. This may be because Phase Two working environments operate with a stronger and more definitive care, health, and wellbeing lens compared to Phase One workforces, which operate in more reactive environments that look to ensure the safety of children in danger. There was a view in workforces from statutory services such as child protection and justice that wellbeing is a somewhat vague concept which may lead to uncertainty regarding information sharing.

“Everyone views safety, wellbeing and risk so differently. There may be changes in individual organisations’ practices, but not across the services at large.” - Phase One justice stakeholder

Confidence to share information through CISS continued to mature for other professionals based on their engagement with implementation activities. All of Phase One justice workforces either agreed or strongly agreed they would benefit from more training on CISS, which impacted their confidence to share information under CISS. However, this confidence improved with more engagement. A Phase Two stakeholder in child protection noted, “it took a while for staff to build up confidence to be okay to share. There was still hesitancy at the start but as time has progressed, [information sharing] has become a fluid experience that it was originally.” Additionally, another Phase Two peak body cited, “uptake [with focus groups] was low and confidence with CISS was low. Now 18 months later, the confidence is low but building and services have a better understanding of the scheme than they used to.”

“Workers experience anxiety around privacy and confidentiality concerns and do not understand the CISS’ process, translation of policy into practice and understanding of child focus practice.” – Phase Two early childhood professional

The relevance and depth of training materials (outlined in detail in Section 2.2.2.2) also impacted confidence to share information under CISS. A Phase One child and family service stakeholder reported, “the e-learns can be quite brief. The feedback is that those service providers don't feel comfortable and they need more training.”

3.3.9.2 Culture change among ISEs in child information sharing

The Two-Year Review found that CISS has played a crucial role in fostering shared responsibility for child wellbeing and safety among organisations. While there was a significant positive shift in attitudes and cultural changes within these entities, the effectiveness of information sharing remained unclear. Workforces expressed a willingness to share, but the lack of uniform understanding on how to robustly record and share information posed obstacles. There was a recognised need for further efforts to enhance the capabilities and capacities of ISEs. While CISS had heightened awareness, there was a call for a more substantial practice uplift to bridge the gap between intent and practical implementation, ensuring that shared responsibility translates into tangible actions.

In this Review, stakeholder consultation themes evidenced a positive shift in culture change from establishment of CISS. Stakeholders, particularly those from the family violence, early childhood, and local government sectors, noted they believe there has been a shift in culture change regarding information sharing that has been facilitated by CISS. This is of particular importance, given some workforces were previously in risk averse environments regarding information sharing.

However, further work is required to ensure that this culture change is implemented consistently across all workforces and in ways that translate to measurable improved outcomes. Although there is limited evidence to suggest that culture change has been driven across all systems at this point, this consistent insight from many stakeholder groups suggests that there is good progress in the understanding of CISS and achieving systemic change over time since the Two-Year Review.

“We’ve seen pockets of positive change, but I think that the significant work [around] practice and culture change is [still] ahead” – Phase One child and family services professional

3.3.10 Monitoring the adoption of CISS

3.3.10.1 Maintenance of information sharing records

In preparation for CISS, ISEs had revised their record keeping policies and processes with the aim to ensure compliance.50 However, the Two-Year Review highlighted that record keeping practices were mixed at the time with higher compliance rates when ISEs received requests compared to when they were requesting information or responding to a complaint. Most organisations surveyed at the time of the Two-Year Review indicated that they were not recording all of the required information under the Regulations. Since the Two-Year Review, the Department has established some further guidance material to support compliance with record keeping processes. For example, since the Two-Year Review, the Department has developed the ‘Example record keeping form’51 and the ‘Tips for information sharing and record keeping’ 52, which are accessible online. Stakeholders indicated this guidance has made the process for record keeping more efficient and streamlined.53

Some larger entities that are either ISEs, or have oversight roles of ISEs such as the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing have established centralised teams within their organisations to manage sharing and requesting of information, including record keeping. For information sharing requests relating to a child known to Child Protection, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing information sharing team directs those to the appropriate Child Protection Practitioner and undertakes follow-up activities with that Practitioner where appropriate. Through consultation with the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, this Review understands that the centralised team provides more streamlined and efficient processes for information sharing, and in some cases also involves ad hoc upskilling where the team becomes aware of instances of misunderstanding of obligations under CISS. This team is designed to complement (rather than replace) information sharing practices among individuals within those ISEs.

3.3.10.2 Monitoring the adoption of CISS

There is potential for data captured through Child Link and/or recorded by ISEs to provide government with an understanding of the extent to which CISS is being utilised across the state. At this point in time, the Department receives and reviews data relating to the number of information sharing requests on a quarterly basis through reporting from key government agencies.54 Beyond this data, the Department does not maintain oversight of information sharing requests made or received by other ISEs. This approach has been intentionally chosen to minimise reporting burden and double handling of information across government and ISEs. However, it also limits government’s ability to understand the extent to which information is being requested and shared across ISE workforces.

Some stakeholders in the education and early childhood sectors interviewed expressed a desire for increased reporting, monitoring and oversight of information shared under CISS. Stakeholders considered this a necessary action to either measure the volume of CISS’ use as a means of informing its effectiveness, or to act as a safeguard against inappropriate and deliberate misuse of CISS. On the other hand, some public sector and education stakeholders noted that their respective organisations have introduced comprehensive information sharing documentation and record keeping requirements, and that these requirements varied significantly. However, the extent of processes imposed by ISEs can vary from organisation to organisation and be influenced by organisational size and resourcing.

It is acknowledged that any such process would impose a further reporting burden on ISEs, which are often resource-constrained workforces experiencing high levels of staff turnover (see Section 2.3.2.1). A balance is required to ensure that any monitoring and reporting activities undertaken by departments and agencies also consider the intent of CISS without undermining its intended outcomes.

3.3.1.1 Conclusion

Overall, this Review found that CISS has made considerable progress against achieving its short- and medium-term outcomes relevant to understanding of CISS, cooperation and collaboration across services, and confidence in sharing information related to the wellbeing and safety of children. Due to the intentional design feature of CISS, monitoring the adoption of CISS relies on data recorded by ISEs and the Department’s regular oversight of data collected by ISEs is limited to key government agencies. As such, this has limited the ability to demonstrate the extent to which CISS has been adopted across the relevant workforces and its impacts on broader child wellbeing and safety outcomes.

3.4 To what extent are there early indicators of the reform achieving its long-term outcomes?

This section considers the long-term outcomes in Table 3.2 below.

Table 3.2: Relevant long-term outcomes to Chapter 3

| Program | Logic Model outcomes |

|---|---|

| LO5 | A dominant professional practice ethic among ISEs of shared responsibility. |

| LO6 | Child and family service systems are effective, efficient, responsive and agile. They reflect a collaborative approach to support and share responsibility for children’s wellbeing and safety. |

| LO7 | Child wellbeing and safety is embedded in organisational leadership, governance and culture. |

Source: Deloitte Access Economics.

Note: Refer to Appendix A for more detail on the Program Logic.

It should be noted that, at this Review point in the implementation cycle, it is not expected that CISS will have achieved these long-term outcomes; rather, this section provides evidence on the extent to which CISS is on track to achieve these outcomes over time. Successful outcomes are likely dependent on a number of factors, including further implementation of CISS and improved engagement with the reforms across a wider range of providers. There should also be recognition of the longer timeframes required to achieve long-term child wellbeing and safety outcomes, and factors other than child information sharing that are likely to also affect the achievement of these outcomes.

3.4.2 Shared responsibility for child wellbeing and safety among ISEs

This section provides evidence on the extent to which CISS is on track to achieve outcomes LO5 and LO7.

In the Two-Year Review, it was noted that positive signs of impact were evident in terms of fostering shared responsibility for child wellbeing and safety. A notable cultural shift was observed among various ISEs, indicating an increased awareness of the importance of shared responsibility in safeguarding children's wellbeing and safety. This shift resulted in a greater willingness among ISEs to collaborate with other organisations and services with the common goal of enhancing child wellbeing and safety. Stakeholders from the Two-Year Review highlighted the growing willingness of different parts of the organisation to work together, underscoring a deeper understanding of the significance of child safety. Moreover, for those already aware of shared responsibility, the implementation of CISS further reinforced and operationalised this collective commitment.

In this Review, it is apparent that this has continued to develop, with a widespread perception that CISS is a positive force in contributing to child wellbeing and safety efforts. For example, CISS Workforce Survey respondents reported that generally, staff at their organisation are aware of their legal responsibilities when sharing information through CISS (56 per cent agree and a further 16 per cent strongly agree, n=330). Nonetheless, it should also be noted that one-fifth of CISS Workforce Survey respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with this statement, indicating that there is still a segment within these workforces who may require further clarification or education regarding their legal obligations under CISS. This includes strengthening the understanding and engagement of all ISEs in their shared responsibility, which should in turn foster a comprehensive and unified approach in safeguarding child wellbeing and safety across various sectors.

“[CISS] fosters a culture about responsibility as to how you handle the child into the ‘next relationship’ as well (i.e., the individual child and the next entity they deal with).” – Phase One Commissioner

The effectiveness of CISS in promoting child wellbeing and safety can be improved through strategic alignment within the broader wellbeing and safety reform context in Victoria. For example, continued aligned implementation of CISS and FVISS is crucial for optimising the impact of information sharing as a whole. Further effort to ensure ISEs understand which scheme is the most appropriate to use in different situations could reduce the confusion among some stakeholders and increase efficiency in the use of information sharing (see Section 3.3.1).

3.4.3 Effective, efficient, responsive and agile service systems based on collaboration

This section provides evidence on the extent to which CISS is on track to achieve outcome LO6.

Considerable progress has been made in terms of building awareness and understanding (see Section 3.3.1) and facilitating collaboration and coordination among ISEs (see Section 3.3.7). However, it should be noted that CISS is still maturing in terms of facilitating a consistent and systematic approach to information sharing among all ISEs. As such, there is limited evidence to suggest the extent to which CISS is on track to achieve effective, efficient, responsive and agile service systems at this point, given these are reliant on a more sustained implementation effort to be embedded (see Section 2.2.6). Additionally, achievement of these outcomes cannot solely rely on CISS for their success. It is important to acknowledge that child and family services operate in a dynamic environment. The risk landscape continually evolves, and service systems must adapt accordingly. While CISS is a critical enabler of ensuring child wellbeing and safety, the ability of service systems to be effective, efficient, responsive and agile hinges on a multitude of factors, including adaptability to the ever-changing landscape within child and family services.

3.4.4 Long-term wellbeing, participation in universal services and early intervention

This section provides evidence on the extent to which CISS is on track to achieve outcomes LO1, LO2, LO3 and LO4.

The extent to which CISS is on track to achieve long-term outcomes relevant to child wellbeing, participation in universal services, and early intervention, is unclear at this point. The type of data that would be needed to understand the impact of CISS on these outcomes is not currently being collected by any agency and it has not been possible for this Review to obtain such data. This is a function of the current design of CISS and its limited reporting requirements as discussed above.

3.4.5 Conclusion

While it is not expected that CISS would have achieved its intended long-term outcomes in the timing of this Review, it is noted that there are early indicators of CISS achieving positive impacts over time, particularly relating to facilitating a cultural shift among ISEs towards shared responsibility for child wellbeing and safety. However, there is less evidence to determine the extent to which CISS is on track to achieve positive outcomes directly relevant to child wellbeing and safety, given there is limited data collected at this point pertaining to the achievement of such outcomes.

3.5 Is there any evidence of negative impact of the reform on diverse communities and communities experiencing disadvantage?

3.5.1 Cultural safety considerations

3.5.1.1 Consultation with Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations

It is established that Aboriginal communities and children experience some of the highest levels of vulnerability which have the largest effects on wellbeing and safety. Complex community and family needs often intersect with a need for cultural safety in their engagements with systems of government. The Department conducted a series of consultations with relevant ACCOs prior to the introduction of CISS, in recognition of the nature of Aboriginal communities as a core audience and intended beneficiary of CISS. The Department advised that those ACCOs who were consulted were supportive of the VCIS Reform.

3.5.1.2 Provisions within the Act, Ministerial Guidelines and practice guidance

In recognition of the potential risks involved with information sharing involving communities experiencing disadvantage or vulnerability, government has established relevant provisions and guidance within the Act, the CISS Ministerial Guidelines and CISS practice guidance.

The Act, the CISS Ministerial Guidelines and practice guidance established by government have identified clear cultural safety safeguards identifying the key risks that should be managed.

As defined in Part 6A of the Act, CISS is intended to “promote the cultural safety and recognise the cultural rights and familial and community connections of children who are Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander or both.”

The CISS Ministerial Guidelines define terms such as ‘good faith’ and ‘reasonable care’. Specifically, individuals are considered to act in good faith and with reasonable care if they:

- share information in accordance with their obligations, functions and authorisations

- intend for the information to be shared for the purpose of promoting the wellbeing and safety of a child and not for another purpose; and

- do not act maliciously, recklessly or negligently when exercising their power to share information.55

Further, the Minister for Housing, Disability and Ageing’s second reading speech outlined a clear commitment to cultural safety through the VCIS Reform, including:

“Similarly, we know that when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are supported early to develop a strong cultural identity, their educational and developmental outcomes greatly improve. Interventions that build children's social and emotional skills and confidence in their abilities have significant long-term benefits for those children, and society more broadly.”56

The Department has also established the CIS Fact Sheet and the CIS Flyer which reflect the principles provided within the Act.57,58 For example, the Department has emphasised that “information cannot be shared unless [it is] being used to promote the wellbeing and safety of children”. The CIS Fact Sheet also provides some short examples of how information should be shared and requested under CISS.

This Review acknowledges that at this time there is limited available data on the extent to which there have been instances of non-compliance with these cultural safety practices. The Department has indicated there have been no reports or complaints of any such instances. Equally, under the current Scheme design, such an instance may not be detected and may not become known to the Department or any other authority.

3.5.1.3 Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations perspectives on CISS

Consultation with ACCOs for this Review revealed there is a good level of general awareness of CISS, however there were varying levels of understanding regarding details of the Scheme and how it was differentiated from others (FVISS or MARAM). There was limited evidence of formal information sharing activities under CISS. However ACCOs did advise that it is common for them to request further information of ISEs regarding the Aboriginality of children or families who have been referred to their service. This reflects that while a child or family may be referred to an ACCO, there is often a lack of accompanying documentation (proactive sharing).

ACCOs were generally familiar with CISS templates that have been developed by the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing for use across the child and families sector. The ACCOs consulted consider there is an opportunity to review these templates and other documents relating to CISS to ensure their cultural appropriateness and usability (e.g., the suggestion for CISS documents to be accessible online to minimise the administrative burden on ISEs).

There was a clear emphasis from ACCOs on the importance of information sharing being conducted in a culturally safe manner. To ensure CISS promotes cultural safety, ACCOs are often called on to facilitate cultural safety training for other public and related services, however these are not specific to the context of information sharing, and often done as a community service, without funding. As such, ACCOs advised that additional resourcing should be provided to enable cultural safety training with a focus on information sharing.

ACCOs highlighted a desire for CISS to embed self-determination for Aboriginal community and people in its goals and application, as community members expressed the need to be informed about things affecting their children, including how their information is shared. ACCOs all emphasised the value of CISS as a way of strengthening visibility and their capacity for tailored care of children and community, noting that the capacity to better understand a child’s experience with health, education and the justice system remains a shared benefit for the child and community. Some ACCOs indicated that they hope increased collaboration with Victoria Police and the justice system in particular, will allow the community to realise better outcomes and facilitate greater trust between ACCOs and the justice system.

Additionally, peak bodies in the ACCO space highlighted that they were often called on by the ACCOs to provide support for the rollout of VCIS programs, including CISS. They pointed out that they are the best placed to prepare community level 'model resources' and best practice and in some instances they are establishing best practice tools for their services that could usefully assist with CISS implementation. Their capacity to provide this support is limited because they do not presently receive funding for CISS implementation. There is an opportunity for CISS and ACCOs to work together in considering whether ACCOs could be resourced to provide this support.

3.5.2 Specific considerations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, culturally and racially marginalised families, and families with additional needs including mental health and disability

Due to the size of the population subject to CISS (i.e., all children in the state of Victoria) it was necessary to design CISS to have broad reaching application. However, designing a scheme to be used in a “mainstream” capacity brings with it risks that those who have differing needs to the population at large, may have a different experience of CISS than was intended in the design.

To address this potential risk, efforts were undertaken to engage with a wide range of stakeholder groups in planning for CISS. A consultation paper was distributed to over 300 government and community stakeholders on the proposed legislative model for Child Wellbeing and Safety Information Sharing. This included representatives from the health sector, the community services sector, Aboriginal organisations, family violence organisations, regional organisations and unions.

Following the consultation paper, five key stakeholder workshops were convened. Issues tested by the consultation included:

- the extent of challenges with the current legislative system

- the principles that should guide information sharing

- exploring the proposed model for reform, in particular testing whether (i) a ‘concern’ threshold should be introduced; or (ii) a ‘non consent’ or ‘consideration of consent’ model should be adopted

- application (i.e., the ‘prescribed entities’ within scope)

- whether any exemptions should be permitted to sharing information

- how the Child Link proposal may support child wellbeing and safety information sharing.

In consultation for this Review, it was reported by the Department that there was broad endorsement of the proposed changes by stakeholders through this process, including by Aboriginal organisations.

The Two-Year Review sought stakeholder feedback in relation to “diverse and disadvantaged communities” however, with the exception of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the Review found there was an insufficient volume of feedback to allow conclusions to be drawn.

Nonetheless, the Two-Year Review made two recommendations with regard to diverse and disadvantaged communities: recommendation 10 that CIS Scheme partner government departments consider the adequacy of the current minimum record keeping requirements of the CIS Scheme, including as they inform the role of the CIS Scheme in responding to the needs of diverse population groups; and recommendation 11 that CIS Scheme partner government departments engage diverse and disadvantaged groups through sector and advocacy peak bodies and ISEs, to understand any specific barriers to the implementation of the CIS Scheme and use these findings to assist ISEs to overcome these barriers.

While the Victorian Government supported recommendation 11 in full, recommendation 10 was only partially supported, “Government does not support changes to the record keeping requirements as specified in the Ministerial Guidelines, but is however committed to simplifying the process of information sharing and record keeping, and to streamlining existing data collection for monitoring and reporting purposes where possible”. Implications of record keeping are further explored in Chapter 4.

This Review sought to understand the impact and potential negative consequences of CISS being experienced by a range of stakeholder groups. This Review did not pre-determine groupings of stakeholders, but through the consultation process, some specific groups were identified for whom specific concerns were articulated. This is not to be taken as an exhaustive list of all communities that may have experienced unintended impacts or negative consequences of CISS.

The groups identified were:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families

- culturally and racially marginalised families

- families with additional needs including mental health and disability.

These groups are considered separately below so as not to conflate their experiences with CISS, however it is acknowledged that they are not like-for-like in terms of their identification, nor are they mutually exclusive to one another.

Furthermore, this Review respects the unique rights and responsibilities of Aboriginal communities as the First Peoples of the lands across Victoria and acknowledges that it is not appropriate to define their cultural or community needs and aspirations in relation to either diversity or disadvantage. For the purposes of producing a point of comparison with the Two-Year Review and consistent with this Review’s lines of enquiry, this Review sought to include Aboriginal community perspectives.

3.5.2.1 Information sharing risks for Aboriginal children and families in Victoria

It is important to consider CISS in the context of the political, social and cultural systems with which it intersects. CISS is an enabler of information sharing, but the lived experience of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is that the information being shared about them is not in the interest of their care, but in the interests of state authority and control. It should be noted that CISS enables ACCOs to receive information about Aboriginal children from universal services, enabling them to do their important work as part of a children’s service system that better serves Aboriginal children, highlighting benefits of CISS for these communities. However, cultural safety issues, including systemic racism, have been highlighted across the many forms of ISEs prescribed under CISS – in justice,59 education,60 health and other forms of care.61 In the absence of sufficiently culturally informed people and practices embedded in these ISEs, there is a risk that information may be sought, shared and interpreted in a way that perpetuates rather than minimises harm for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and families in Victoria.

In Victoria, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children come into contact with child protection at eight times the rate of non-Indigenous children.62 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are incarcerated in youth detention at eleven times the rate of non-Indigenous children.63 The Two-Year Review found a key barrier in the implementation of CISS expressed by ACCOs was the legacy and abiding harm of past experiences relating to services, with stakeholders acknowledging “there is still a lot of distrust and fear of children being removed as a result of information sharing.” This point in relation to CISS was also acknowledged through the FVISS Two-Year Review, noting “widespread concern that combined FVISS and CISS could lead to an increase in the involvement of Child Protection in Aboriginal mothers’ lives.”

While the Two-Year Review also stressed that CISS was aimed at increasing early interventions which would reduce rather than escalate referrals to Child Protection, it was also the case that to build trust in the new CISS would have required a significant investment in continuous education and culturally relevant resources for families, where the universal tools and materials did not appear to have been developed in consultation with Aboriginal people.