- Date:

- 31 Aug 2023

This guide outlines a range of things that should be considered in planning to rebuild after a bushfire, or in building in a bushfire prone area.

It does not advocate particular house designs, or materials to be used beyond the general principles that lead to more bushfire resilient dwellings.

Introduction

The information in these guidelines is intended to assist people who are planning to rebuild dwellings impacted by bushfire to make informed choices in planning designing and commissioning their new dwelling. It may also be of relevance for people considering how to improve the resilience of existing structures to the impact of bushfire.

Bushfires are dramatic events and the process of rebuilding, where people choose to do so, is a significant undertaking. This is because, for most, the need to suddenly get a new house built is not on their radar. Different people will move forward at different times depending on their objectives and intentions.

These guidelines are designed to help you:

- understand the rebuilding process

- think about the sorts of building, design and other professional services that you are likely to need along the way, and

- to prompt thinking about how the rest of your site is landscaped or managed.

While focused on replacement or new building, these guidelines are also relevant and complementary to existing guidelines and advice on retrofitting buildings to improve their resilience. This includes the Country Fire Association (CFA) and Victorian Building Authority (VBA) guidelines to retrofit your home for better protection from a bushfire and guides on landscaping and plant selection.

Consider the options

Designing and constructing buildings to be more resilient to the impact of bushfires is an important priority as society adapts to the impacts of more frequent and more severe bushfires.

Key considerations in creating contemporary residential structures anywhere include:

- energy efficiency and future running costs

- overall liveability

- efficient use of resources

- minimising ongoing maintenance costs

- site suitability and land stability (geotechnical) requirements particularly on steep or unstable sites, as well as

- bushfire risk and resilience and potential impact from other natural hazards.

Maintaining natural environments and environmental are also important considerations. Having an open-minded approach can optimise how structures are sited, the design of a new structure, materials used to achieve benefits for bushfire resilience as well as energy efficiency, and importantly how costs can be minimised.

In general, a building designed with bushfire in mind that suits the site and any constraints will be more cost-effective to deliver compared to retrofitting a standard design and making it more fire-resilient.

Designing a new house to be energy efficient is very complementary to the objectives in designing a fire-resilient house. Adopting an open-minded approach, embracing sustainability principles in the design of the dwelling and working with the site constraints through the design process will deliver the best results in the long term.

After a fire, it may be tempting to try and recreate what existed before. In most cases, this is not practical and if the lost house was an older structure, it would most likely not have embraced contemporary sustainable design principles. It also may not have been built to the current construction standards that your new dwelling will be required to meet.

These guidelines set out general information to help inform decisions about rebuilding after a bushfire, or for new construction in a bushfire prone area. It does not provide standard designs or set new standards, rather it acknowledges that any design solution should reflect the site and its opportunities and constraints.

There is a broad range of existing guidelines and explanatory material in the public domain in relation to requirements for building in bushfire prone areas. These can be found via the links to key information sources at the end of this document.

This guide addresses:

- key phases in the planning and building process

- siting and general locational considerations

- the structure itself

- landscaping and other site treatments

- the planning permit process

- building permits

- case studies of representative buildings in different bushfire risk settings

- key links for relevant information.

Architect Nigel Bell spent six months working with the community at Marysville, Victoria, following the Black Saturday fires in 2009.

When you’ve lost everything, he says it’s natural to want to rebuild what you’ve just lost. But it’s not necessarily the best response.

“The people who replace them quickly tend to want to fill in that hole so they build a home almost the same as the one they lost,” he says. “But it’s usually people who take their time to rebuild who will build something different and often better.”

Key phases in the planning and building process

You will often hear about the planning and building process and the need for permits and approvals. While this process concludes with planning and building permits for the development you are proposing, there can be a variety of things to consider depending on where the land is. Concept planning is fundamentally important before resolving on what you are actually proposing to do.

The need to obtain planning and building permits is an important step. There are legal approvals for the development you are proposing, and they are essential for financing. They are also important if you ever seek to sell the property either with an approved permit, or after the development is completed with a certificate of occupancy.

That's why it is important that you engage early with your local council through the rebuilding hubs early in your planning process.

The key phases in any rebuilding or new building process after a bushfire that you will likely experience include:

- concept planning

- detailed planning and approvals

- construction, and

- post completion.

Depending on where the site is some or all of the following should be considered as you proceed.

Concept phase

Bushfire planning advisers, town planners, architects and building designers can really help at this stage.

- Clean-up and removal of hazardous materials – often done through a government clean-up and make safe program.

- Site analysis, including access for emergency vehicles, slope, bushfire attack level assessment, proposed dwelling location on site, location of nearby dwellings, native vegetation and nearby and geotechnical and soil assessment.

- Identify the lowest risk site on the block - which may not be where a pre-existing house was sited.

- Assess what the clean-up process means for your site. For example, are foundations reusable or not.

- Understand your overall budget for design, construction, occupation and management of your property. This includes understanding what elements might or might not be covered by your insurance.

- Assess what specialist skills and support you might engage to help you resolve what you want to do and how you are going to go about it (architects, building designers engineers, and so on).

- Make concept plans - an open approach to working out your objectives, priorities for a new structure, conceptual design. Architects and building designers can make a huge difference here.

- Remember that there are many ways to improve a buildings resilience to bushfire. Consider that bushfire design requirements from the start are normally cheaper than retrofitting at the end of the design process.

- Engage early with your local council about your evolving concept plan and establish what approvals you need and what information you need to support making the application.

- Determine if the extent of your property title is still identifiable and consider if you need to get a boundary survey prepared. This is important where you may be proposing to build near a property boundary.

- Identify siting, access or other considerations, including an assessment of hazards on your property or within the surrounding landscape. For example, can you site the new house in a way to minimise the risk by being further away from heavy bush or forest?

- Identify where your water supply is, or what it is. For example, where will you site firefighting water tanks that are generally a mandatory requirement unless you are in a township?

- Plan where firefighting water outlets might be located.

- Assess if you have sufficient water supply if you are considering bushfire sprinkler systems as part of your design. Things to consider include the time it will need to run (at least one hour) and planning for piping where you need it?

- Assess if you can achieve vehicular access for trucks cranes or other equipment – what is the load capacity of any small bridges or other crossings that might be involved in more remote locations?

- Assess if your access is all weather capable of supporting emergency vehicles, for example, a 15 tonne truck.

- Establish overall objectives, for example, on grid or off grid, water systems, and so on.

- Consider how building features, garden walls, or earth embankments might play a part in providing radiant heat protection for parts of the structure. If your strategic plan is to stay and defend your property, where would you plan to manage defense - noting that leaving early is always the best method of ensuring your personal safety.

- Plan where gas bottles will be sited – preferably away from the house.

- Assess if previous sewerage and effluent systems or connections are still viable or require replacement, repair or renewal.

- Determine preferred construction methods and the practicality of them in terms of site access.

- Establish approximate pricing for what you are conceptually planning before you finalise your plans.

- Produce a final concept plan or plans for your whole site that establishes overall siting and design objectives and gives you confidence that you have identified all the main elements you need. Be clear about what information you need to seek planning and building approvals – this is arguably the most important step.

- Talk to the council again about your evolving concept plans.

Detailed planning and permit approvals phase

- Develop detailed plans of what will be built and finalise other supporting information as required to seek required permits and approvals.

- Lodge planning, building and any other approval applications that may be required. Engage early with your local government about your plans, timing and the essential information you will need. The council will also talk to you about advice they will seek from referral authorities including the Country Fire Association (CFA).

- Obtain final quotations and contract a registered builder if you have not already done so, appoint a building surveyor, and engage other specialists if required. Seek legal advice on contracts if you are unsure. Read the information on the Department of Transport and Planning website in relation to quotations, contracts and consumer protection.

- In almost all cases you will need a building permit for the development proposed and often a planning permit will also be required. These are legal approvals that authorise what you are intending to do and are fundamental in the building process in financing your build and insuring your building once complete.

Construction phase

- Construction phase (registered builder or owner builder).

- Mandatory construction inspections at key steps in the build (the building surveyor).

- Implement any other bushfire risk mitigation measures or conditions that are part of your planning and building permits. For example, firefighting water supply tanks if required.

- Occupancy permits (the building surveyor).

Post completion phase

- Landscaping and other site management considerations such as ensuring your defendable space is maintained.

- Your bushfire survival plan for you and your site in a future bushfire.

- Implement any other voluntary bushfire risk mitigation measures that form part of your overall approach to your site (See Sarsfield residents Kate and Anthony Nelson's blog on their site plans.

- Check to ensure that any future works do not undo the effort put into creating a more bushfire resilient house. For example, do not locate flammable things near the house or create holes that allow embers to get into the house.

- Review update and maintain your fire preparation plan.

Siting and general design considerations

Dwellings can range from a very simple structures to more complex designs consistent with council planning provisions. All can be designed to be energy efficient and fire resilient. However, there are cost benefits in adopting simple designs and thinking carefully about how and where windows and other glass are used, particularly in higher risk settings.

While it is not always possible due to block size or location, dwellings should be sited away from vegetation and be orientated on a block to face north to optimise the opportunity for good natural lighting and solar energy for winter warmth.

Sometimes you will need to balance objectives. For example, windows are generally the element most vulnerable to bushfire and radiant heat. Facing windows north may also mean you are increasing your exposure to a future bushfire. Take the time to assess whether you can achieve a better siting outcome and best balance competing objectives.

Build on a low-risk site on your block, generally to achieve less than Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) 29 exposure - so defendable space is on your property - and in your control.

It’s important to consider building form

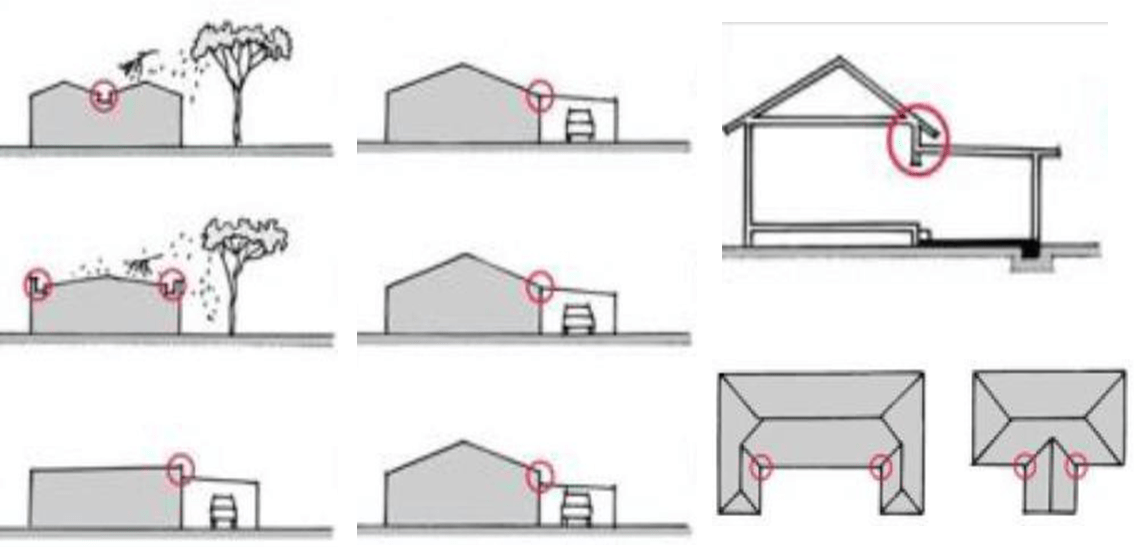

Simple shapes are best as they allow the smoothest flow of wind – and the embers born on it – over and around the house. This minimises the build-up of embers in corners where they are at greater risk of causing ignition. Roofs that minimise valley gutters are a much better idea than complex roof shapes. Box gutters should also be avoided. Avoid putting features on roofs that trap embers. Roof gutters with external brackets are less likely to trap and retain leaf material.

Features that contribute to a resilient structure include:

- siting the dwelling in a location that can achieve a BAL 29 or less exposure

- building on a slab or implement a fully enclosed underfloor

- using of non-combustible facades, cladding, windows, doors

- locating windows up off the ground

- using of paved areas rather than decks

- using steel framing for decking with a composite timber such as mod wood

- building a single story (this is preferable)

- designing and assembling for lower-level cyclonic winds that can occur during fire events.

Energy-efficient designs will be well insulated, assembled to minimise uncontrolled air leakage through the structure, and use natural controlled airflow to moderate interior temperatures. Often concrete or other mass products will be used to store and emit solar warmth.

These are complementary to achieving a bushfire resilient outcome and are low maintenance.

Any new residential building will need to embrace energy efficiency in its design as a key requirement of the National Construction Code.

Think about how a new design can minimise energy costs and be more comfortable to live in

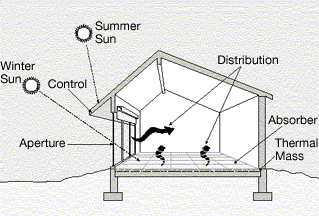

In passive solar building design, windows, walls, and floors are made to collect, store, reflect, and distribute solar energy in the form of heat in the winter and reject solar heat in the summer. This is called passive solar design because, unlike active solar heating systems, it does not involve the use of mechanical and electrical devices.

The key to designing a passive solar building is to best take advantage of the local climate performing an accurate site analysis. Elements to be considered include window placement and size, and glazing type, thermal insulation, thermal mass, and shading.

What are you designing for - how does the BAL rating fit in and what is it trying to achieve?

In addition to energy efficiency and overall structural soundness, construction requirements in bushfire-prone areas are determined based on the bushfire attack level that is likely. The BAL takes account of vegetation and slope of the building site, as well as vegetation in the surrounding landscape, also known as the landscape risk.

The BAL is a nationwide approach to determine the severity of a building’s potential exposure to ember attack, radiant heat and direct flame contact. It is measured using levels of radiant heat, expressed in kilowatts per square metre. The higher the number, the more severe the potential exposure. An exposure of 10kW/m2 can cause pain to humans after 3 seconds

There are 6 BAL classifications which form part of the Australian Standard for construction of buildings in bushfire-prone areas. The classifications indicate the materials and construction methods you’ll be required to use in your build.

The 6 classifications are:

- BAL low: Insufficient risk to warrant construction requirements – very low risk

- BAL 12.5: Ember attack – low risk

- BAL 19: Increasing levels of ember attack and burning debris along with exposure to a heat flux of up to 19kW/m²

- BAL 29: Increasing levels of ember attack and burning debris along with increasing exposure to a heat flux of up to 29kW/m²

- BAL 40: Increasing levels of ember attack and burning debris along with increasing heat flux of up to 40kW/m² and increased likelihood of exposure to flames

- BAL FZ: Ember attack and direct exposure to flames from the fire front in addition to a heat flux of greater than 40kW/m²

These levels are based on the following elements:

- Your location – this includes how many directions a bushfire may approach from as well as road access in and out of the property.

- The type of vegetation on your property – there is no such thing as fireproof vegetation as it can all burn in extreme fire conditions. The denser the vegetation the more intense the fire zone is. If there is a mixture of trees, shrubs, grasses and leaf litter this can have a kindling effect allowing the fire to build.

- How far your house is from vegetation – the closer the property is to vegetation the higher the fire risk. Research into Australian bushfires has indicated that around 85% of house destruction happens within 100 metres of bushland. The greater the area of bushland the greater the risk of direct exposure to flames.

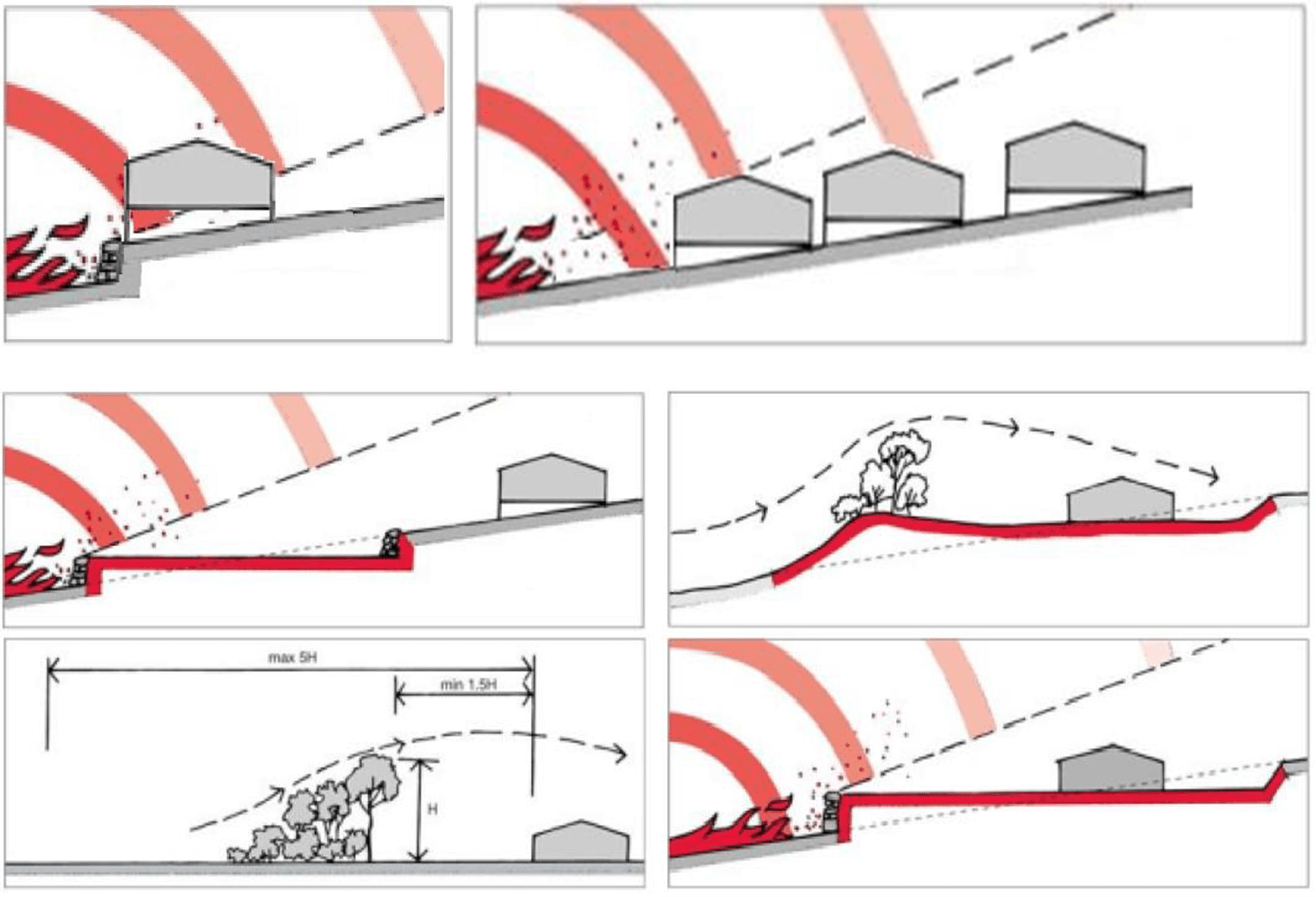

- The slope of your property – the topography affects the speed and spread of a fire. Fires burn faster uphill. When moving upslope, the fire dries out the vegetation ahead making it easier to burn. The steeper the slope, the quicker the fire. This is often a challenge, given preferences to site a home at the top of a slope to maximise views.

The planning and building permit processes in Victoria require that the BAL rating is determined as part of the approval process. Most of Victoria is declared Bushfire Prone which requires a building surveyor to determine the BAL for building permits.

Higher bushfire risk areas are also identified by the Bushfire Management Overlay in planning schemes requiring bushfire risk to be assessed for planning permit applications. This is normally done on a site-by-site basis or as part of an overall regional approach that is often implemented after a major bushfire event and supplied to landowners.

While many locations have lower BAL ratings (for example, 19 or 12.5), there is significant merit in deciding to construct to a higher BAL level - (for example BAL 29), to optimise the resilience that you put into a new structure. Whilst you cannot build to a lower BAL than has been assessed, you can always make your investment more resilient at your discretion.

This is an important consideration in cases where you may be rebuilding near to an existing structure that is not fire resistant. In these cases it may be prudent to adopt a design that has a higher fire resistance on the walls facing that hazard. This is particularly the case in townships or higher density residential areas where there is risk of house to house spread of fire.

What is the impact of the BAL on dwelling construction?

Embers, radiant heat, direct flame contact and increased wind speeds can all occur in a bushfire.

Generally, the more extensive the vegetation is in the surrounding landscape and the steeper the general terrain is, the greater likelihood there is of very intense fires with erratic behaviour and extensive ember attack developing. These are areas described as having high bushfire landscape risk.

While in some settings, houses will be exposed to direct flame contact, in almost any location in Victoria houses can be exposed to ember attack. Embers are a key source of house ignition and loss. Designing and building houses that are resistant to ember attack is a fundamental premise in being more resilient to bushfire impact. Embers can enter a building through gaps of 2mm.

At BAL 12.5, the primary objective is the use of non-flammable window screens and screening over other openings into a building to limit the ingress of embers. In bushfire prone areas in Victoria you cannot legally build to less than BAL 12.5.

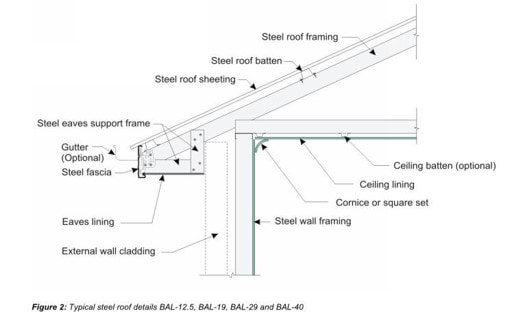

As the BAL rating increases, the use of non-flammable materials and methods of construction becomes more important. There is a need to fully seal roof spaces and underfloor areas to prevent embers from entering the internal parts of structures. The use of non-flammable insulation to seal wall cavities, non-flammable sealants and the like can also come into play.

Addressing the risk embers pose to a structure is fundamental as embers can fall on houses many kilometres from a fire front and can destroy houses even though the fire front did not directly impact the house.

Glass and windows become more expensive at the higher the BAL ratings, for example, BAL 40 and BAL FZ, so it is prudent to think carefully at the design stage about how and where glass is to be used and if window fire shutters are to be used. You should also consider if elements of the building design can be used to shield other parts of a structure from radiant heat. If you are able to site the structure in a location that has a lower BAL rating, then you may reduce your glass and window costs significantly.

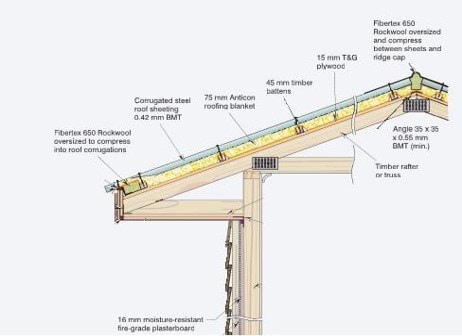

Generally, as BAL ratings increase, so do the requirements for and importance of constructing a dwelling using materials appropriate to the risk and implementing multiple layers of protection into the construction approach. For example, at higher BAL ratings, both the underside of the roof as well as above the ceiling should be covered and sealed with non-flammable insulating blanket or similar. This will minimise ember entry, as well as the consequence if some embers do get in. Non-flammable ceiling and wall insulation will also be required. At higher BAL ratings, non-flammable silicone sealants, filer strips and the like need to be used. This is an example of a layered approach to building resilience.

For this reason it’s important that the products and materials used and the build process are of sufficient high quality to ensure there are no gaps or holes left through which embers can get into the roof space or walls or underfloor.

The same careful approach is also required around the outside of the structure, particularly in respect to pipe locations and potential places where plastic pipe may be exposed to heat and melt creating an entry point for embers. The construction standards regulate these penetrations at higher BAL levels.

There are design and construction solutions to mitigate these risks and a wide variety of products and materials that can be used. Your builder or building designer can recommend and provide guidance as to which products are suitable.

Embers can enter through gaps as small at 2mm. That is why attention to detail is needed to ensure that your build is well put together, does not have gaps for embers to get through, and uses the right non-flammable materials so that things do not ignite.

As a general caution, the use of flammable expanding foams and other similar products to fill gaps or spaces around pipes is to be avoided in new building or in retrofitting unless they are protected from potential ignition.

The National Construction Code sets out a range of performance objectives for building in bushfire-prone areas that the building must meet. Your building surveyor will conduct periodic inspections during the build to ensure that these requirements are being met.

Victorian planning and building requirements also allow landowners to construct a private bushfire shelter or bunker. Because this may affect other parts of your rebuild plan, whether you wish to implement a bunker should be considered early in your conceptual planning phase.

The installation of a private bushfire shelter does not remove the need for the dwelling to comply with applicable planning and building requirements.

Fire sprinkler systems can be considered, but do not replace the need for the basic construction to be suitable for the bushfire exposure potential. This is particularly the case for a new build where eliminating combustible materials from the exterior of the building will generally be more effective and cheaper than a sprinkler system. There are a range of bushfire sprinkler systems that can be designed into the roof construction or retrofitted to an existing structure. Avoid any designs that can trap embers and other materials on the roof.

Manufacturers have developed a wide variety of building materials, products and systems of construction that are suited to building in bushfire prone areas and there are now many choices of products available that your design team or builder can recommend that best suit your needs.

Some common materials that are used for external cladding or primary construction include corrugated and other steel profiles, fibre cement sheet or moulded panels of the correct thickness, brick, cement, rammed earth and some timbers in lower BAL categories.

There are fire resistant sarking, roof and wall insulation products and sealants readily available.

While the cost of your construction will be influenced by many factors, at lower BAL ratings, there are no fundamental materials changes or limits on materials and no methods for construction over and above any normal building project.

At higher BAL ratings (40 and FZ) glazing costs do increase as do costs if shutters or other methods are implemented. Siting your structure to achieve a lower BAL exposure can have a big bearing on costs for windows and glazing and therefore your overall build cost.

Key changes to building elements as exposure to bushfire attack increases

BAL 12.5

Subfloor supports

No general construction requirements.

Floors

No general construction requirements.

External walls

Walls less than 400 mm from ground or decks to be of non-combustible material, 6mm fibre cement cladding or bushfire resistant timber.

External windows

Bushfire shutter or 4mm toughened glass.

Metal frame or bushfire resisting timber.

External doors

As for BAL–19 except that framing can be naturally fire-resistant timber.

Roofs

Non-combustible covering.

Openings fitted with non-combustible ember guards.

Roof to be fully sarked.

Verandas and Decks

Enclosed sub-floor space – no general requirement.

No special requirements for supports or framing.

Decking to be non-combustible or bushfire resistant near windows only.

BAL 19

Subfloor supports

No general construction requirements.

Floors

No general construction requirements.

External walls

Walls less than 400 mm from ground or decks to be of non-combustible material, 6mm fibre cement cladding or bushfire resistant timber.

External windows

Bushfire shutter or 5mm toughened glass.

Metal screening with frame of metal or bushfire resisting timber.

External doors

Bushfire shutter or screened with steel mesh or non-combustible or metal or bushfire resisting timber frame.

Roofs

Non-combustible covering.

Openings fitted with non-combustible ember guards.

Roof to be fully sarked.

Verandas and Decks

Enclosed sub-floor space – no general requirement.

No special requirements for supports or framing.

Decking to be non-combustible or bushfire resistant near windows only.

BAL 29

Subfloor supports

Enclosure by external wall, non-combustible supports where the subfloor is unenclosed, naturally fire-resistant timber stumps.

Floors

Concrete slab or enclosure by external wall or non-combustible flooring or naturally fire-resistant timber or wool insulation.

External walls

Non-combustible material (masonry, brick veneer, concrete) or steel framed walls sarked on the outside and clad with 6mm fibre cement sheeting.

External windows

Bushfire shutter or 5mm toughened glass.

Metal screening with frame of metal or bushfire resisting timber.

External doors

Bushfire shutter or screened with steel mesh or non-combustible or metal or bushfire resisting timber frame.

Roofs

Non-combustible covering.

Openings fitted with non-combustible ember guards.

Roof to be fully sarked.

Verandas and Decks

Enclosed sub-floor space or non-combustible or bushfire resistant timber supports.

Decking to be non-combustible or bushfire-resisting timber.

BAL 40

Subfloor supports

Enclosure by external wall refer below ‘External Walls’ section in table or non-combustible subfloor supports.

Floors

Concrete slab or enclosure by external wall or non-combustible material such as fibre cement sheet.

External walls

Non-combustible material (masonry, brick veneer, concrete) or steel framed walls sarked on the outside and clad with 9mm fibre cement sheeting.

External windows

Bushfire shutter or 5mm toughened glass.

External doors

Bushfire shutter or non-combustible or 35 mm solid timber, metal framed tight-fitting with weather strips at base.

Roofs

As for BAL 29 requirements.

No mounted evaporative coolers

Verandas and Decks

Enclosed sub-floor space or non-combustible supports.

Decking to have no gaps and be non-combustible.

BAL FZ

Subfloor supports

Enclosure by external wall or non-combustible with an FRL of 30/-/-

Floors

Concrete slab or enclosure by external wall or an FRL of 30/30/30

External walls

Non-combustible material (masonry, brick veneer, concrete) with minimum thickness of 90mm or FRL of -/30/30

External windows

Bushfire shutter or FRL of -/30/-

Steel or bronze screening.

External doors

Bushfire shutter or tight-fitting with weather strips at base FRL of -/30/-

Roofs

Roof with FRL of 30/30/30 or tested for bushfire resistance.

No mounted evaporative coolers

Verandas and Decks

Enclosed sub-floor space or non-combustible supports.

Decking to have no gaps and be non-combustible.

The structure itself

Approaches to construction

There are two main approaches to construction, traditional and prefabrication or modular.

Traditional

The traditional approach is for a structure to be erected on the development site from the ground up using timber or steel framing with brick or other suitable external cladding, or solid brick or concrete walls. Depending on the site conditions, concrete slabs, or sub floors on posts or other foundations are all possible.

Steel framed construction is an alternative to timber framed construction. There are specific standards for steel-framed construction in bushfire-prone areas with some advantages due to the non-flammability of steel framing and resistance to termite attack.

Assuming that there are no complex geotechnical issues affecting the site, at higher BAL levels glazing or window treatments will generally be the biggest cost variable over sites located in less risky locations.

Modular or prefabrication

The main alternative is prefabricated construction where the main parts of the structure are assembled off-site and then delivered to the site and joined together.

Travel time to a construction site may be a significant factor in overall build cost. In traditional approaches, builders will either need to stay on-site (if remote site), or have access to accommodation within reasonable distance to the construction site.

In modular construction, preparation of the prefabricated elements can proceed, generally in a factory setting, while site preparation and footings are prepared on-site.

There is potential time saving because both parts of the build process can occur simultaneously and preparation of modular units in a factory is not impacted by weather.

However, with modular or prefabricated construction, site access for potentially large premade components, trucks and crane access will be an important consideration that should be addressed in the conceptual and planning phase. Consider the route delivery trucks will take including road and bridge widths and load capacity, and vegetation or utilities that may impact delivery.

On steep sites or inaccessible sites, modular units can be helicoptered into position if road and crane access is not feasible. This may be a cost-effective approach depending on site considerations.

Builders and designers can provide advice on what approach to general construction makes the best overall sense and is the most practical, efficient and cost-effective for your site while achieving a bushfire resilient dwelling.

If you have an existing structure that is still habitable, or is being repaired, it is well worth reading the CFA guide to retrofitting existing houses to improve bushfire resilience.

Think non-combustible

Landscaping and other site treatments

While the house and any other main structures will require planning and building permits and must be built in accordance with the National Construction Code, general landscaping and other treatments that landholders undertake overtime generally do not need approval.

In areas exposed to bushfire risk, it is important to think about what is put into garden landscaping or near the house to avoid creating a potential risk to your house.

Think about what you put near the house or on your block

- Position gas bottles preferably away from the main structure in a manner where they can be suitably restrained. Ensure that gas bottles vent away from structures into clear air and do not hinder your main movement or escape routes.

- Think carefully in the future to ensure that any alterations or new features added to the house do not undermine the investment you have made. For example, the creation of new holes of gaps through walls that can let embers in.

- Use plants and landscaping that are sensible in fire risk areas – see the CFA landscaping guide

- Consider what materials you use for landscape features. If possible, use non-combustible materials such as stone, concrete or masonry or more resilient native timbers.

- Use non-flammable materials in any retaining walls.

- Consider use of non-flammable materials in waste treatment beds if you need to create them on steeper slopes.

- Avoid the use of flammable materials up close to the house. For example. treated pine steps can ignite doors.

- Avoid storing flammable things under houses.

- Think about how septic tank effluent can be used to sustain a green break around structures.

- Remember to only use metal pipes and fittings for all water systems above ground. A melted plastic pipe at the bottom of the hill can let all your firefighting water escape and will not comply with CFA requirements.

The planning permit process

In most cases a planning permit will be required. Engage early with your council to determine what approvals you need. Determine if you will seek professional assistance to prepare your application and supporting paperwork.

Key steps in finalising an application

Based on your concept plans, finalising an application for a planning permit generally includes:

Undertake a site analysis

- Take photographs of the site and surrounding area, including neighbouring properties.

- Prepare a site description and plan to illustrate the features of the site and surrounding area.

Prepare plans

- Prepare plans and initial site plan for your proposal, taking into consideration the opportunities and constraints identified by your site analysis.

- Prepare a design response statement, outlining how your preliminary design has responded to the site and surrounding area.

Talk to your neighbours

- Talking to your neighbours before finalising your plans is encouraged. If they are unhappy with an aspect of your proposal, you may be able to reach a compromise before lodging your application. This may help prevent concerns about the sharing of views, screening of windows and access to sites from the road.

Review and finalise your plans

- Consider feedback from staff at the Community Recovery Hub and your neighbours.

- Review your plans and incorporate any suggested changes that you consider reasonable.

- Finalise your plans and any written material, including your site description and design response.

- Refer to the checklist on the next page as a guide for application requirements.

Lodging your application

- After obtaining advice from the Community Recovery Hub and preparing the necessary documentation you will now be able to lodge your application with council. Remember to read over your application form carefully to ensure you have completed all relevant details and submit all required documentation with your application.

Application checklist

The following is a general list. Depending on the nature of the application additional information over and above the general requirements may be requested.

Please refer to specific factsheets and discuss with the Community Recovery Hub, as required.

Requirements for an application will vary but generally contain the following information:

- A covering letter explaining your proposal.

- Completed application form.

- Recent copy of title (no older than 60 days) from the Landata website

- Application fee (fee may be waived by council for rebuilding applications).

- Site survey (showing contours, site features, location of structures and vegetation on your land and close to the boundary on adjoining land, setbacks, land features between the site and the road, etc.).

- Neighbourhood and site description.

- A design response or explanation of the proposed use

- For residential properties in settlements, a response to the decision guidelines and description of how the development responds to the Clause 54 ‘Rescode’ standards.

- Site Development Plan, including layout of development and access from road, site contours, building setbacks, driveways and hard surface areas.

- For properties with landslip and erosion risk, a geotechnical assessment.

- Description of how the building siting and design responds to the BAL applicable to the property, including proposed bushfire mitigation measures.

- Land Capability Assessment for properties without connection to existing sewerage.

- Three copies of plans drawn to scale (1:100 or 1:200) and fully dimensioned.

- An A3 size set of plans (in addition to those mentioned above)

- Plans may need to show the site, floor layout and elevations, clearly showing building height above natural ground level and floor/roof levels that relate to the site contours

- Details of proposed external building materials and colours.

- Applications should show clear links between the site context plan, the design response and the development proposal.

Application requirements

Documents to be included with a planning application:

Covering letter

- Submit a covering letter with your application briefly describing your application and the details of any pre-application discussions with the Community Recovery Hub.

- This will ensure that officers assessing the application will be aware of any pre-application discussion.

A completed application form

- An application form must accompany every application.

- The application form must be complete before an application will be processed.

A response to key issues

Depending on where the site is, information on matters listed below may need to form part of the planning permit application.

Site survey

As part of your planning permit process to rebuild a house lost in the fires you may be required to re-establish your property boundary and undertake site specific surveys as part of your building and engineering work. This work could include a survey of easements, site levels and contours, the location of vegetation and other features.

Bushfires

The Bushfire Management Overlay (BMO) applies to many fire impacted properties. The planning control requires new development to consider bushfire protection measures including appropriate siting, water supply, access for emergency services and vegetation management.

A Bushfire Risk Assessment has been prepared for the Victorian Government by Terramatrix. Landowners are encouraged to provide their BAL level to an architect/designer or builder to begin the process of designing or creating a replacement dwelling, and to make an appointment with the Community Recovery Hub to discuss the initial design responses, and to seek clarification on any of the design standards.

To appropriately consider future bushfire risk, an application may require a Bushfire Management Plan that includes:

- The BAL in accordance with the preliminary assessment or an alternative assessment prepared by individual landowners

- location of a static water supply for firefighting and property protection purposes

- the provision of defendable space to the property boundary

- if proposed, the location of a private bushfire shelters (a Class 10c building within the meaning of the National Construction Code).

Landslip (East Gippsland Shire Council)

The risk of landslip has been identified as a significant hazard in Gippsland. Where the Erosion Management Overlay exists an application must include development plans drawn to scale and dimensioned, showing as appropriate:

- The proposed development, including a site plan and building elevations, access and any proposed cut and fill, retaining wall or effluent disposal system.

- Any existing development, including buildings, water tanks and dams on both the subject lot and adjacent land (as appropriate).

- Any existing development on the subject lot, including cut and fill, stormwater drainage, subsurface drainage, water supply pipelines, sewerage pipelines or effluent disposal installations and pipelines and any otherwise identified geotechnical hazard.

- Details and location of existing vegetation, including any vegetation to be removed.

Applications must also include a Geotechnical and Landslide Risk Assessment prepared by a suitably qualified geotechnical practitioner, specific to the proposed building design.

Landslip (Towong Shire)

The risk of landslip has been identified as a significant hazard across Towong Shire. Consequently, local policies apply to ‘steep land’ to manage risk. Development on properties with more than 20o slopes may require geotechnical assessments to appropriately consider the landslip issues on-site. An application must include development plans drawn to scale and dimensioned, showing as appropriate:

- The proposed development, including a site plan and building elevations, access and any proposed cut and fill, retaining wall or effluent disposal system.

- Any existing development, including buildings, water tanks and dams on both the subject lot and adjacent land (as appropriate).

- Any existing development on the subject lot, including cut and fill, stormwater drainage, subsurface drainage, water supply pipelines, sewerage pipelines or effluent disposal installations and pipelines and any otherwise identified geotechnical hazard.

- Details and location of existing vegetation, including any vegetation to be removed.

Applications must also include a Geotechnical and Landslide Risk Assessment prepared by a suitably qualified geotechnical practitioner, specific to the proposed building design.

Land capability and wastewater management

Land Capability Assessments will be prepared for impacted properties. This will assist landowners and architects to understand the design constraints associated with the sites. This will also inform individual property owners and their architects as to what additional property-specific investigations are needed to build a new house.

All applications will need to be accompanied by a Land Capability Assessment (LCA) prepared by a suitably qualified person that responds to the specific design proposed for a site, and which builds on the technical assessments provided by the Victorian Government.

Land subject to inundation

Some areas are in flood prone areas. This land is generally subject to a Flood Overlay (FO) or Land Subject to Inundation Overlay (LSIO). The key purpose of these controls is to:

- minimise the effects of overland flows and flooding on new buildings

- ensure new developments don’t adversely affect existing properties.

Overlays are based on the extent of flooding resulting from a 1 in 100-year event. This relates to a flood event of such intensity, based on historical rainfall data, which has a one per cent chance of occurring in any given year.

A feature survey may be required by a licenced land surveyor to identify the extent of the overlay on your property and elevations required to manage flood risk. Dwellings within these areas should be sited, designs and engineered to minimise risk.

Consultation with the Catchment Management Authority may be required.

Aboriginal cultural heritage

Many rural properties are within areas of cultural heritage sensitivity. While certain development may require a Cultural Heritage Management Plan, generally this is not needed to build a single house. For further information please discuss with the Community Recovery Hub.

Building permits

A building permit is required to carry out building work unless a specific exemption exists or the work is directed under a building notice, building order or emergency order. To rebuild a residential house impacted by a bushfire, you will need to obtain a building permit. Not all building projects require a building permit, and possible exemptions may include:

- some minor alterations or demolitions

- pergolas associated with houses, and

- some garden sheds with a floor area less than 10m2.

How to apply for a building permit

Before applying for a building permit, you need to appoint a registered building surveyor and apply for a building permit through them.

What documentation do I need to provide?

To apply for a permit, you need to:

- Submit at least three copies of drawings, specifications and allotment plans, along with the completed application form and other prescribed information.

- Pay the building permit levy yourself or through a person authorised to do so unless the fee has been waived as part of a coordinated bushfire event response. (Note in East Gippsland and Towong Shires fees have been waived).

Appointing a building surveyor

Building surveyors are professionals trained in understanding the building process. They are responsible for issuing building permits, carrying out mandatory inspections during the build process and having the authority to take enforcement action as necessary, to ensure compliance of building work with regulatory requirements and standards.

You will need to appoint a building surveyor for any project that requires a building permit.

Building surveyors are required to be registered and it is prudent to check their registration and whether there are any disciplinary actions against them before their appointment.

Only an owner or agent of the owner may appoint a private building surveyor. It is not the role of the local council or the Victorian Building Authority to appoint a private building surveyor. By law, the builder can't appoint the building surveyor to mitigate the risk of collusion between a builder and a building surveyor.

In your building permit, your building surveyor will specify the mandatory inspections that will be required throughout the course of the building work. They will also specify whether you need an occupancy permit or a certificate of a final inspection on completion of the building work.

When you come to the end of your building project, you will need an occupancy permit or a certificate of final inspection. If you need an occupancy permit, it is an offence under the Building Act 1993 to occupy any new building before you have received the permit. Your building surveyor will issue an occupancy permit when they are satisfied the building is suitable for occupation.

What a building surveyor does

A building surveyor is involved for the duration of the building work. They ensure the building work complies with regulatory requirements and they issue the building permits that allow work to commence. Building surveyors carry out inspections (or have a building inspector carry out inspections on their behalf) to ensure building work is being undertaken correctly. They also issue an occupancy permit or certificate of final inspection when the work is completed. In essence the role of the building surveyor is to ensure that your building is being built correctly.

A registered building surveyor is authorised to:

- assess building permit applications for compliance with the Building Act 1993, Building Regulations 2018 and National Construction Code

- issue building and occupancy permits, and certificates of final inspection

- conduct building inspections at the mandatory notification stages

- give directions to fix non-compliant building work

- serve building notices and orders.

Private bushfire shelters

A private bushfire shelter (commonly referred to as a bushfire bunker) is an option of last resort where people can take refuge during a bushfire while the fire front passes. It may be a prefabricated commercial product or a structure built on site.

The best way to ensure your safety during a bushfire is to leave your property early when it is recommended under the bushfire warning system and follow the CFA's advice. However, some people choose to construct a private bushfire shelter as part of their bushfire survival plan. Even if you are living in a Bushfire Prone Area, there is no legal requirement to build a private bushfire shelter – it is a matter of personal choice.

It is compulsory to obtain a building permit if you are building a private bushfire shelter on your property.

A building permit must be obtained for a private bushfire shelter before construction begins. Bushfire shelters have to comply with performance requirements set out in the Building Code of Australia, including safe accessing the shelter and maintaining acceptable conditions within the shelter when it is being occupied.

To obtain a building permit you will need to do one of the following:

- Purchase a shelter that has been accredited as meeting the performance requirements in the regulations by the Victorian Government’s Building Regulations Advisory Committee.

- Apply to the Building Appeals Board for a determination that your non-accredited bushfire shelter complies with the regulations.

- Obtain certification from a fire safety engineer who did not design the shelter to satisfy a building surveyor that your non-accredited bushfire shelter meets the requirements of the regulations.

It is important that you seek the advice of a relevant registered building practitioner, such as a fire safety engineer or a structural engineer, before you purchase or construct a private bushfire shelter, or before modifying an existing building to be used as a private bushfire shelter.

The Builder - registered building practitioners

If you are carrying out domestic building work (for example, rebuilding a house), you’ll need to use a registered building practitioner if the value of the work is more than $10,000. You can also check if a building practitioner or company is registered using the Victorian Building Authority Find a practitioner portal.

Owner-builders

You may wish to carry out the domestic building work as an owner-builder, where you will be responsible for carrying out the work on your own land. If the value of the domestic building work you will be doing is over $16,000, you will need to obtain a certificate of consent from the VBA to be an owner-builder.

To find out more, please visit Owner-builder eligibility or the Victorian Building Authorities owner-builder fact sheet.

What should you be looking for in a registered building practioner?

There are now a number of architects and building designers who have developed a range of built dwellings that are designed for all BAL types.

Many builders now have experience in construction methods and outcomes required in bushfire resilient construction.

As the client for whom the house is being built, the most important considerations are that the builder you choose to use is appropriately registered to carry out the required work, has the necessary insurances and that that they have no disciplinary actions against them. It is prudent to check reviews of previous work they have completed.

Beyond materials used and the overall design, the primary outcome sought by the construction standards to mitigate bushfire risk is that the structure is well sealed against the ingress of embers or flame into the interior parts of the building. You should seek out builders who demonstrate good attention to detail.

You need an efficient and well-organised builder, particularly for more remote sites where access to materials may be limited or require significant time to collect from materials suppliers.

You will engage your builder using a building contract and it is recommended that you visit the Department of Transport and Planning website for information in relation to:

- building

- builders

- quotations

- contracts, and

- consumer protection.

You are making a significant investment and should protect your own interests.

Key links

Australian Institute of Architects

Established in 1930, the Australian Institute of Architects is the peak body for the architecture profession in Australia. They represent over 11,500 members globally and are dedicated to improving our built environment and the communities we call home by promoting quality, responsible, sustainable design. The built environment shapes the places where we live, work and meet. It affects how spaces and places function and has the potential to stimulate the economy and enhance the environment.

The resources section of their website gives a broad range of advice and guidance on good building design, sustainable design principles and examples of designs for high fire risk areas.

Australian Institute of Building Surveyors

The peak body for Registered Building Surveyors with focus on continuous professional development and information sharing.

Bushfire Building Council of Australia

The Bushfire Building Council of Australia Ltd is an independent, not-for-profit organisation.

They are a network of:

- bushfire scientists

- fire safety engineers

- bushfire architects

- community risk management specialists

- bushfire behaviour experts

- materials chemists, and

- policy and regulatory experts.

They are committed to radically improving the resilience of properties and whole communities through innovative, evidence-based approaches to community safety and are developing assessment tools to help landowners and communities assess and manage bushfire risk.

Consumer Affairs Victoria provides extensive advice for consumers of products and services.

Advice is provided in relation to:

- building contracts

- selecting a building team

- obtaining quotes, and

- many other aspects of undertaking a building project.

Information on planning for bushfires and how to create your own fire plan.

Guidance on bushfire planning requirements, templates for developing bushfire plans and practical measures to retrofitting existing houses to improve resilience to bushfire impact.

Australia's national science research agency, solving the greatest challenges using innovative science and technology.

They provide:

- Research on bushfires and impacts on structures.

- Useful publications on improving resilience to bushfire, including Joan Webster OAM’s Essential Bushfire Safety Tips.

They are currently developing enhanced guidelines for building resilience in bushfire prone areas in conjunction with the Queensland Government.

Department of Transport and Planning

The Department of transport and planning are the custodians of the Victorian Planning and Building Systems. They provide:

- Guidance on planning and building approvals and how the planning and building systems work, including templates and examples.

- Online search capability to check planning scheme zones and any other overlays or controls affecting land.

Design Matters is the peak body for the building design profession.

Their website offers search capabilities to find building designers, planners, and other skills.

Energy Safe Victoria is the state regulator of all electrical trades and activities.

Their website features an online register of all licensed electricians.

Engineers Australia is the largest and most diverse body of engineers in Australia representing around 100,000 professionals at every level, across all fields of practice.

Committed to advancing engineering and the professional development of its members.

Environment Protection Authority (EPA)

The Environment Protection Authority sets regulations and standards for activities that may impact the environment or human health.

This includes requirements for rainwater tanks for drinking water, and requirements for the installation and use of on-site waste systems including septic tanks.

The Fire Protection Association is the peak body for fire protection professionals.

Their website provides links to professionals able to provide bushfire risk assessments, bushfire attack level assessments as well as design of fire suppression systems.

The Housing Industry Association is a member-based association promoting excellence in building and continuous skills development.

Their website has a range of informative material, including industry standard contracts and other like information.

The Masters Builders Association is a member-based association promoting excellence in building and continuous skills development.

National Association of Steel-Framed Housing (Nash)

NASH is an industry association centred on light steel structural framing systems for residential & commercial construction.

They support the development of standards for steel framed housing construction in high fire risk areas and have a variety of information products and publications on the benefits of steel framing in the context of bushfire.

Planning Institute of Australia

The Planning Institute of Australia (PIA) is the national body representing planning and the planning profession.

Through education, communication and professional development, PIA is the pivotal organisation serving and guiding thousands of planning professionals in their role of creating better communities.

Their website has a range of topical information on bushfire planning and development issues and a members search tool.

PrefabAUS is the peak body for Australia’s off-site construction industry and acts as the hub for building prefabrication technology and design.

The Victorian Building Authority are the regulators of building and plumbing in Victoria.

They provide advice on registration currency as well as disciplinary matters.

Their website has a range of information on building in Victoria, and rebuilding after a bushfire including retrofitting existing structures.