- Date:

- 31 Dec 2020

ISBN 978-0-7594-0859-3

List of figures

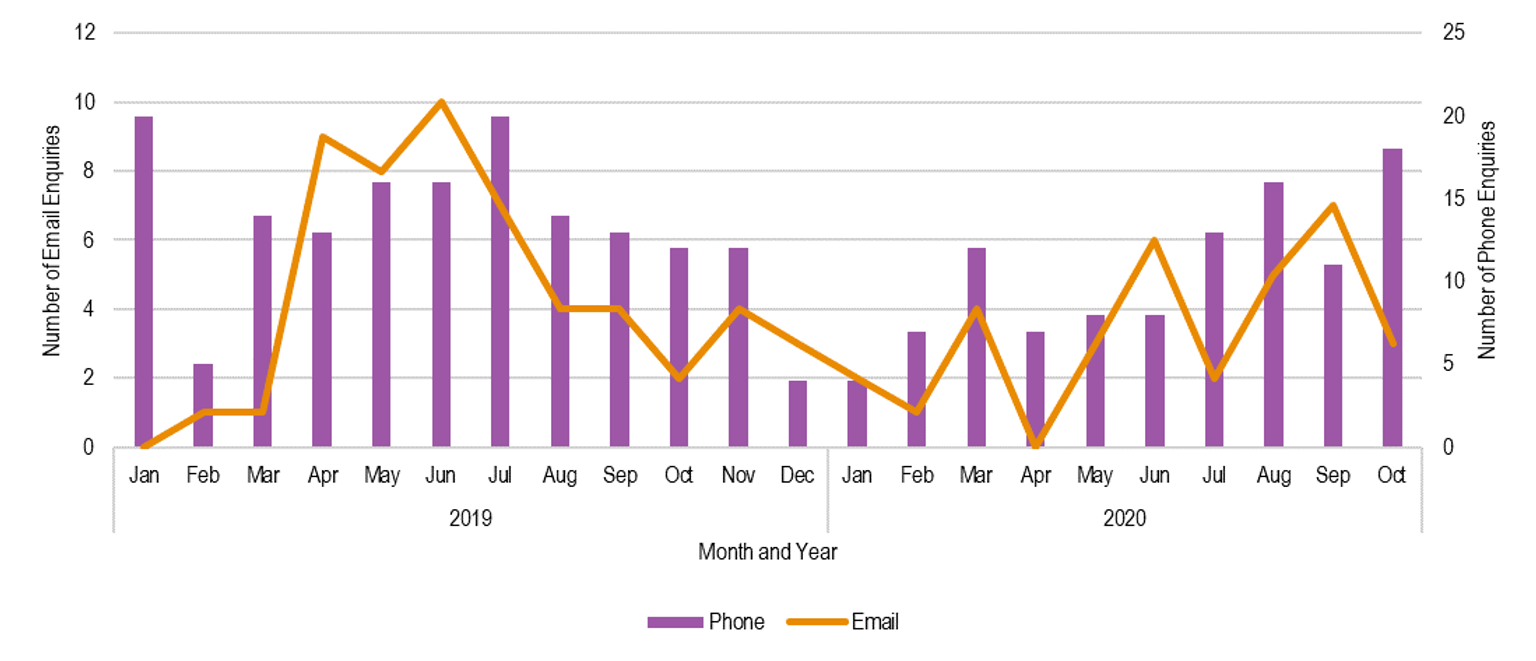

Figure 3.1: Enquiries through the information sharing reforms dedicated enquiry line (phone) and inbox (email).

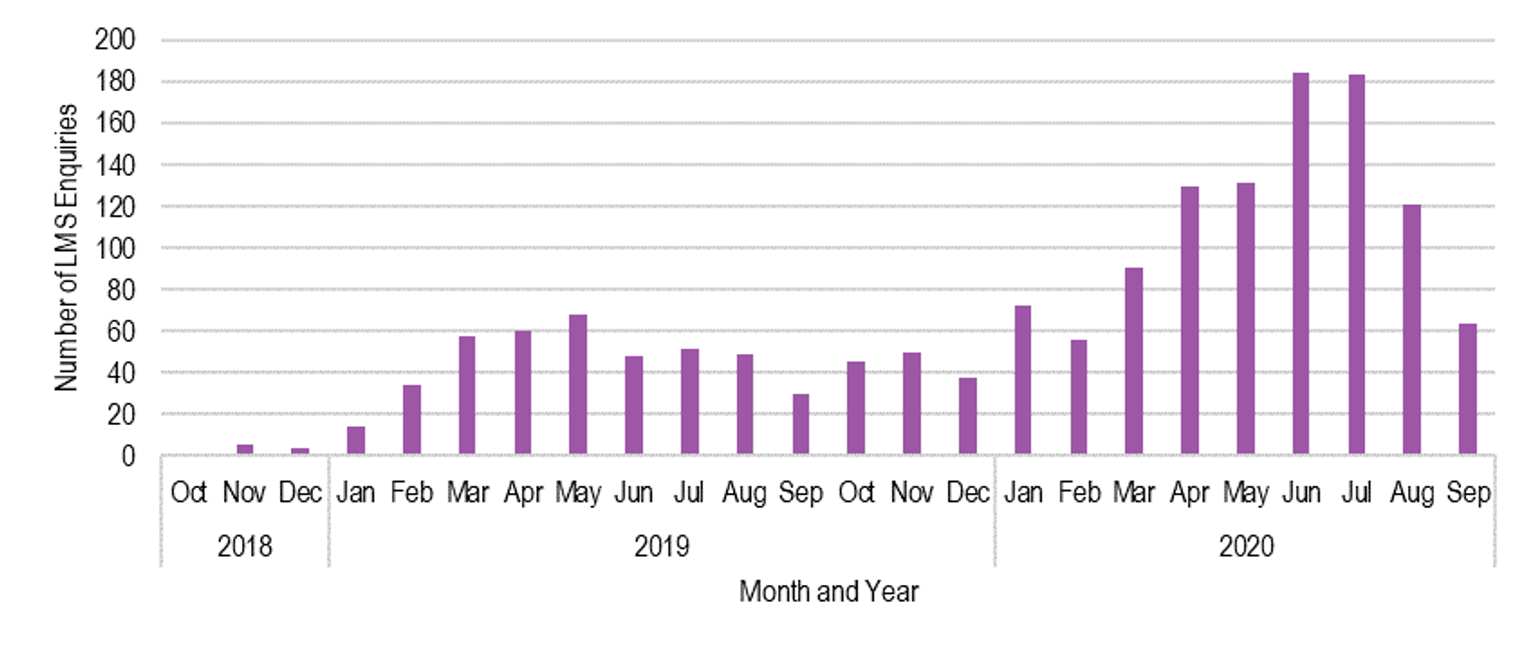

Figure 3.2: Email enquiries in relation to online training through the LMS.

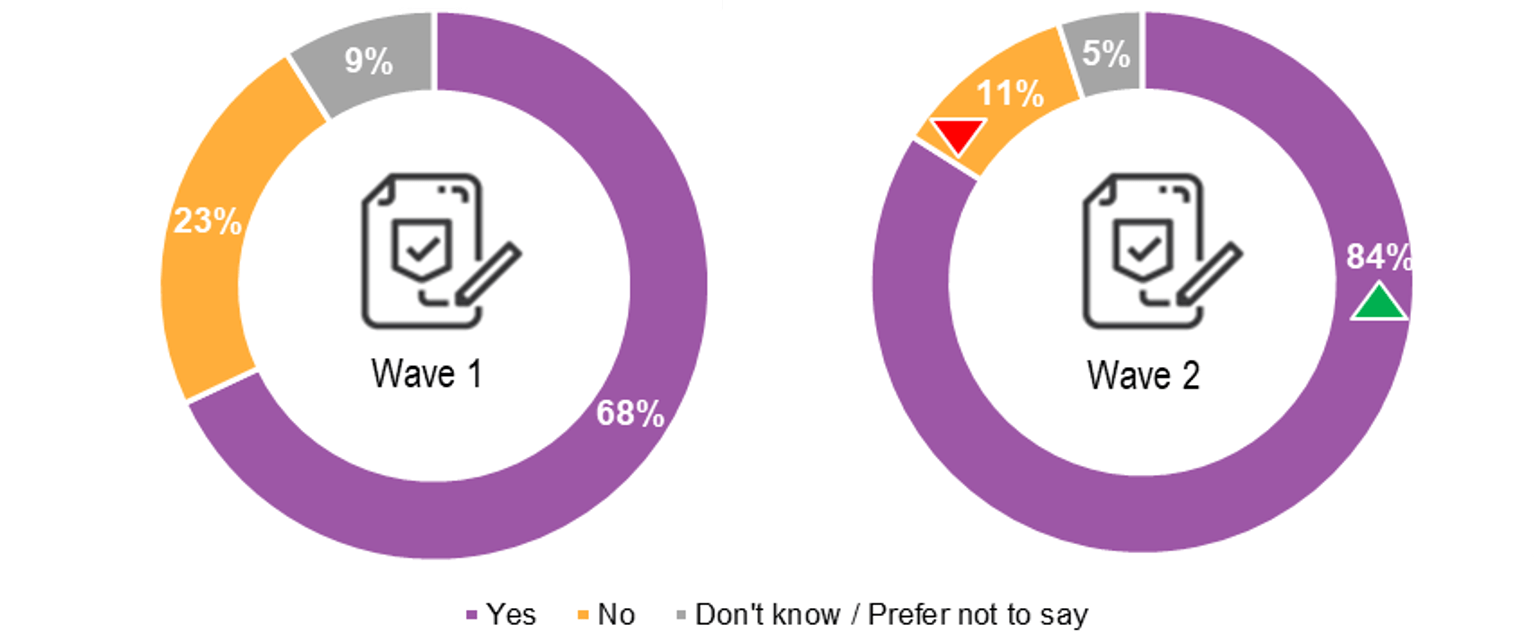

Figure 3.3: Proportion of workforces indicating their organisation had policies covering child information sharing prior to and following commencement of the CIS Scheme.

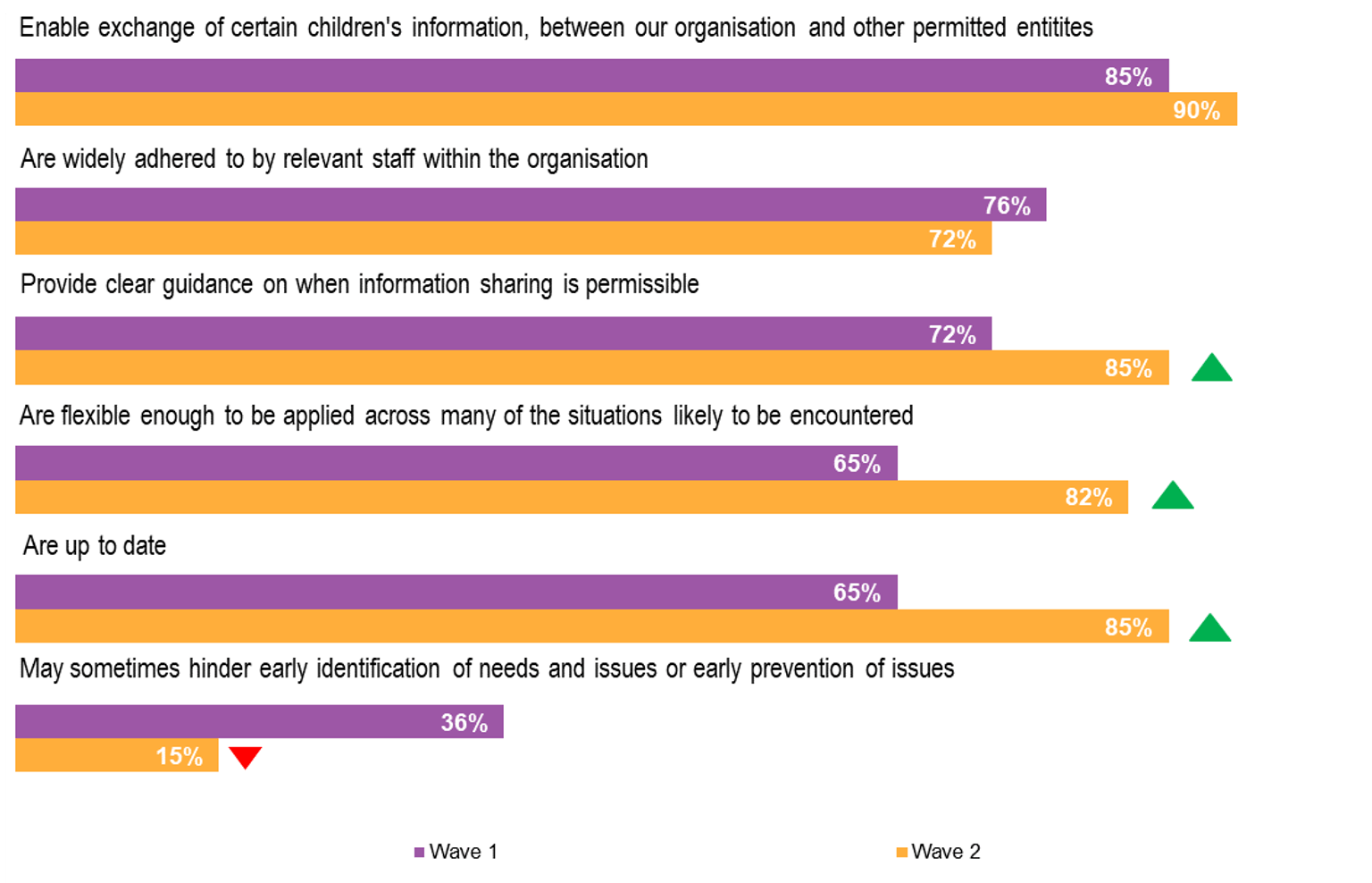

Figure 3.4: Workforce perceptions of information sharing policies.

Figure 3.5: Workforce attitudes towards information sharing.

Figure 3.6: Proportion of survey respondents by changes to organisational record keeping before and after implementation of the CIS Scheme.

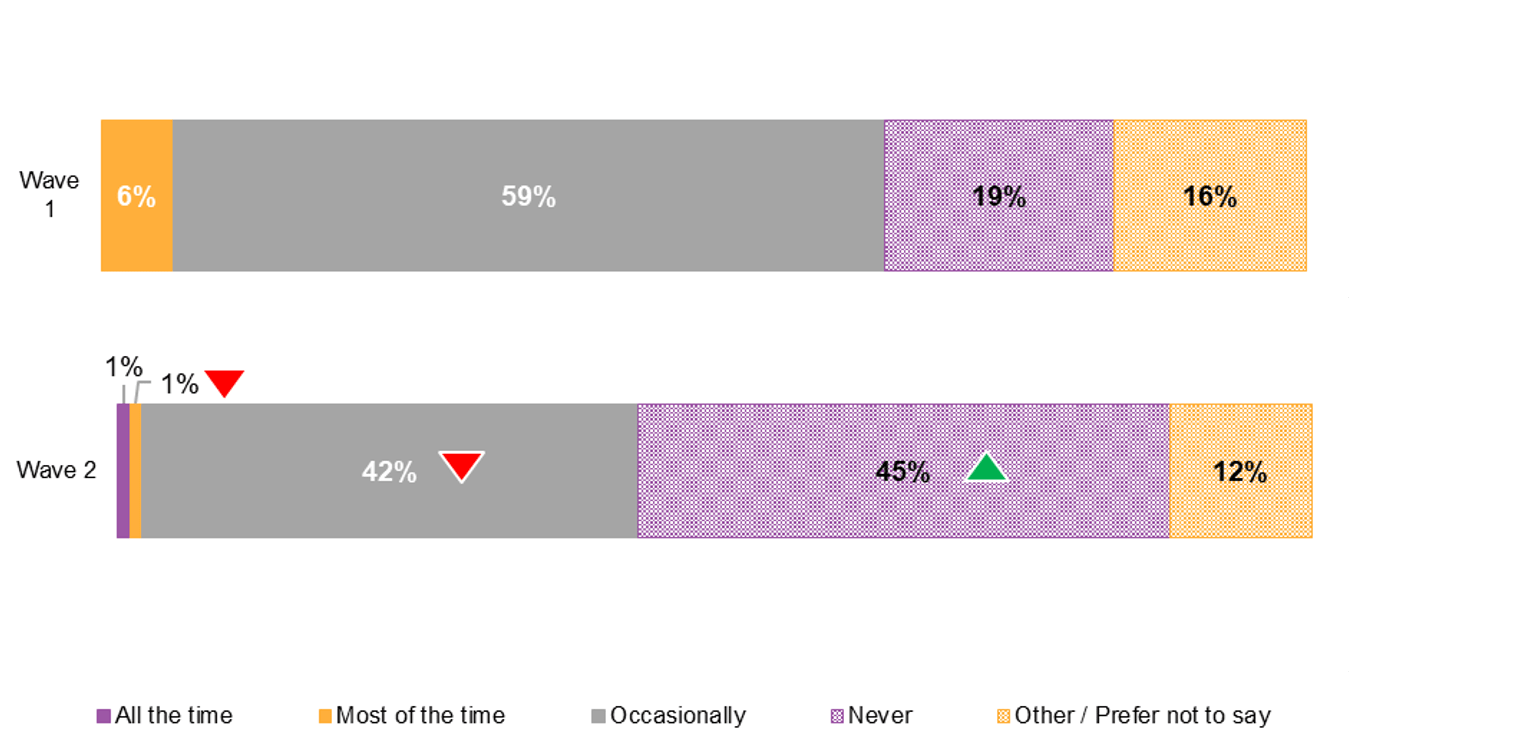

Figure 5.1: Frequency of refusals of incoming requests to share information among prescribed workforces.

Figure 5.2: Reasons for refusals of incoming requests to share information among prescribed workforces.

Figure 5.3: Frequency of refusals of outgoing requests for information among prescribed workforces.

Figure 5.4: Reasons for refusals of outgoing requests for information among prescribed workforces.

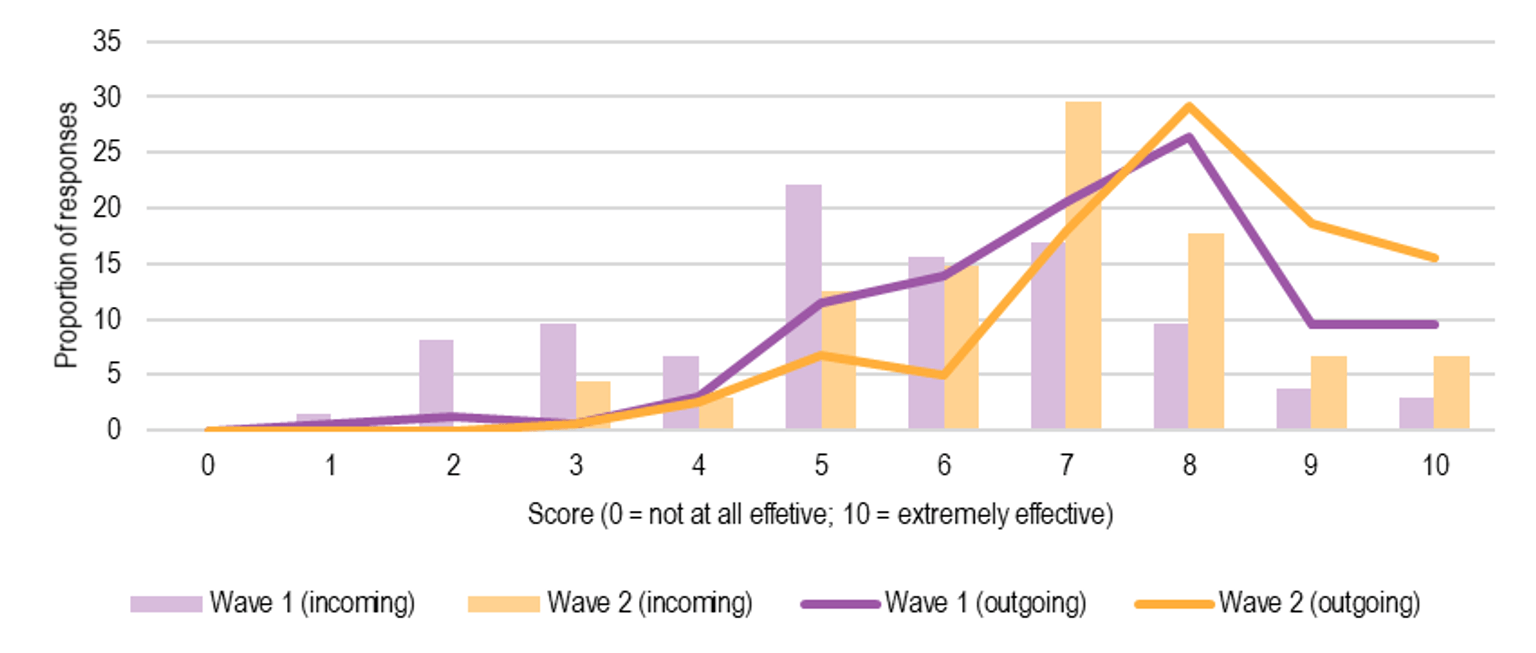

Figure 5.5: Workforces’ perceived effectiveness of information sharing to support child wellbeing, before and after CIS Scheme.

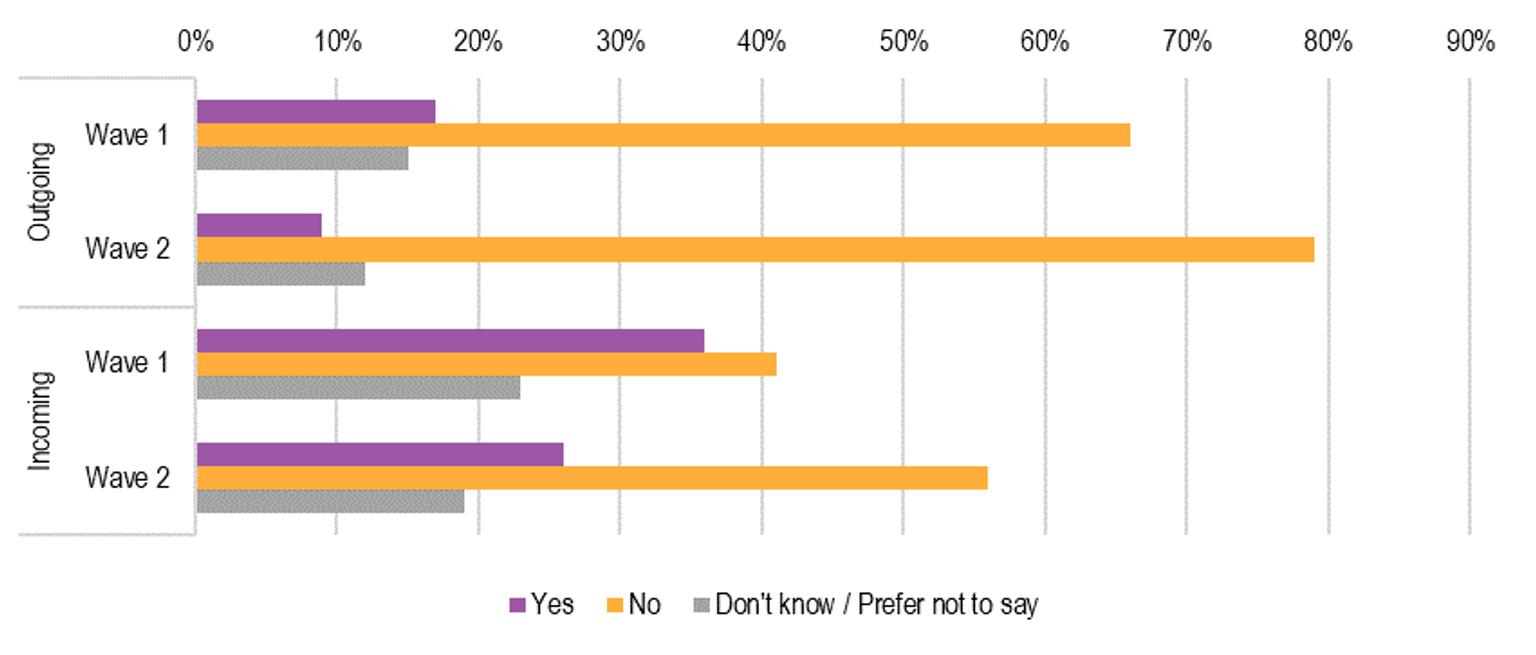

Figure 5.6: Enhanced ability to promote child wellbeing.

List of tables

Table 2.1: CIS Scheme Two-Year Review data collection activities.

Table 3.1: Proportion of enquiry line contacts by area of enquiry.

Table C.1: Profile of respondents who answered 2019 and 2020 Phase One prescribed workforces surveys.

Table C.2: Roles of respondents who answered in both workforces survey 2019 and 2020.

List of boxes

Box 3.1: Key findings – CIS Scheme implementation.

Box 3.2: Case study in implementation – Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

Box 4.1: Key findings – implementation enablers and barriers.

Box 5.1: Key findings – achievement of outcomes.

Box 5.2: Case study – proactive information sharing.

Box 5.3: Case study – filling crucial information gaps.

Box 6.1: Key findings – unanticipated adverse impacts of the CIS Scheme.

Box 7.1: Key findings – prescription of phase one entities under the CIS Scheme.

Box 8.1: Key findings – impact of the CIS Scheme on diverse and disadvantaged communities.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution to this review of key stakeholders who participated in data collection activities to determine the effectiveness of implementation of the Child Information Sharing Scheme. Insights and experiences with information sharing across a diversity of sectors were generously provided by workforces and senior representatives of prescribed organisations and services and related sector peak/lead bodies.

We also thank key informants representing partner government departments and agencies for information about policy, support and practice related to information sharing reforms from a state-wide perspective, and the Department of Education and Training, as the lead department for the child information sharing reforms, for the support provided to this review.

We especially acknowledge the cooperation of service providers during the latter phase of this review when child and family related services were experiencing the additional demands that accompanied the coronavirus pandemic and the workplace challenges of continuing to safely support their clients and communities.

Abbreviations and acronyms

| ACCOs | Aboriginal community controlled organisations |

| AHPRA | Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency |

| AOD | Alcohol and other drugs |

| CALD | Culturally and linguistically diverse |

| CCYP | Commission for Children and Young People |

| CIS Scheme | Child Information Sharing Scheme |

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| DHHS | Department of Health and Human Services |

| DJCS | Department of Justice and Community Safety |

| FSV | Family Safety Victoria |

| FVIS Scheme | Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme |

| ISEs | Information sharing entities |

| ISMARAM | Information Sharing and Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework |

| IST | DHHS Information Sharing Team |

| LGBTIQ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and/or queer |

| LMS | Learning Management System |

| MARAM | Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework |

| MCH | Maternal and Child Health services |

| TPAG | Training and Practice Advisory Group |

| VicPol | Victoria Police |

Key findings

Implementation

- Initial state-wide roll out of an intensive training program for Phase One prescribed workforces related to the information sharing reforms was attended by approximately 2,000 participants and served to create an awareness of the reforms within three months of their commencement.

- Additional training was provided by relevant government departments tailored to their respective workforces.

- Follow up support for Phase One implementation is ongoing and includes a range of learning resources and an enquiry line. There have been more than 6,000 registrations for online training.

- Family Safety Victoria sector grants to relevant peak/lead bodies have been important to extending the reach and understanding of the information sharing reforms among diverse sectors and workforces with varying experience of child-focus practice.

- Stakeholder feedback suggests there is continuing need to upskill prescribed workforces in the legislative provisions and requirements of the Child Information Sharing (CIS) Scheme to support effective implementation across the information sharing entities.

- Further work is required to support a consistent and informed level of understanding of the threshold for application of the CIS Scheme.

- There is evidence of improved workforce attitudes to child information sharing since commencement of the CIS Scheme and preparedness to share information.

- While organisational policies are in place to support workforces in implementing the CIS Scheme, there may be a low level of compliance with the record keeping obligations in the Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018 and explained in the Ministerial Guidelines.

Enablers and barriers to implementation

- Stakeholders have identified enablers and barriers to implementation of the CIS Scheme that relate to issues such as the anxiety of workers around privacy and confidentiality concerns, translation of policy into practice and understanding of child-focus practice.

- Data on information sharing requests is thin and will need to improve for effective and ongoing monitoring of the child information reforms.

- A number of strategies have been adopted by prescribed organisations and services to target culture change in support of effective implementation of the CIS Scheme. There is opportunity to better disseminate these innovative approaches to the potential advantage of Phase One and Phase Two prescribed workforces.

- While there is a high level of understanding about the purpose of the CIS Scheme further work is required to embed practice.

Achievement of intended outcomes

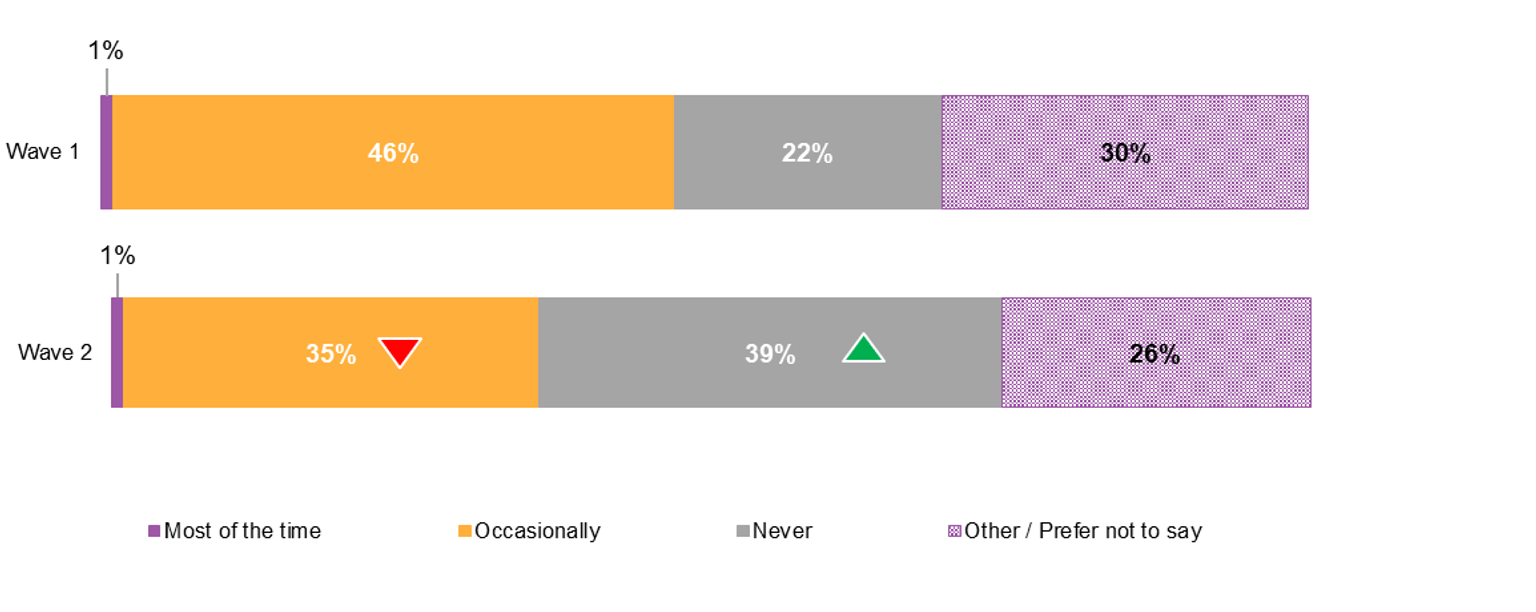

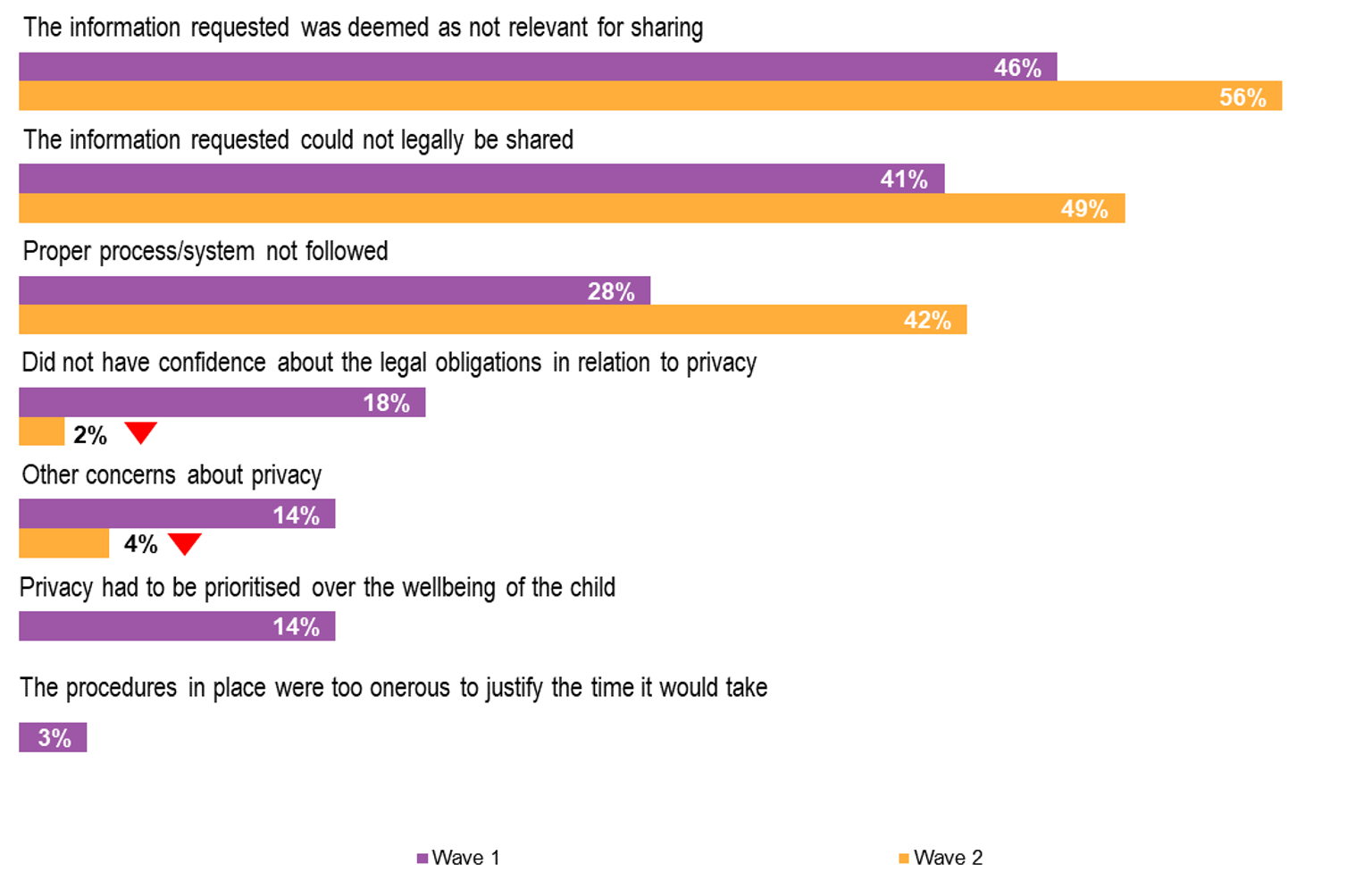

- Among prescribed workforces surveyed, there was a perception that legal restrictions and organisational policies that inhibited information sharing had decreased since commencement of the CIS Scheme, and that they were less likely to refuse a request for information after the introduction of the CIS Scheme. Privacy was also less likely to be cited as a reason to be used for refusing requests for information but was still likely to be a factor when survey respondents’ requests for information were refused.

- Information sharing activity appears to have remained mostly the same since commencement of the CIS Scheme based on the results of the surveys of prescribed workforces, with some evidence pointing to a slight decline in the level of activity. Other evidence suggests that during the coronavirus pandemic there may be specific forms of information sharing activity that have increased while others have decreased.

- There is some evidence for a cultural shift towards early identification of supports for children, with some prescribed workforces appearing to have lower thresholds for seeking information.

- Prescribed workforces also appear to be considering a wider range of information sources when doing case planning for children.

- There is increased evidence of collaboration and coordination between sectors at various levels, including between peak bodies, individual services, and individual workers.

- Continued support and education is required to build on early signs of positive outcomes to ensure that these reforms are firmly embedded among information sharing entities.

Unintended adverse impacts

- The formalisation of information sharing practices among some information sharing entities has caused local relationships to decline as informal information sharing between local agencies has decreased. However, it is noted that previous options for information sharing may not have been appropriate and an objective of the CIS Scheme was to provide confidence around the legality of child information sharing.

- In some cases, the CIS Scheme has complicated information sharing procedures for information sharing entities that previously shared information through other mechanisms. Information sharing entities are preoccupied with thinking about whether the CIS Scheme can be used and neglected the fact that they previously shared information through other avenues.

Prescription of information sharing entities

- Alignment of implementation of the CIS Scheme with the Family Violence Information Sharing (FVIS) Scheme and Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework was seen by Phase One prescribed workforces as consistent with the integrated way in which these reforms were being operationalised in practice.

- Interface of the FVIS and CIS Schemes has highlighted practices that can be strengthened to ensure the successful implementation of the CIS Scheme that include reinforcing the importance of routinely gathering accurate information, formalising standards for information collection and developing processes for documenting information sharing occasions and outcomes.

- Improved sharing of information between secondary/tertiary and universal services was considered to be more likely to deliver the early intervention benefits intended for the CIS Scheme, and the opportunity to promote child wellbeing outside of family violence contexts.

- For some Phase One prescribed organisations and services, expanding the CIS Scheme under planned Phase Two will enable a whole of organisation approach to the CIS Scheme and collaboration with other internal services to be prescribed under Phase Two.

- Choice of information sharing entities for Phase One has been appropriate when reflecting on the scale of implementation and the training required. There is a continuing need to build child information sharing capacity among Phase One information sharing entities.

- The selection of Phase One information sharing entities has illustrated the breadth of service providers in contact with children directly or indirectly through a family context and supports provided to parents/carers, and the opportunities to build a wider network of services able to participate in promoting child wellbeing and safety.

Impacts on diverse and disadvantaged communities

- The continuing need to improve engagement of diverse population groups with support services will affect the extent of the impact of the CIS Scheme in this area.

- More robust data collection related to application of the CIS Scheme will be required to monitor and assess use and impact of the CIS Scheme with diverse communities.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

- Aboriginal communities continue to be hesitant about information sharing being unsafe as:

- the CIS Scheme is not perceived to have been developed by Aboriginal people

- distrust and fear of the removal of children persists

- There is support for development of Aboriginal community understanding about the CIS Scheme, and the development of culturally appropriate training and resource materials for prescribed workforces.

- Consistent with the broader investigation of approaches to improve access to, and participation in services by diverse population groups, an improved understanding of issues that could potentially jeopardise sharing of child information will be important to avoid undermining engagement with services.

Executive summary

Executive summary of the Child Information Sharing Scheme Two-Year Review report.

Background

Child Information Sharing Scheme

The Child Information Sharing Scheme (the CIS Scheme) expands the circumstances in which professionals and organisations can share information to promote the wellbeing and safety of children. The CIS Scheme was proclaimed in September 2018 under the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 to enable prescribed organisations and services (information sharing entities) to share confidential information in a timely and effective manner. The first phase of information sharing entities are specified by the Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018 and were proclaimed on 27 September 2018. Phase One is comprised of approximately 28,000 workers representing around 700 entities primarily within the secondary and tertiary sectors. Phase One information sharing entities generally had high level permissions to share information about children and families and, with exceptions such as services working predominantly with adults, the impact of extending these permissions under the CIS Scheme was expected to be minimal.

The CIS Scheme forms part of the child information sharing reforms, together with a web-based Child Link Register currently under development to streamline access to information about participation of children in government-funded programs. It is expected that these reforms will:

- improve early needs and risks identification and support for children and their families

- change a risk averse culture in relation to information sharing

- increase collaboration and integration between child and family services

- support children’s and their families’ participation in services to which they are entitled.

Ministerial Guidelines were developed to support implementation of the CIS Scheme providing more detailed information including about the legislative principles for the CIS Scheme and the threshold for determining use of the CIS Scheme.

The CIS Scheme operates alongside family violence prevention reforms introduced similarly to support effective sharing of information between authorised organisations and services. The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (the FVIS Scheme) enables information sharing to facilitate assessment and management of family violence risk to children and adults, and the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework guides information sharing under both information sharing schemes where family violence is present. The majority of the Phase One information sharing entities are prescribed under both information sharing schemes and the MARAM Framework. Depending on the circumstances and authorisations, Phase One information sharing entities may use either of the schemes on their own or apply both schemes where family violence is present and there are wellbeing and other safety concerns for children.

Governance arrangements for the CIS Scheme reflects a multi-agency approach consistent with the legislative intent and responsibility for the information sharing reforms. The Department of Education and Training leads the child information sharing reforms in close partnership with Family Safety Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Justice and Community Services and Victoria Police. In anticipation of a significantly expanded group of professionals and services with the commencement of Phase Two of the CIS Scheme in the first half of 2021, new governance arrangements provide a strengthened focus on CIS Scheme implementation.

Purpose of this review

An independent review of the operation of the CIS Scheme within two and five years of commencement is required under section 41ZN of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005. This review represents the two-year review of the CIS Scheme covering the period September 2018 to September 2020. The two-year review was required to:

- Determine to what extent the CIS Scheme has been implemented effectively.

- Identify key enablers and barriers to implementation.

- Determine to what extent the CIS Scheme is achieving its intended outcomes.

- Consider and identify any adverse impacts of the CIS Scheme.

- Assess the success of the prescription of Information Sharing Entities.

- Assess impacts on diverse and disadvantaged communities.

- Include recommendations (as necessary) on any matters addressed in the review.

The review report is structured around these key areas of inquiry.

An independent review of the FVIS Scheme overlapped with this review both in terms of timeframe and information sharing entities. The recommendations of the FVIS Scheme two-year review, tabled in Parliament in August 2020, address shared issues. The recommendations have subsequently been supported in full or in-principle by the Victorian Government.

Review approach

The review commissioned by the Department of Education and Training was conducted by ACIL Allen Consulting in partnership with Wallis Market and Social Research Centre (Wallis). A program logic developed for the CIS Scheme underpinned the guiding evaluation framework and the collection of qualitative and quantitative information from a variety of new and existing sources. Data collection focused on stakeholder engagement and occurred predominantly at two points in time commencing in July 2019 with follow up in June 2020.

Information gathering focused on establishing attitudes and practices of workforces of prescribed organisations and services (prescribed workforces) to information sharing, the support provided by peak/lead bodies to their respective sectors for effective implementation of information sharing reforms and the extent of change to organisational record keeping processes and systems to facilitate implementation of the CIS Scheme. Data collection methods included surveys, interviews, virtual workshops, document review and case studies.

Implementation of the Child information Sharing Scheme

Workforce training

Initial intensive, face-to-face training for workforces of the Phase One information sharing entities was conducted during October to December 2018. The training approach was informed by a needs analysis and the deliberations of a Child Information Sharing Working Group with membership from relevant areas of government, and consultations with a Training and Practice Advisory Group with expertise across relevant workforces. The training adopted an integrated approach covering content for both information sharing schemes and an introduction to the MARAM Framework. Training was attended by approximately 2,000 participants, 35% of whom attended regional sessions.

Lead agencies driving the reforms considered that the training had served to create an awareness of the CIS Scheme and related information sharing reforms and to inform refinement of the strategic approach to building capacity among the Phase One information sharing entities. Subsequent training developed by partner government departments was tailored to their workforces, and peak/lead bodies were supported to develop sector specific supporting materials and resources. Whole-of-Victorian Government implementation supports for the CIS Scheme are predominantly provided through a variety of platforms managed by the Department of Education and Training. These include eLearning modules, with over 6,000 enrolments to date, Ministerial Guidelines that are legally binding for information sharing entities explaining operation of the CIS Scheme and a dedicated Enquiry Line for queries related to the information sharing reforms.

Utilisation of the Enquiry Line over the 18-month period to June 2020 suggests a growing understanding of the reforms although decreased contacts may also reflect awareness about, and access to a wider range of guidance and learning resources. Approximately 60% of all queries were related to the CIS Scheme, suggesting that the Enquiry Line will be an ongoing valuable source of support for information sharing entities.

In addition, the Enquiry Line could be harnessed to provide a better understanding in ‘real time’ of the nature and proportion of enquiries related to the CIS Scheme and the category of information sharing entity seeking clarification. This information could inform monitoring of the implementation of the CIS Scheme and any gaps in understanding at workforce and service level that might warrant targeted or different support.

| Recommendation ES 1 Enquiry Line Data Collection |

|---|

| That operation of the Enquiry Line be funded to accommodate the expansion of information sharing entities under the information sharing reforms, and to facilitate the collection of ‘real time’ data to inform effective implementation of the child information sharing reforms. |

Sector Grants Program

The Family Safety Victoria Sector Grants Program introduced in 2017-18 has provided sector implementation support funding to key representative and state-wide bodies for implementation of the information sharing and MARAM reforms. The Sector Grants Program focuses on implementation of the information sharing reforms in a family violence context. Whilst the activities supported by the Grants Program have benefited operation of the CIS Scheme, peak/lead bodies have not had the resources to bring a similar focus to the CIS Scheme and its wider application. Feedback from peak/lead bodies indicates that there is continuing work to successfully embed the CIS Scheme in prescribed organisations and services.

The Sector Grants Program has demonstrated the value of supporting targeted initiatives for key workforces in promoting effective implementation of reforms. There is opportunity to better leverage the support of peak/lead bodies in complimenting other efforts to promote early intervention and prevention through improved child information sharing. This support would be especially timely in also facilitating collaboration between peak/lead bodies representing sector workforces prescribed in Phase One of the CIS Scheme and proposed for Phase Two.

| Recommendation ES 2 Sector Support |

|---|

| That support be provided to sector peak/lead bodies, similar to the Family Safety Victoria sector grants, to strengthen the response to sector-specific needs of information sharing entities in understanding and applying the CIS Scheme in a range of circumstances and to promote cross sector collaboration and consistency. |

Perspectives of prescribed workforces

Feedback in 2020 through open-ended questions in the follow up 2020 workforces survey and workshops with prescribed organisations and services, suggests that CIS Scheme training and supporting resources continues to be a priority issue for prescribed organisations and services.

An area of continuing challenge for a number of information sharing entities has been interpretation of the concept of ‘wellbeing’ associated with use of the CIS Scheme which suggests a lack of confidence in the capacity for professional judgement in determining application of the CIS Scheme and highlights the varied familiarity of information sharing entities with child-focused practice frameworks. While universal services to be prescribed under Phase Two of the CIS Scheme are familiar with wellbeing frameworks, this is not the case for many Phase One prescribed workforces with a risk focus and adult user group. In addressing this concern, It was considered necessary to balance the original intent of the legislation regarding the importance of the breadth of circumstances relevant to wellbeing, while providing additional guidance to workforces on how they should assess and understand wellbeing for the purposes of the CIS Scheme.

| Recommendation ES 3 Assessing Threshold for ‘Wellbeing’ |

|---|

| That further guidance be provided for prescribed workforces regarding expectations associated with ‘promoting child wellbeing’ under the CIS Scheme. That this further guidance be informed by an audit of state-wide and sector specific resources with the aim of identifying guidance gaps, particularly in relation to promoting a shared understanding of child wellbeing and risk thresholds, and child and family service system roles and responsibilities in relation to child wellbeing. |

| Recommendation ES 4 Strengthening capacity of phase one workforces |

|---|

| That change strategies and ongoing training of information sharing entities related to the information sharing reforms continue to develop capacity among Phase One prescribed workforces and to facilitate integration of practice between Phase One and Phase Two prescribed workforces. This could be facilitated through workforce forums developed in collaboration with peak/lead bodies, and through support for local and place-based networks across sectors and promotion of local champions. |

Embedding the CIS Scheme in policies and guidelines

Given the complexity and legislative requirement for implementation of the CIS Scheme it has been important for prescribed organisations and services to ensure that internal policies and guidelines support their workforces in the appropriate sharing of information. Among prescribed workforces surveyed in 2019 who identified that their organisations did have policies on sharing child information prior to commencement of the CIS Scheme, there was mixed perceptions of the policies’ currency and value in enabling information sharing. Change at follow up survey in 2020, however, included a larger proportion of respondents reporting that the policies were up to date (85%, an increase from 65%), were sufficiently flexible and provided clear guidance on permission to share. There was a reduction in the perception that policies sometimes hinder early identification of needs or prevention of issues.

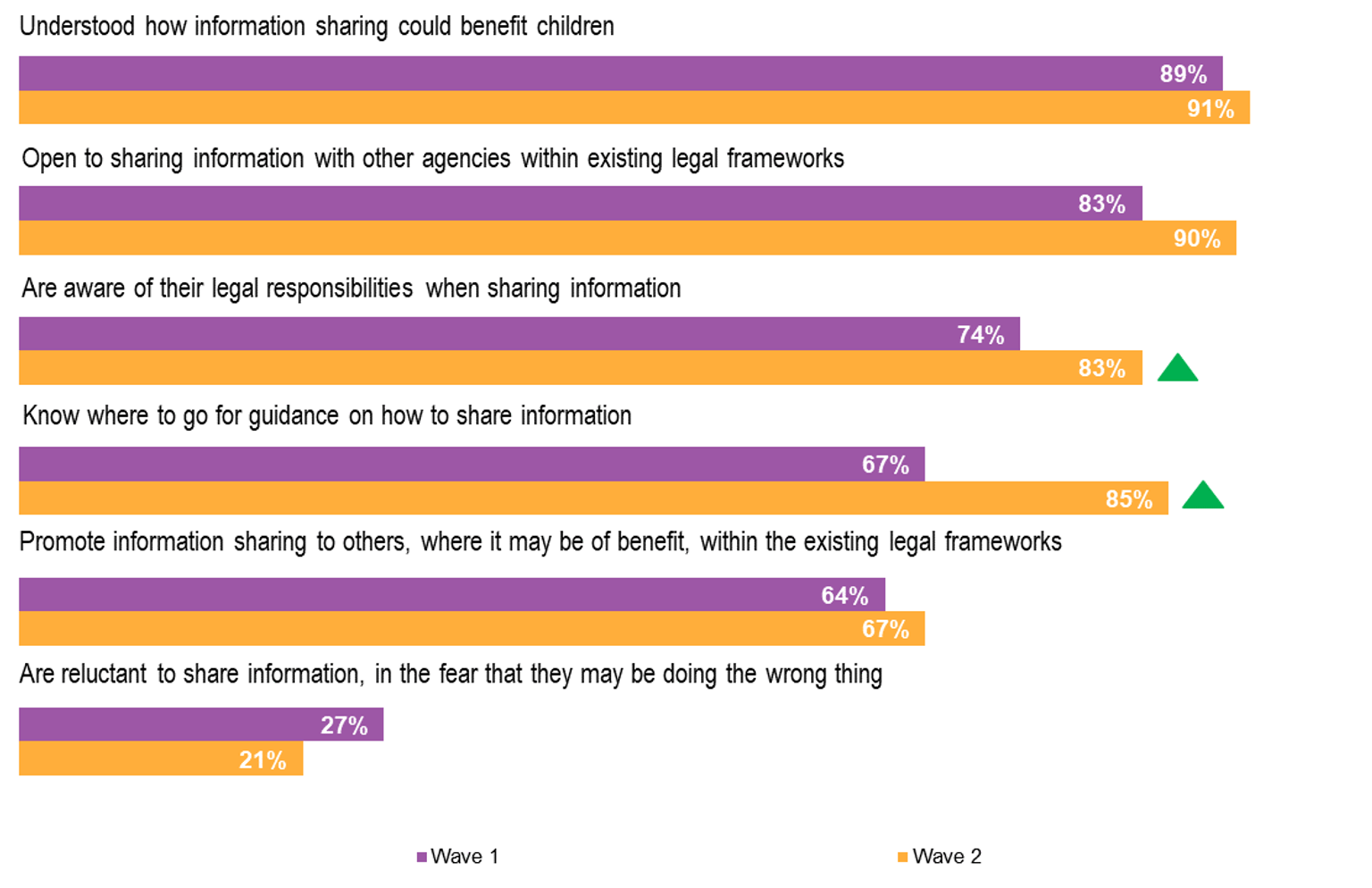

In relation to their understanding of how to share information, there was an increase in survey respondents who considered that they were aware of their legal responsibilities (from 74% prior to commencement of the scheme to 83% at follow up in 2020) and who knew where to go for guidance on information sharing (from 67% to 85% at follow up).

While there are positive indications of an improved level of workforce understanding of, and receptiveness to information sharing, there is a continuing conservative position regarding willingness to promote information sharing where it may be of benefit. This position supports stakeholder feedback about the evolving nature of the culture change that needs to occur and the further work to be done to embed the CIS Scheme in practice.

Information sharing entity systems and processes support monitoring of implementation of the CIS Scheme

Prescribed organisations and services were expected to leverage their existing systems to meet the record keeping requirements under the CIS Scheme. A selection of prescribed organisations and services were asked about whether there had been a need to make changes to their record keeping systems in anticipation of, and subsequent to introduction of the CIS Scheme.

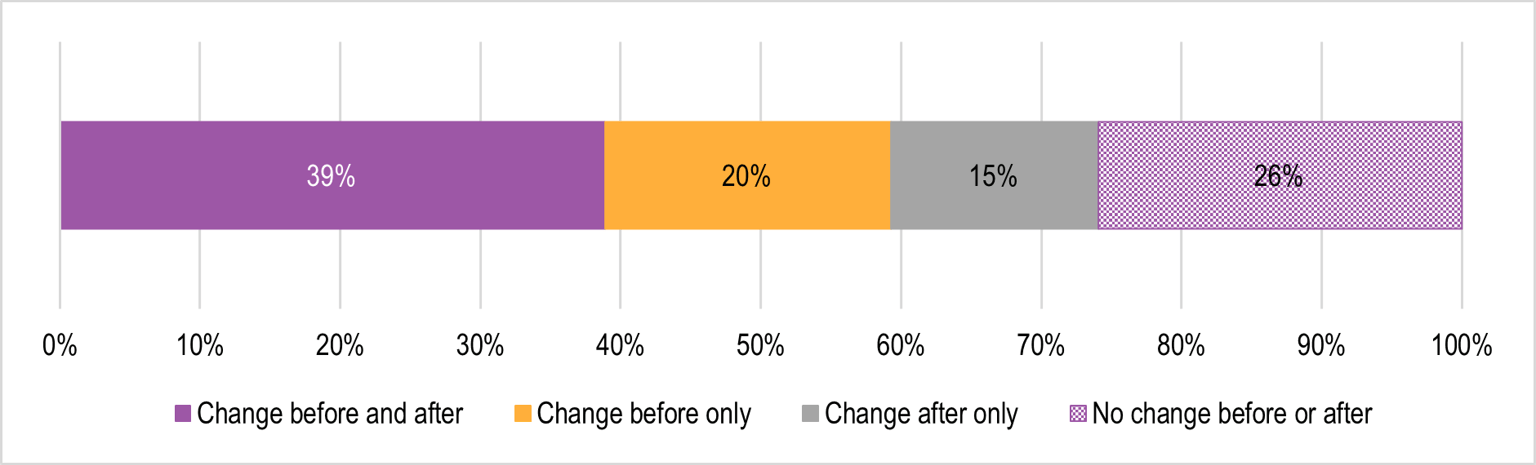

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of organisations (n=54) indicated that changes had been made to record keeping arrangements in response to the CIS Scheme. Some of the changes made in preparation for the CIS Scheme included developing forms, improving and updating processes, updating client management systems, improving data protection processes, and developing spreadsheets to hold new information.

The Ministerial Guidelines[1] provide a list of required information for record keeping, which is set out in the Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018. Organisations surveyed in 2019 about their record keeping were asked about the extent to which they adhered to the list of required information in relation to each of the key activities in information sharing. Required information relating to the category of receiving a request had the highest rate of compliance with 74% of respondents reporting that all mandatory items were recorded. The remaining categories relating to information requirements for responding to a request, voluntary disclosure, and receiving and responding to a complaint, had an appreciably lower level of full compliance.

Required information for record keeping provides information sharing entities with an important source of internal monitoring of effective implementation of the CIS Scheme and an ability to assess any improved outcomes for children and their families. If capacity allows, the information collected by information sharing entities could potentially be aggregated by government to enable measurement of the contribution of the CIS Scheme to the intended outcomes, such as earlier intervention and prevention.

| Recommendation ES 5 Compliance with record keeping requirements |

|---|

| That CIS Scheme partner government departments work with information sharing entities in their respective sectors to promote compliance with the legislated record keeping obligations under the CIS Scheme, as explained in the Ministerial Guidelines. |

More recent feedback from prescribed organisation and services highlights ongoing refinement of processes and tools to support the information sharing entity’s commitment to taking responsibility for children. This has included amendment to intake forms for services that deal predominantly with adults to record any involvement of children and consent forms that raise client awareness of information sharing schemes.

A consistent conversation across services to ensure that service users are aware of and understand the information sharing reforms is important to effective implementation of the CIS Scheme and the ongoing process of engagement with service users and consumers (individuals, families and communities) more broadly.

| Recommendation ES 6 Service User Awareness |

|---|

| That training modules and templates identify information sharing entity responsibility for, and provide resources to support a consistent approach to service user awareness of the information sharing reforms and ensuring they understand their implications, the obligations of information sharing entities and the service user’s rights. |

There was little change reported by workforces in their perception of the level of effort needed to align their organisation’s practices, procedures and systems to the CIS Scheme over the period of the two workforces surveys. The average ranking of level of effort was 6.2 at baseline and 6.4 at follow up (0=very little effort and 10=extremely high level of effort; n=194). This result supports qualitative feedback from stakeholders that adjusting systems to the CIS Scheme has been ongoing in the period since commencement of the CIS Scheme, and that for many organisations, this has not been an inconsiderable effort.

Enablers and barriers to implementation

A wide range of enablers to effective implementation of the CIS Scheme through ensuring workforce skills and knowledge were cited by information sharing entities. These included:

- building workforce understanding of the legislative basis for information sharing to improve confidence in applying the CIS Scheme

- having an identified person with responsibility for implementation of the CIS Scheme

- translation of policy into practice including alignment with other policies, frameworks and guiding principles

- promotion of ongoing (experiential) learning through communities of practice.

Insights into barriers to effective implementation of the CIS Scheme because of a lack of workforce capability are provided by workforces surveyed in 2020 about the main reason for not requesting information. This largely derives from insufficient knowledge of the CIS Scheme. Other challenges experienced included:

- lack of practice in applying a child-focus

- lack of familiarity with the culture of other organisations

- privacy perceptions.

Activities delivered by information sharing entities to enable practice change

A range of innovative approaches have been developed by prescribed organisations and services to support practice change among their workforces. This has involved embedding training in relevant existing training programs, making the language around the CIS Scheme more accessible, enabling awareness of children in their work, and identifying professionals/leaders available for secondary consultations.

There should be a process for capturing and disseminating examples of approaches to supporting workforce practice change, such as the potential for proactive sharing. At a minimum, this could be demonstrated through a series of case studies that have regard for the structure, size and location of organisations and services.

| Recommendation ES 7 Disseminating approaches to practice change |

|---|

| That good practice case studies across a range of contexts be identified and shared through a variety of media, including through innovation workshops and published material. |

Achievement of intended outcomes

A number of positive outcomes were achieved in the implementation of the CIS Scheme. These included a perception among workforces that legal restrictions and organisational policies that inhibited information sharing had decreased, and that they were less likely to refuse a request for information after the introduction of the CIS Scheme. Privacy was also less likely to be cited as a reason to be used for refusing requests for information.

There were also early signs of cultural shift among workforces towards early intervention and prevention. Evidence provided by stakeholders indicated a greater willingness of their workforce to consider information sharing in cases which would have been perceived as not of sufficient concern to warrant information sharing prior to the CIS Scheme. Workforces were also beginning to look beyond their traditional sources of information to consider how other sources of information could supplement their case assessment and planning. However, these efforts were sometimes curtailed by the fact that workforces were not necessarily aware of who to seek information from, or with which services it would be appropriate to share information.

There was also evidence that workforces from different sectors were collaborating and coordinating better as a result of the CIS Scheme. Collaborative activities were evidenced at a broad range of levels, including between peak/lead bodies, leadership of individual prescribed organisations and services, and among individual workers.

It will be important to continue to enable Phase One secondary and tertiary services to actively seek opportunities to participate in child information sharing for purposes of promoting child wellbeing and safety. The implementation of Phase Two of the CIS Scheme should include strategies to strengthen existing and new efforts to leverage from the engagement with families and children of secondary and tertiary services, to optimise the extended support that might be available for shared clients.

| Recommendation ES 8 Role Clarity in collaborative practice |

|---|

| That the implementation of Phase Two of the CIS Scheme includes strategies to strengthen collaboration between universal, secondary and tertiary services (that is, Phase One and Phase Two information sharing entities) around a child, to optimise benefits for the child, and to reinforce the contribution of Phase One prescribed workforces. |

In relation to the level of information sharing activity, as there is no systematic reporting of information sharing activity, and there are numerous informal ways to share information, it was not possible to conclude at this time whether the implementation of the CIS Scheme had made an impact on the level of information sharing.

In relation to individual child outcomes, it was too early to say whether the CIS Scheme had made a significant impact. While there were some examples of good practice, the data available did not provide a clear indication of positive outcomes for individual children. However, stakeholders felt confident that the CIS Scheme provides a strong foundation for improved outcomes for child wellbeing and safety.

While the achievement of some early outcomes is promising, stakeholders also provided feedback that the CIS Scheme is not a simple implementation of a policy or program, but rather requires a paradigm shift in the way services consider the needs of the child in their everyday practice. Continued support and education will be necessary to achieve this cultural shift and embed child-focused practice across all sectors of service delivery.

Unintended adverse impacts

Stakeholders who participated in the data gathering activities occasionally raised unintended impacts of the CIS Scheme, which were predominantly either positive or neutral. There were a small number of unintended adverse impacts that relate to perceived disruption to previous workable arrangements for information sharing. Generally, however, the perceived impacts could be considered short term disruption to pathways for information sharing with a view to enhancing the quality and extent of information sharing through a more rigorous and transparent process.

Most stakeholders appreciated that the CIS Scheme augments the information sharing capabilities of information sharing entities. However, the fact that the CIS Scheme augments, rather than replaces, any existing information sharing processes or standards (such as the Child Safe Standards, Mandatory Reporting Requirements or Reportable Conduct Scheme) should continue to be reinforced through ongoing education and communications.

| Recommendation ES 9 Clarifying relationships to other legislation and standards |

|---|

| That consideration be given to providing material to reinforce how the CIS Scheme interacts with other existing legislation and standards, such as the Child Safe Standards, Mandatory Reporting Requirements and Reportable Conduct Scheme, and how these relate to information sharing entities in different sectors, to ensure adherence to the intent of mechanisms available to facilitate child information sharing. Such an approach can highlight where the CIS Scheme provides additional information sharing powers over existing legislation and standards, providing clarity on when and how to use the CIS Scheme. |

While the potential for inappropriate use of the CIS Scheme was a concern raised by stakeholders at commencement of the CIS Scheme, there were no examples of inappropriate use or complaints arising out of implementation of the CIS Scheme encountered during the data collection for this Review. Nonetheless, this continues to remain a risk and the potential for inappropriate use should be actively monitored at organisational and state-wide levels.

Success of prescription of information sharing entities

In considering the impact of the proposed information sharing reforms, it was intended that the phased implementation of the CIS Scheme would involve both government and non-government organisations and align to implementation of the FVIS Scheme to reduce any confusion amongst the workforce and community. The significant overlap of workforces prescribed under both information sharing schemes has provided a logical framework for integrated training but has also highlighted practices that can be strengthened to ensure the successful implementation of the CIS Scheme. Lessons identified by respondents to the follow up workforces survey include reinforcing the importance of routinely gathering accurate information, formalising standards for information collection and developing processes for documenting information sharing occasions and outcomes. Some respondents indicated that they would have liked prescription of information sharing entities to be broader to widen the opportunities for earlier intervention and prevention, however, there was recognition of the increased level of effort that would have been required and the potential for other barriers to have been created to effective implementation.

It could be expected that initial engagement of Phase One information sharing entities in the CIS Scheme will ensure that these services, acutely aware of how unsustainable downstream support is and the impact of entrenched and intergenerational disadvantage, can champion prevention and earlier intervention initially within secondary and tertiary services and ultimately among services operating across the continuum of care. Further support and time is required to ensure that Phase One information sharing entities fully operationalise the CIS Scheme and can work effectively with an expanded CIS Scheme to improve equity of outcomes for children and young people.

Impacts of the CIS Scheme on diverse and disadvantaged communities

The CIS Scheme forms part of a larger toolkit available to information sharing entities to promote the wellbeing and safety of all children in Victoria, with an emphasis on targeted supports for disadvantaged populations. There are a wide range of Commonwealth and Victorian policies, guidelines and frameworks that support the design of services, including workforce knowledge and skills, to respond to the needs of diverse populations with a view to improving access to specialist and mainstream services. Change through service provider policies and practices aims to reduce discrimination, embed cultural responsiveness, foster social inclusive practices, offer healing and trauma informed care and access to language services. It could be expected that the extent of the impact of the CIS Scheme on diverse and disadvantaged communities will be in part a measure of how well the CIS Scheme is utilised and in part reflective of how well services are engaging with diverse communities. The ability to monitor and evaluate the impact of the CIS Scheme on outcomes for diverse and disadvantaged communities will require a more rigorous approach to data collection.

| Recommendation ES 10 Measuring contribution of the cis scheme in responding to the needs of diverse and disadvantaged communities |

|---|

| That CIS Scheme partner government departments consider the adequacy of the current minimum record keeping requirements of the CIS Scheme, including as they inform the role of the CIS Scheme in responding to the needs of diverse population groups. |

| Recommendation ES 11 Engaging diverse and disadvantaged communities |

|---|

| That CIS Scheme partner government departments engage diverse and disadvantaged groups through sector and advocacy peak bodies and information sharing entities, to understand any specific barriers to the implementation of the CIS Scheme and use these findings to assist information sharing entities to overcome these barriers. |

Implementing the CIS Scheme for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

While Aboriginal[2] stakeholders consulted as part of this project broadly expressed support for the CIS Scheme, a key issue reported in the successful implementation of the scheme for Aboriginal community controlled organisations (ACCOs) has been barriers related to lack of trust among community members because of the legacy and abiding harm of past experiences relating to child services. There is a need, therefore, to continually educate and reassure families and communities on the objectives and intended outcomes of the CIS Scheme. However, this requires a significant investment of time and effort from the ground up, beginning with the development of culturally appropriate resources for the CIS Scheme.

While stakeholders were cautious about the pace of implementation of the CIS Scheme among Aboriginal organisations and service providers, they were also confident that the CIS Scheme will lead to better outcomes for Aboriginal women and children.

| Recommendation ES 12 Cultural safety |

|---|

| That CIS Scheme partner government departments continue to work with and support the Aboriginal service sector to provide community engagement to ensure Aboriginal communities have a good understanding of the CIS Scheme, and to ensure that cultural safety is taken into account at all stages of using the CIS Scheme. |

| Recommendation ES 13 Culturally appropriate resources to support implementation of the CIS scheme in Aboriginal communities |

|---|

| That CIS Scheme partner government departments work with Aboriginal lead bodies to develop culturally appropriate training and support materials for the effective implementation of the CIS Scheme in Aboriginal communities, both by Aboriginal-specific and mainstream information sharing entities. |

[1] Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines. Guidance for information sharing entities. State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services, September 2018. Available at www.infosharing.vic.gov.au

[2] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may be also referred to in this report as Aboriginal people

1. Introduction

Introduction to the Child Information Sharing Scheme Two-Year Review report.

1.1 Background

Accountability for child wellbeing and safety

Independent reviews and inquiries conducted in Victoria in the period 2011 to 2016 relating to child safety and wellbeing have consistently highlighted a lack of information sharing among service providers as a significant barrier to effective and timely support for vulnerable families, and especially children[3]. Issues identified have included:

- development of a risk-averse culture to sharing information fostered by the complexity of multiple legislative frameworks

- inability of professionals to obtain a full understanding of a child’s circumstances when information held by other service providers is not shared, potentially delaying a timelier intervention and the possibility of avoided need for secondary and tertiary services

- difficulty in knowing whether a child is participating in universal or targeted services because this information is not readily accessible.

The Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence (2016) found that an uncoordinated approach to risk assessment and risk management of family violence cases had negative impacts that extended to women and their children. The Commission recommended a specific family violence information sharing scheme and the development of evidence-based risk factors specific to children for inclusion in a revised risk assessment framework.

At a national level, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017) (the McLellan Royal Commission) also found that institutions with responsibilities for children’s safety and wellbeing did not share information with other institutions or organisations or failed to do so in a timely and effective manner. While existing legislation provided for a degree of information sharing to protect the safety of children, barriers to sharing information included complex rules and guidelines, concerns about privacy and confidentiality. A national information exchange scheme was recommended that provides for prescribed bodies to share information and included the establishment of an information sharing scheme within each jurisdiction. Victoria’s Child Information Sharing Scheme is modelled on the recommendations of the McLellan Royal Commission.

Policy context

Consistent with the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Family Violence, the first steps to build a better future for Victorian children, young people and families are set out in the Roadmap for Reform: strong families, safe children. The reforms seek to drive change in the child and family services system that emphasises early intervention, prevention and sharing responsibility. Information sharing is described as a key enabler for other reforms, including the identification of risk factors that are specific to children and the provision of specialist supports and services for children and young people. The Roadmap aims to create services that are coordinated and work together noting that:

…Child protection and family support services are not well connected to universal health and education services. Nor are they well connected to targeted adult services such as specialist family violence, mental health and drug and alcohol services. Poor communication between agencies delays active engagement of, and rapid responses to, families at risk..[4]

The Roadmap reforms complement other key policies in Victoria including the Education State reforms introduced in 2015. These reforms aim to develop a quality education system that is available to all students regardless of their background or circumstances. The Education State Early Childhood Reform Plan is providing targeted support to disadvantaged children in realising a more ‘equitable and inclusive’ early childhood system.

Child Information Sharing Scheme

There are a range of existing information sharing permissions and obligations relating to the safety of children. The CIS Scheme expands the circumstances in which professionals and organisations can share information relating to the wellbeing or safety of children. The CIS Scheme is mandated under Part 6A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 to enable prescribed entities to share confidential information in a timely and effective manner in order to promote the wellbeing and safety of children[5]. Part 6A was proclaimed in September 2018. Prescribed entities are referred to as information sharing entities[6] (ISEs) that are authorised organisations and services including authorised frontline practitioners, specified by the Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018.

Under the CIS Scheme, ISEs are authorised to request confidential information from another ISE, and to disclose information to another ISE, either voluntarily or in response to a request if in their professional judgement they identify that the CIS Scheme threshold is met. The threshold or legal requirements of the CIS Scheme is made up of three parts:

- confidential information is being requested or disclosed to promote the wellbeing or safety of a child or group of children

- sharing confidential information will assist in making a decision, assessment or a plan, and/or the conduct of an investigation, and/or providing a service, and/or managing any risk to a child or group of children

- information being requested or disclosed is not known to be ‘excluded information’ under the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 (and is not restricted from sharing by another law).[7]

ISEs must comply with requests for information that meet the three parts of the threshold.

Legislative principles in the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 provide guidance to ISEs in the application of the legislation. The principles include that ISEs should:

- give precedence to the wellbeing and safety of children over the right to privacy

- share information only to the extent necessary to promote the wellbeing or safety of a child, consistent with their best interests

- work collaboratively and respect the functions and expertise of other ISEs

- seek to maintain constructive and respectful engagement with children and their families.

Ministerial Guidelines relating to the operation of the CIS Scheme include how the principles are to be applied in practice by an ISE.

Child information[8] sharing reforms also provide for the establishment of a web-based Child Link Register under Part 7A of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005, proclaimed in February 2019. The Register is currently under development and will streamline access by authorised professionals to information about participation in government-funded programs of children born in or resident of Victoria.

It is expected that the child information sharing reforms will[9]:

- Improve early needs and risks identification and support, by permitting professional and respectful sharing of information early

- Change a risk averse culture in relation to information sharing, in part by simplifying the legislation

- Increase collaboration and integration between child and family services, promoting shared responsibility across organisations that provide services to children and families

- Support children’s and their families’ participation in services to which they are entitled.

The CIS Scheme operates alongside family violence prevention initiatives introduced for a similar purpose of supporting effective sharing of information between organisations. The Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (the FVIS Scheme) and the Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) are provided for under the Family Violence Protection Act 2008. The FVIS Scheme enables information sharing to facilitate assessment and management of family violence risk to children and adults, and the MARAM guides information sharing under both information sharing schemes where family violence is present. Where family violence is believed to be present and a child is at risk, information sharing entities will use the FVIS Scheme to assess and manage family violence risk to both children and adults, as well as the CIS Scheme to share information to promote the child’s wellbeing and/or other aspects of their safety.

Consistent with the recommendation of the McLellan Royal Commission, a phased approach has been adopted to introduction of the CIS Scheme with the intention of minimising the burden of organisational change and maximising organisational readiness. The first tranche of workforces prescribed under the CIS Scheme was proclaimed on 27 September 2018, referred to as Phase One, and comprised approximately 28,000 workers representing around 700 entities primarily within the secondary and tertiary sectors[10]. Phase One information sharing entities generally already had high level permissions to share information about children and families and the impact of extending these permissions under the CIS Scheme was expected to be minimal. Exceptions included services working predominantly with adults such as statutory mental health services, alcohol and other drugs services and housing. Phase Two will extend the CIS Scheme to key primary and universal services in education, health and justice sectors and will commence on 19 April 2021. As for Phase One, this next phase will include information sharing entities prescribed under both information sharing schemes. The Phase Two expansion is estimated to involve an additional 370,000 workers in 7,500 prescribed entities[11].

Governance arrangements for the CIS Scheme reflects a multi-agency approach consistent with the legislative intent and responsibility for the suite of information sharing reforms. Initial oversight for the implementation of the reforms, including the CIS Scheme was provided by the Information Sharing and MARAM Framework (ISMARAM) Steering Committee supported by an Interdepartmental Committee and a Working Group. New governance arrangements came into effect in July/August 2020 disbanding the ISMARAM Steering Committee and establishing the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS) Steering Committee. Representation on the CISS Steering Committee, convened by DET, includes DHHS, FSV, DJCS, VicPol, Courts Victoria, Department of Treasury and Finance and Department of Premier and Cabinet. The new arrangement provides a strengthened focus on CIS Scheme implementation for a significantly expanded group of professionals and services in 2021. With disbandment of the ISMARAM Steering Committee, Family Safety Victoria (FSV) has established the MARAM and Workforce Directors Group.

1.2 Purpose of this review

An independent review of the operation and any adverse impacts of the CIS Scheme within two and five years of commencement is required under section 41ZN of the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005. This review represents the two-year review of the CIS Scheme covering the period September 2018 to September 2020.

The two-year review was required to:

- Determine to what extent the CIS Scheme has been implemented effectively.

- Identify key enablers and barriers to implementation.

- Determine to what extent the CIS Scheme is achieving its intended outcomes.

- Consider and identify any adverse impacts of the CIS Scheme.

- Assess the success of the prescription of Information Sharing Entities.

- Assess impacts on diverse and disadvantaged communities.

- Include recommendations (as necessary) on any matters addressed in the review.

1.3 Baseline report

As part of the Two-Year Review, a baseline report was produced for the purposes of assessing any change in information sharing attitudes and practices associated with implementation of the CIS Scheme in the first two years of operation. The baseline report, compiled in the latter half of 2019 and delivered in December 2019, focused on the extent of information sharing among prescribed workforces[12] related to the wellbeing and safety of children and young people prior to introduction of the CIS Scheme. It also considered record keeping systems in place for information sharing and the implementation support provided to prescribed workforces by peak/lead bodies.

As the CIS Scheme had been in operation for approximately 12 months at the time of collecting baseline information, stakeholders were also given the opportunity to provide feedback on their early experience of adjusting to the CIS Scheme.

The key points from the baseline report are provided at Appendix A.

Analysis of data collection from prescribed workforces obtained in the latter half of 2020 focuses on feedback from those who also completed the baseline data collection enabling an understanding of how sentiments and attitudes changed following commencement of the CIS Scheme. Perceived progress, new developments, and any continuing issues for Phase One prescribed entities was also obtained from follow-up consultation with peak/lead sector bodies and key informant government agencies. Further information about the review methodology is provided in Chapter 2.

1.4 Impact of COVID-19

The coronavirus pandemic and associated restrictions to manage the transmission of the virus in Victoria coincided with the final round of data collection for this review. The impact on the community and service providers has been profound affecting service delivery and placing significant pressure on many of the secondary and tertiary services involved in operation of the CIS Scheme that are in the health, human services, justice and police sectors. The review methodology was adapted to accommodate the changed circumstances and the need for a longer research period to enable stakeholder engagement. These changes minimised the impact on engaging stakeholders in the review, with the exception of young people.

However, there has been disruption to initiatives to continue to embed the information sharing reforms into organisations and services while other priorities have required attention[13]. This review also highlights sector concern that the health and economic impact of the pandemic is having a real impact on children and young people that will require a collective response to keep children safe.

1.5 Two-Year Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme

An independent review of the FVIS Scheme overlapped with this review of the CIS Scheme, both in terms of timing and prescribed organisations and services. The FVIS Scheme review covered the first two-years of operation of the FVIS Scheme which involved an Initial Tranche of entities prescribed in February 2018 and Phase One entities prescribed in September 2018. The review was tabled in Parliament in August 2020[14]. Many of the recommendations of the review, whilst seeking to ensure effective future expansion of the FVIS Scheme, resonate with findings of this review and could be expected to also benefit application of the CIS Scheme by both Phase One and the planned Phase Two prescribed organisations and services. These recommendations address shared issues such as:

- clarifying privacy issues

- monitoring impacts of the information sharing reforms on Aboriginal people to avoid any adverse effects

- providing additional support for the work of Aboriginal organisations to enable appropriate application of information sharing reforms

- ensuring timely delivery of quality training to workforces to be prescribed under Phase Two

- facilitating application of the information sharing reforms through use of case studies

- continuing the information sharing Enquiry Line and sector grants.

It is noted that all recommendations arising from the findings of the FVIS Scheme review have been supported in full or in-principle by the Victorian Government.[15]

Generally, where there was evidence that the subject of these recommendations have or are to be addressed (such as timing of training for workforces to be prescribed, improving understanding of privacy issues), they have not been pursued further in this report as specific recommendations.

1.6 Structure of this report

The review report is structured around the key areas of inquiry set out under the above section 1.2. A series of indicators provided the context for exploring these areas and were set out in an evaluation framework developed for the review. The context guiding discussion of each of the areas of inquiry introduces the relevant chapters.

[3] Includes reports from Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, Commission for Children and Young People and Coroners Court of Victoria

[4] Roadmap for Reform: strong families, safe children. State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services, April 2016. p.12

[5] ‘Child’ is defined as a person who is under the age of 18 years and an unborn child that is the subject of a report made under section 29 of the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 or a referral under section 32 of that Act.

[6] Information sharing entities may also be referred to in this report as prescribed professionals and services, and prescribed workforces.

[7] Child Information Sharing Scheme Ministerial Guidelines. Guidance for information sharing entities. State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services, September 2018.

[8] In this report, reference to ‘child information’ is used in the context of sharing information to promote child wellbeing and safety. Information shared may be about an adult or a child.

[9] Child Information Sharing Reform Background and Overview. Department of Education and Training. Victoria State Government.

[10] Department of Education and Training (2019). Child Information Sharing Scheme Regulatory Impact Statement, Amendment Regulations 2020. Victoria State Government.

[11] Ibid

[12] For the purposes of this report, ‘prescribed workforces’ refers to workforces in agencies, organisations and services prescribed under the CIS Scheme

[13] Only 58% of prescribed workforces surveyed in 2020 responded that there was no change to child information sharing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

[14] McCulloch J., Maher, J., Fitz-Gibbon, K., Segrave, M., Benier, K., Burns, K., McGowan, J. and N., Pfitzner. (2020) Review of the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme Final Report. Report to Family Safety Victoria. Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Faculty of Arts, Monash University.

[15] The Victorian Government response is available at: https://www.vic.gov.au/government-response-review-family-violence-information-sharing-legislative-scheme

2. Methodology

Methodology of the Child Information Sharing Scheme Two-Year Review report.

2.1 Approach

A mixed method approach was applied to this review to obtain information from a variety of new and existing sources about operation of the CIS Scheme in the first two years since commencement of the whole-of-Victorian-government initiative. The review, commissioned by the Department of Education and Training (DET) as lead agency for the CIS Scheme, was conducted by ACIL Allen Consulting in partnership with Wallis Market and Social Research (Wallis).

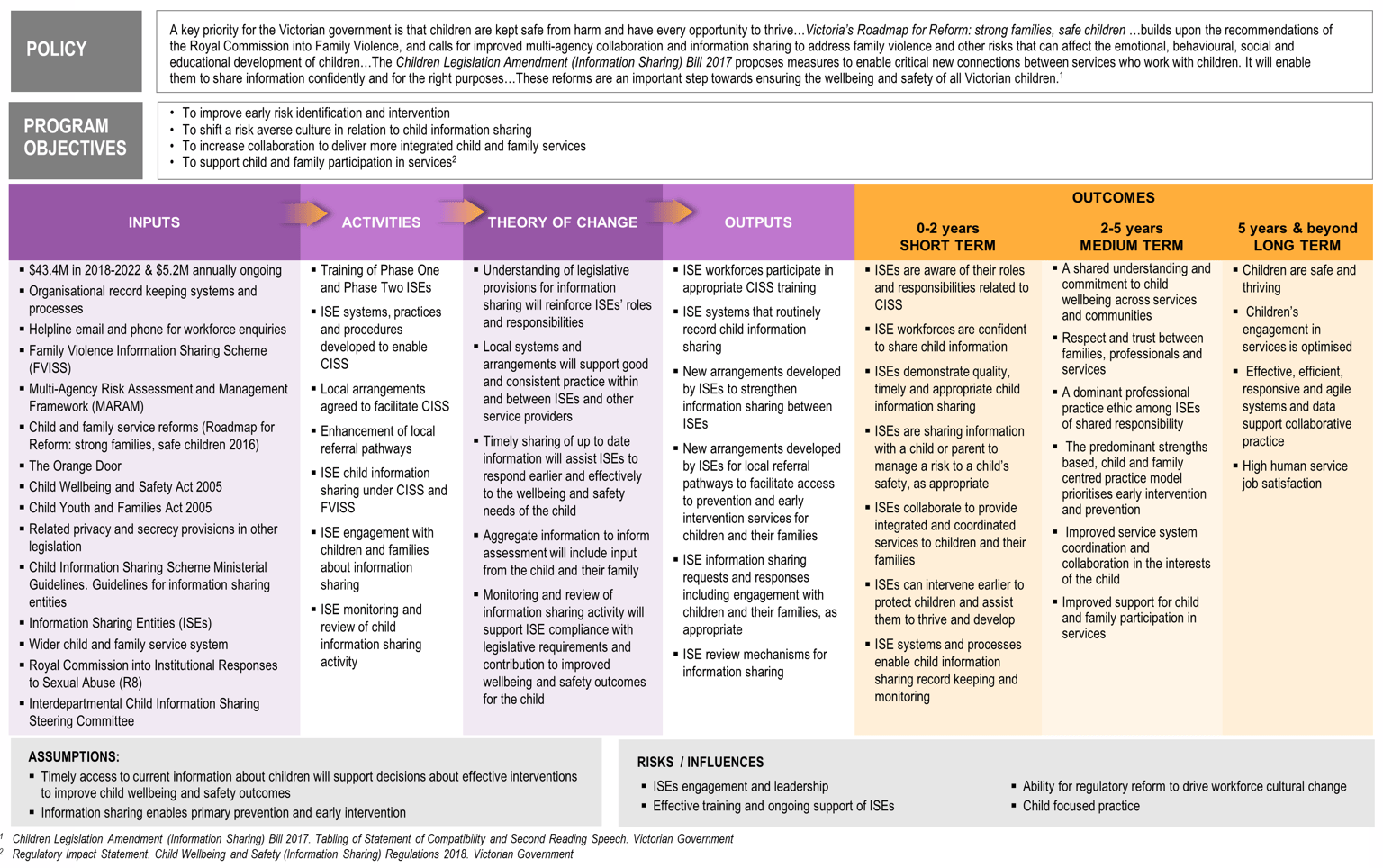

The approach to the review was underpinned by development of a program logic for the CIS Scheme providing an overview of the key inputs, outputs and expected outcomes of the CIS Scheme (see Appendix B). Alignment of the program logic and the key areas of inquiry for the review underpinned the research questions in the evaluation framework that has guided this review. The framework identified measures and potential sources of information to inform a response to each of the research questions.

Data collection was undertaken predominantly at two points in time with the first commencing in July 2019 (providing input to the Baseline Report) and the second in June 2020. Information gathering focused on establishing attitudes and practices of prescribed workforces to information sharing, the support provided by peak bodies to their respective sectors for effective implementation of information sharing reforms and the extent of change to organisational record keeping processes and systems to facilitate implementation of the CIS Scheme.

Ethics and other research approvals were obtained for engagement with prescribed workforces and planned consultation with young people accessing services provided by information sharing entities under the CIS Scheme. Accessing the views of young people supported by information sharing entities is discussed under section 2.3 relating to limitations of the review.

2.2 Review inputs

Data collection methods included surveys, interviews, virtual workshops, document review and case studies illustrating aspects of implementation of the CIS Scheme. Tools developed for the review included questionnaires, discussion guides and background material to facilitate workshop discussion.

A summary of data collection activities is provided in the following table. A profile of respondents to the workforces surveys is provided at Appendix C. Copies of data collection tools are provided at Appendix D.

| Activity | Stakeholder | Purpose | Participation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 data collection (Wave 1) to inform the Baseline Report | |||

| Surveys | Phase One prescribed ISE workforces drawn from ‘sharers’ and ‘leaders’ who attended training | To explore attitudes and practices related to information sharing prior to commencement of the CIS Scheme | 319 survey respondents |

| Phase One prescribed ISE organisations | To assess the extent of organisational change to systems and processes to enable operation of the CIS Scheme | Senior representatives responding on behalf of 76 government and non-government ISEs providing services in Phase One under the CIS Scheme | |

| Interviews | Key informants | To obtain background about departmental/agency roles and responsibilities in relation to the CIS Scheme |

Department of Education and Training (DET) Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Family Safety Victoria (FSV) Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS) Victoria Police (VicPol) Court Services Victoria (CSV) |

| Peak/lead bodies | To investigate support for sector implementation of the CIS Scheme and explore sector feedback on information sharing reforms |

Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare Commission for Children and Young People Victorian Council of Social Services Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency Cooperative Ltd Council to Homeless Persons Domestic Violence Victoria Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association |

|

| Phase One prescribed ISE workforces | In-depth follow up on questions raised in the workforces survey | 15 respondents, drawn from those who participated in the survey | |

| 2020 follow-up data collection (Wave 2) to inform the Two-Year Review | |||

| Survey | Phase One prescribed ISE workforces | To explore attitudes and practices related to information sharing after commencement of the CIS Scheme |

244 survey respondents of whom 194 participated in the 2019 survey |

| Interviews | Key informants | To obtain an update on departmental/agency roles and responsibilities in relation to the CIS Scheme | DET / DHHS / FSV / DJCS / VicPol / CSV |

| Peak/lead bodies | To update support for sector implementation of the CIS Scheme and sector feedback on information sharing reforms | As for 2019 data collection | |

| Virtual workshops | Phase One prescribed ISE organisations and services | To share experiences of implementing the CIS Scheme, discuss the outcomes and benefits of the CIS Scheme and explore future collaboration to further strengthen implementation of the CIS Scheme | Two workshops attended by a total of 19 participants from two government organisations (representing five different business units) and representatives from 11 non-government organisations delivering government funded services across both regional and metropolitan locations. Services represented included Child Protection, out-of-home care, integrated family services, Child FIRST, Maternal and Child Health, mental health, alcohol and other drugs services, homelessness services, specialist family violence services, victim support services, youth justice and Births, Deaths and Marriages |

Source: ACIL Allen Consulting 2020

To the extent appropriate, quotations used in this report and drawn from qualitative feedback provided as part of the surveys of prescribed workforces may include identification of the respondent’s workforce category to provide additional context.

2.3 Limitations

The review methodology has been adapted to accommodate scheduling changes related to roll out of the CIS Scheme and the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on Phase One prescribed organisations and services.

Establishing a baseline

A key component of establishing a baseline related to information sharing was the survey of prescribed workforces. Recruitment of workforces to this research was linked to their online registration for initial training related to the information sharing reforms. Workforces were surveyed for baseline attitudes and practices approximately 10 months after the CIS Scheme had been proclaimed, in part due to a delay in commencement of training. To accommodate this timing, survey respondents were asked to consider their attitudes and practices to information sharing 12 months previously, prior to introduction of the CIS Scheme.

Workforce survey sample

There are two possible areas of limitations caused by bias in the sample of workforces participating in the 2019 and 2020 surveys, namely non-response bias among the survey sample and sample bias. Non-response bias, where those responding to the survey invitation fundamentally differed from the overall population, is likely to have been mitigated as a serious source of bias by the relatively high response rates achieved and the use of the multi-modal approach (option for participants to complete the survey by telephone or online). In relation to sample bias, as the sample of workforces opted in to the research, they could be considered more engaged with the CIS Scheme. While the likelihood of this phenomenon occurring has not been measured, it is expected that it would be limited in nature.

Progressive feedback from prescribed organisations and services

Early feedback on implementation of the CIS Scheme was intended to be captured late in 2019 through roundtables involving prescribed organisations and services, including representation from those entities expected to have been prescribed under Phase Two. Other priority consultation on the information sharing reforms at that time and deferral of prescription of Phase Two entities until 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic made this approach impracticable. Consequently, it was agreed that the planned workshops in 2020 would be augmented to provide increased opportunity for Phase One prescribed organisations and services to access this review. In the event, the impact of the coronavirus pandemic influenced stakeholder ability to participate and required the conduct of virtual workshops. Three workshops were offered and two were conducted in early August 2020.

Including the views of young people

Attempts as part of this review to provide an opportunity to hear from young people about their experiences of sharing their information were unsuccessful. This included a direct approach to eligible ISEs in the 2019 data collection period and an approach through the Centre for Excellence on Child and Family Welfare’s sector e-newsletter inviting services to obtain further information should they be willing to assist in the recruitment of young people for the 2020 data collection. The lack of response from ISEs can in part be attributed to the demands on sector resources, which were intensified in the latter part of the review during the coronavirus pandemic, and a reluctance to engage their clients in research activity.

While it has not been possible to include the voice of the young person in this research, some of the emerging benefits of the CIS Scheme are illustrated.

However, a focus on the experiences and perspectives of children and young people is even more appropriate for the subsequent five-year review of the CIS Scheme when it has become better embedded in workforce practice and its potential to support earlier intervention and prevention is realised. Future consideration could be given to support for collaboration with a selection of prescribed organisations and services and the independent reviewer for annual consultation with young people through focus groups or interview about the way in which they experience information sharing and any ways in which this experience might be improved. There may also be potential to identify ISEs who are implementing or who would agree to implement good practice record keeping (as described in the Ministerial Guidelines) when disclosing information by recording additional details about what the views of the child and/or relevant family member were about information sharing. With appropriate research approvals, this information could be reviewed for any common themes.

3. Implementation of the Child Information Sharing Scheme

This chapter addresses the following research question:

How effectively has the CIS Scheme been implemented to date?

In determining effectiveness of implementation, consideration has been given to:

- greater clarity about the circumstances in which child information can be shared

- legislative requirements for the CIS Scheme are embedded in the guidelines and processes of ISE organisations and services

- ISE workforces are prepared to consider opportunities to share child information

- ISE organisational systems facilitate retrieval, storing and recording of information under the CIS Scheme

- ISE systems and processes support monitoring of implementation of the CIS Scheme

Box 3.1 Key findings – CIS Scheme Implementation

Workforce capability

- Initial state-wide roll out of an intensive training program for Phase One prescribed workforces related to the information sharing reforms was attended by approximately 2,000 participants.

- The initial training served to create an awareness of the reforms within three months of their commencement.

- Additional training was provided by relevant government departments tailored to their respective workforces.

- Follow up support for Phase One implementation is ongoing and includes a range of learning resources and an enquiry line. There have been more than 6,000 registrations for online training.

- FSV grants to relevant peak/lead bodies have been important to extending the reach and understanding of the information sharing reforms among diverse sectors and workforces with varying experience of child-focus practice.

- Stakeholder feedback suggests there is continuing need to upskill prescribed workforces in the legislative provisions and requirements of the CIS Scheme to support effective implementation across the information sharing entities.

Consistent practice

- Further work is required to support a consistent and informed level of understanding of the threshold for application of the CIS Scheme.

- There is evidence of improved workforce attitudes to child information sharing since commencement of the CIS Scheme and preparedness to share information.

Record keeping

- While organisational policies are in place to support workforces in implementing the CIS Scheme, there may be a low level of compliance with the record keeping obligations in the Child Wellbeing and Safety (Information Sharing) Regulations 2018 and explained in the Ministerial Guidelines.

Source: ACIL Allen Consulting 2020

3.1 Greater clarity about when child information can be shared

3.1.1 Phase One prescribed workforces

As indicated at Appendix E, the majority of the Phase One organisations and services are prescribed under both information sharing schemes and the MARAM Framework. Depending on the circumstances, Phase One prescribed workforces may use either of the information sharing schemes on their own or apply both schemes where family violence is present and there are wellbeing and other safety concerns for the child/children.