- Published by:

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Date:

- 28 Aug 2025

Purpose of the Rapid Child Safety Review

On 2 July 2025, the Victorian Government announced an urgent review into child safety in early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings.

The Rapid Child Safety Review (the Review) was announced following allegations of sexual assault against children in long day care services in Melbourne. The Review has been careful to not take any actions that could interfere with live police or regulatory investigations, in-line with its Terms of Reference (see Appendix 1).

While those investigations are underway, the Review was asked to look at immediate steps the Victorian Government could take itself, and advocate for nationally, to improve child safety in ECEC in Victoria.

The Review was led by Jay Weatherill AO and Pam White PSM.

In the 6-week period, the Review focused on what will make the most difference to safeguard children in ECEC settings.

The Review has done this by considering relevant data from Victoria and other jurisdictions, research and evidence, including previous inquiries.

The Review also met with and received information from:

- experts, peak bodies, unions, providers and service leaders in early childhood education and care, including Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations

- regulators in other sectors that work with vulnerable people; and

- groups representing parents and the rights and interests of children.

For a lot of families, so much of the distress of this is that [early childhood education and care] in some form is a necessity - it is not a lifestyle preference or a sort of optional extra. We live in a society and an economy now where it is very rare for a household to stay afloat on one income. That means parents with smaller children (who don’t have parents who can step in) have to use some form of early education and care.

- A parent perspective shared with the review.

It is really important to remember that it’s not that early childhood educators are

perpetrators of abuse, it is that some paedophiles have targeted some of the gaps that

exist and exploited them. … All of the incredible early educators who are absolutely not perpetrators, … this is not about them.

- A parent perspective shared with the review.

Note to readers: The report often uses the term ‘parents’ for ease and shorthand. The Review recognises the many different family and care arrangements that support a child—including extended family members, foster, kinship, and other carers. The term ‘parent’ is intended to be inclusive of these different arrangements. While the majority of the Review’s recommendations are intended to benefit and strengthen the entire ECEC system, in the 6 weeks available, the Review has focused on the centre-based ECEC services of long day care and kindergarten. While most recommendations are applicable across the system, some will require nuanced consideration and application for family day care and outside school hours care services. |

Executive summary

Introduction

This Review was commissioned to rapidly advise the Victorian Government on what needs to change in the ECEC system to protect very young children from sexual abuse.

It is difficult to imagine the horror of the families affected by the events that led to this Review and the deep anxieties of all families who use ECEC—they have been uppermost in our thoughts as we have approached this Review.

Our recommendations are directed at:

- the steps necessary to ensure predators do not get into the ECEC system

- that if they do, we quickly detect and exclude them; and

- finally, that we make sure that they never work with children again.

It is important to note that the circumstances that led to this review are not about the vast majority of early childhood educators who are committed professionals, dedicated to the wellbeing and development of the children in their care. They also feel betrayed by these events. The active cooperation of early educators and their representatives with our Review makes this clear.

The overwhelming conclusion we have reached is that while the current market-driven model for ECEC remains, the risks to quality and safety in early childhood education and care will persist.

Findings and recommendations

The Review has identified immediate actions the Victorian Government can take to close gaps in the national ECEC system that compromise the safety of children. But the actions of Victoria alone will not fix the quality and safety issues in ECEC. Significant national action is also required to drive a system of services that deliver safe and quality education and care to the nation’s youngest children. The ECEC market has rapidly expanded. It must now be actively managed.

The Review’s 22 recommendations are set out below.

Part 1: Governments to take greater responsibility for running the ECEC system

The ECEC system exists to teach, support and help children thrive—their safety, rights and best interests are paramount. Part 1 of the report calls for all Australian Governments to adopt a more assertive and directive approach to funding and managing the ECEC system to drive quality and safety for children.

Chapter 1: Rethink the national ECEC system

The safety, rights and best interests of children must underpin all decision making in the ECEC system, from staff on the floor, right up-to the boardrooms of service providers. The National Law for ECEC should require this.

Over the past decade, the ECEC system has undergone rapid growth. This growth has occurred without a coherent plan. Rather, the market has been left to respond to financial incentives that do not drive investment in quality, safety, or in a stable and well-supported workforce.

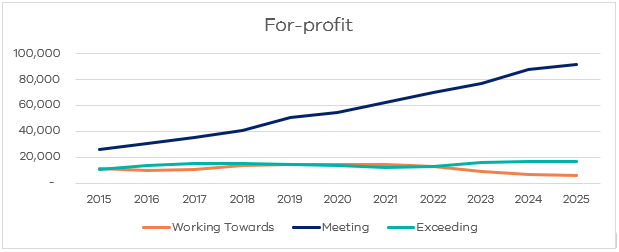

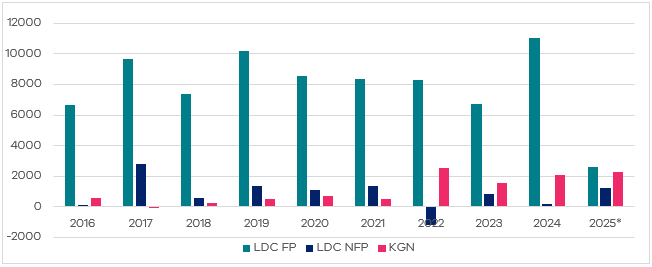

Since 2015 in Victoria, the number of long day care services has grown from 1,280 to 2,049, a 60 per cent increase. Of the 769 new long day care services in Victoria since 2015, 726 (94 per cent) are operated by for-profit providers. The rapid growth of for-profit providers in the sector has expanded the number of ECEC services, but it has also created a number of challenges for the operation and regulation of the system.

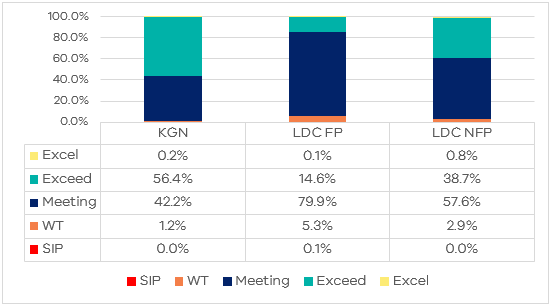

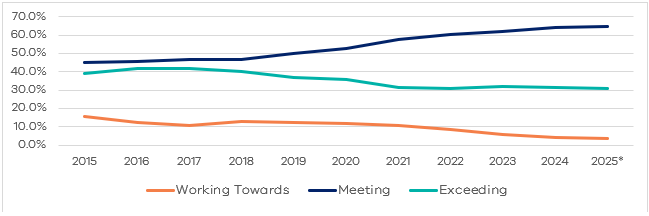

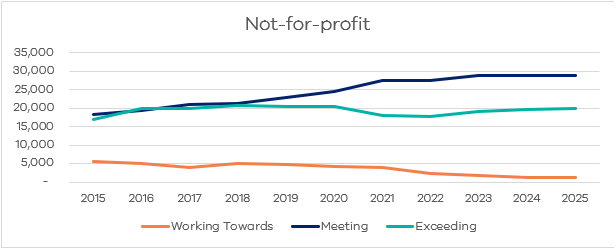

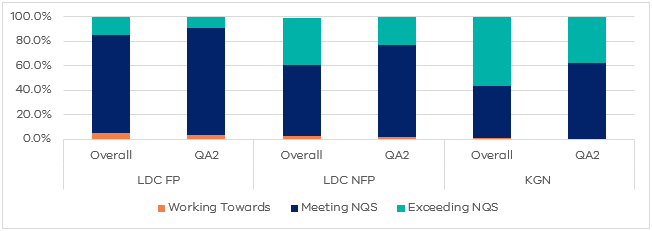

For-profit long day care services in Victoria are more likely to be rated as ‘Working Towards the National Quality Standard’ than not-for-profit long day care services, and less likely to exceed the National Quality Standard. They are also more likely to be working towards Quality Area 2 (child health and safety) and less likely to exceed Quality Area 2 than not-for-profit long day care services. There are now thousands of ECEC services in Australia run by providers with a complex array of business structures and priorities.

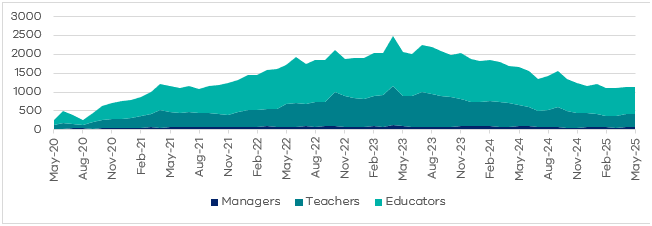

The sector faces significant workforce challenges including shortages, casualisation and the use of labour hire, and high turnover rates. In Victoria, 66.8 per cent of long day care and standalone kindergarten service staff have worked at their service for 3 or fewer years, including 22.7 per cent for less than one year. Analysis of large providers nationally by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission showed not-for-profit long day care services had a 27 per cent turnover rate, and for-profit services had a 41 per cent turnover rate.

Ultimately, the workforce is core to the delivery of high quality and safe services for children. Proper planning for workforce growth linked to a funding model that invests in quality, professional development, and proper conditions is essential.

The Commonwealth Government must lead an urgent rethink of the ECEC system. This needs to prioritise quality and safety, reconsider the current funding model and reliance on the market, plan for the workforce children need, and set a 10-year strategy to fundamentally reform the system.

A new, time-limited, Early Childhood Reform Commission should be established and tasked by the Commonwealth and state and territory governments to support the fundamental reset of the sector. The Commission should be supported by a parent advisory group, so that the people who know what children need most inform the direction of the whole system.

Removing bad actors from the system cannot wait for this longer-term work to occur. In addition to state regulatory powers, the Commonwealth Government has established new powers to stop child care subsidy funding for providers with safety or quality concerns. However, closing a service suddenly can significantly disrupt the lives of families and children who rely on it. Commonwealth and state and territory governments should establish a process in advance, to allow trusted, high-quality providers to step-in and take over a service, similar to the way an administrator can be appointed in other settings. This would maintain the continuity of a service’s operation and allow the new provider to make the necessary quality and safety improvements. Any necessary changes to the National Law to facilitate this should be made.

Recommendation 1: Safety, rights, and best interests of children Make the safety, rights, and best interests of children the paramount consideration for staff in services, managers, service providers, their owners, funders and board members. This should be done by changing the National Law. Recommendation 2: Commonwealth Government-led rethink of the ECEC system 2.1 Call for the Commonwealth Government to lead a rethink of the ECEC system. This needs to prioritise quality and safety, reconsider the current funding model and reliance on the market, and set a 10-year strategy to fundamentally reform the ECEC system, including careful planning for workforce growth and quality. 2.2 Call for the Commonwealth Government to establish a process to quickly appoint a trusted, high-quality provider to take over a service that has had its funding or other approvals cancelled, to quickly improve quality and safety, and enable continuity of access for families. This process should include consultation with the relevant state or territory government. Where necessary, the National Law should be amended to facilitate this. Recommendation 3: National Early Childhood Reform Commission Advocate for National Education Ministers to establish and resource a time-limited Early Childhood Reform Commission to provide dedicated focus and capacity to prioritise national ECEC reforms. National Education Ministers should direct the Commission’s work program and deliverables, and it should be informed by a parent advisory group. |

Part 2: Preventing predators entering the ECEC system

The best way to prevent child harm and abuse in ECEC services is to ensure unsafe and unsuitable people do not enter them in the first place.

Part 2 of the report looks at ways to prevent dangerous individuals from working in the sector.

There is no silver bullet. The Review recommends a system of checks and balances that work together to keep children safe. All parties need to play a role in this system of checks and balances.

A new National Early Childhood Worker Register (National Register) is essential. This register should include people’s employment history (so it is known to potential employers) and record if a worker has been involved in misconduct.

Recruitment practices need to be significantly improved by employers, including for casual and labour hire staff.

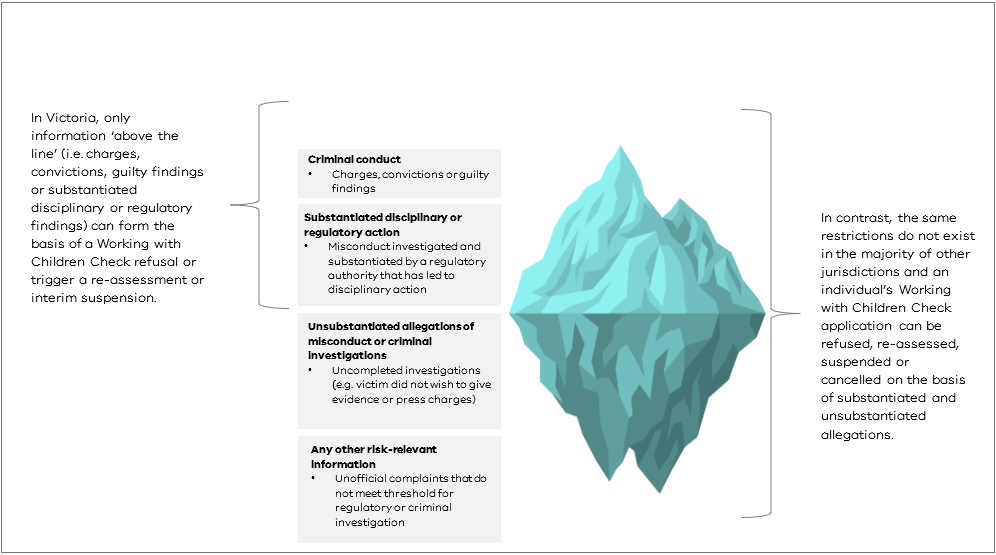

The Working with Children Check scheme needs to be overhauled so that an individual’s clearance can be suspended or refused when there are credible allegations or patterns of concerning behaviour with children. This cannot be done in isolation.

Urgent changes also need to be made to the Reportable Conduct Scheme so that information relevant to risk, whether substantiated or not, is proactively and consistently shared with the Working with Children Check screening authority to form a complete picture of risk.

This should be supported by a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability that brings together, and assesses information and intelligence, that is currently held in different places.

In Victoria currently, the Working with Children Check and Reportable Conduct schemes sit in 2 separate entities. The Review recommends that they (and the Child Safe Standards) be brought together in a single entity. The Review considers the Social Services Regulator would be an appropriate entity to consolidate those functions. Immediate steps should be taken to design and establish the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability. Together, these changes will significantly strengthen the safety net around children.

Chapter 2: Establish a new National Early Childhood Worker Register

There is currently no national register of early childhood workers, noting Victoria is establishing its own. This makes it very difficult to get an accurate picture of an individual—including their qualifications and work history, which may span across the country—and can make it difficult to make the best recruitment decisions and to trace a person’s movements if a concern or incident arises.

Victoria establishing an Early Childhood Workforce Register (Victorian Register) is a step forward. However, a national register needs to be hosted by the Commonwealth Government to protect against predatory and unsafe individuals moving between jurisdictions.

There is an urgent need to create a national register of people that shows who is banned from working in the sector—with providers compelled to look at this list before employing staff. The Review therefore recommends a National Early Childhood Worker Register to capture and verify information about ECEC educators and staff.

However, this should not simply be a static list. To be meaningful, state and territory ECEC regulators should have legislated powers to suspend and remove people from the National Register. In Victoria, consideration should be given to how the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment capability could support this decision making and avoid duplication of effort across the system (see Chapter 4).

Establishing the National Register must be a high priority for the Commonwealth Government, and legislated register powers for regulators a high National Law reform priority. However, if the Commonwealth Government does not action this, the Victorian Government should act and establish a nation-leading approach. The Victorian Register, in the meantime, needs to be designed to be consistent with the findings of this Review, and it should be built in a way that it can be compatible with a National Register at a later date.

Recommendation 4: National Early Childhood Worker Register 4.1 Accelerate a National Early Childhood Worker Register covering all early childhood education and care staff across Australia who have regular contact with children, including casual staff. The Commonwealth Government should host the Register, and access to information should be differentiated for regulators and employers. 4.2 Amend the National Law to give regulators the ability to de-register individuals based on an assessment of their suitability to work in ECEC settings. 4.3 Victoria should ensure the design of its Register is consistent with the findings of this Review, and be designed in a way that it will be compatible with a National Register. |

Chapter 3: Ensure best practice screening and recruitment

Employers also must take the steps necessary to ensure predators do not gain access to the system.

Rigorous recruitment practices are essential. No one should be able to work in an ECEC service unless their credentials have been verified, and their work history checked. This means contacting referees, including prior employers who may not have been specifically nominated by an applicant. Potential employers should consider whether there are any red flags in a person’s employment history both through reference checks, and by checking the National Early Childhood Worker Register (when in place). Both actions mean employers gain more information about a person’s qualifications, background and work history, including previous complaints or findings made against them.

Recommendation 5: Require best practice for recruitment and induction Issue an updated Statement of Expectations to the ECEC Regulator that asks it to increase its focus on approved providers’: a) recruitment of new staff, casuals and labour-hire, including undertaking background checks; child safety questions in interviews; and checking at least 2 previous employers, including when not listed as referees b) induction of staff, casuals, labour-hire and volunteers, so that staff know their responsibilities to keep children safe, staff codes of conduct, expected behaviours, and how to report or raise concerns; and c) child safe cultures, including their leadership, governance, and codes of conduct. |

Chapter 4: Overhaul the Working with Children Check and Reportable Conduct schemes in a single entity with a new risk function

Victoria’s Working with Children Check scheme should be overhauled and made the most effective in the country. These Working with Children Check changes must also be accompanied by changes to Victoria’s Reportable Conduct Scheme because these schemes operate together to provide a protective safety net for children. Currently the Working with Children Check scheme and Reportable Conduct scheme sit in 2 separate entities. The Review recommends that they (and the Child Safe Standards) be brought together in a single entity. The Social Services Regulator would be an appropriate entity to consolidate these functions.

Victoria’s Working with Children Check should not tolerate risks to children’s safety in any setting. The Working with Children Check screening authority should have the power to act swiftly and decisively if it receives information that puts children’s safety in doubt. This means making sure all information and intelligence—from police, child protection authorities and other bodies—can be rapidly shared and used to assess, immediately suspend, and ban someone from working with children.

Review of Working with Children Check decisions should also be made by a body with a specialist child safety lens, so the right decisions are made in the interests of children. Further, anyone who wants the privilege of working with children must undertake online child safety training and testing to build their knowledge and affirm their commitment to safety.

The Review also recommends urgent changes to Victoria’s Reportable Conduct Scheme. Currently, the trail of information that can identify a predator’s behaviour sits in too many different places. In practice, what this means is the repository of risk-relevant information held by the Commission for Children and Young People in the form of unsubstantiated allegations can sit unused. The Review heard repeatedly about the ‘breadcrumbs’ that can be missed by the failure to piece information together. One of the most critical changes that must happen with the Reportable Conduct Scheme is to make sure that the limitations on the Commission for Children and Young People’s ability to share unsubstantiated allegations are removed.

To support these changes to the Working with Children Check and Reportable Conduct schemes, a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability must be established. That is, information and intelligence currently held in multiple places must come together. Staff must be resourced with the necessary expertise and evidence-based tools to make sound judgements around the level of risk an individual poses to a child, and provide that information to relevant decision makers so that they can act swiftly.

In designing this new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability, there are opportunities to streamline effort, minimise overlap and ensure investigative efforts are complementary, rather than duplicative. Information sharing and decision-making in relation to a person of concern for the purposes of the Working with Children Check must be automatically shared with the ECEC Regulator and the Victorian Register and National Register (when developed).

We also know that perpetrators of abuse will often move between sectors, chasing weak points to access vulnerable people. To this end, the Victorian Government should look at how it sets up this Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability for child safety, so in time, it could support broader social services regulation, including those relating to out-of-home care, disability and aged care services, to offer the greatest protection to vulnerable Victorians.

Recommendation 6: Working with Children Checks 6.1 Change the Working with Children Check regulatory framework to: a) Allow unsubstantiated information or intelligence (for example, from police, child protection or other relevant bodies) to be obtained, shared, and considered in order to assess, refuse, temporarily suspend or revoke a Working with Children Check. b) Permit a Working with Children Check re-assessment when the screening authority is notified or becomes aware of new unsubstantiated information or intelligence. c) Require organisations to verify or validate that they have engaged a Working with Children Check clearance holder to provide accurate historical and current information of movements across different organisations. 6.2 Create an internal review process for Working with Children Check decisions and remove the ability to seek review at the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal. 6.3 All applicants must complete mandatory online child safety training and testing before being granted a Working with Children Check. 6.4 Fund the Working with Children Check screening authority so it is resourced to undertake more manual assessments and interventions under new Working with Children Check settings, noting any efficiencies delivered by the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability (see Rec 8.1). 6.5 Work with the Commonwealth Government and other states and territories to develop a national approach to the Working with Children Check laws and advocate for an improved national database that is able to support real-time monitoring of Working with Children Check holders. Recommendation 7: Change the Reportable Conduct Scheme to improve information sharing 7.1 Change the Reportable Conduct Scheme regulatory framework so there is a clear proactive power to share unsubstantiated allegations with relevant regulators and agencies, remove discretion to not share substantiated findings, and recognise a finding or investigation under another state or territory’s Reportable Conduct Scheme where the reportable allegation is also captured under the Victorian Scheme. 7.2 Fund the administration of the Reportable Conduct Scheme so that it keeps pace with demand and the number of notifications, noting any efficiencies delivered by the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability (see Rec 8.1). Recommendation 8: Establish a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability and bring child safety risk information together in one place 8.1 Invest in the design and establishment of a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability that: a) provides up-to-date information to join up the ‘breadcrumbs’, including opportunities to use new technologies such as Artificial Intelligence that can quickly scan information and flag patterns of concern b) equips assessors with fit-for-purpose risk assessment tools so they can exercise sound judgement about an individual’s suitability to work with children; and c) complements and works together with other regulatory schemes so there is a common foundation across social services, disability, and aged care to better protect vulnerable people. This new consolidated approach should deliver:

8.2 Bring together administration of the Working with Children Check and Reportable Conduct schemes in a single entity to strengthen the safety net around children. |

Part 3: Quickly identifying and excluding predators within the ECEC system

While safeguards to entering the ECEC sector will be strengthened, services and regulators will need to maintain vigilance around individuals who engage in inappropriate or unsafe behaviour with children.

No matter how hard we try to keep predators out, some will get through. The system needs to be able to spot them and act quickly.

Part 3 recommends that the ECEC Regulator be made independent from government, with contemporary risk assessment capability to reflect the growth and complexity of the ECEC system. It needs to conduct more frequent unannounced compliance visits.

ECEC services also need to make every effort to mitigate risks within their centres through best practice staffing arrangements and building designs with lines of sight.

Chapter 5: Most rigorous inspection regime in the nation

The Review has taken care not to interfere with live investigations by the ECEC Regulator or to jeopardise criminal proceedings. However, the Review was asked to highlight priorities to support regulatory activity and reform.

The current ECEC Regulator, Quality Assessment and Regulation Division, (QARD) is located within the Department of Education. While internal protocols are in place to allow QARD to operate with independence from the broader department, the risk of conflict of interest is now higher with the roll-out of department-run early learning and childcare centres. The Review is of the view that the ECEC Regulator should be made independent and significantly strengthened. Given the specialist nature of the regulatory function and the complexity of the sector, particularly at this time, the Review recommends the independent ECEC Regulator should be standalone entity.

More eyes are needed on ECEC services to catch issues at the earliest opportunity. The number of unannounced visits being made to services is not sufficient to drive vigilance and compliance. Victoria should lead the nation in compliance visits to ECEC services, with unannounced visits to all services every year.

The ECEC Regulator must also have the tools and wherewithal to tackle the much more complex regulatory environment it now faces. A Capability Review for the ECEC Regulator should be undertaken as a priority to support its work. The scale and composition of the ECEC service landscape has grown and changed since the ECEC Regulator was initially established. Regulation needs not only to catch-up to these changes but be ahead of the curve to anticipate future risks and trends. To do this, it needs risk assessment and Authorised Officers informed by the latest technology, evidence about child safety, and the tools needed to regulate large, complex for-profit providers. Penalties need to increase to match the seriousness of breaches and also be significant for providers with bigger balance sheets.

The Commonwealth Government must play its part in this. When the National Quality Framework was first introduced, regulation of ECEC services was a shared endeavour between the Commonwealth Government and state and territory governments. The Commonwealth Government stopped contributing funding in 2018. In the final year of the National Quality Agenda National Partnership Agreement (2017–18), the payments to states and territories were $20.33 million. This represented just 0.22 per cent of the $8.9 billion the Commonwealth Government spent on child care services that year. Since then, the scale and complexity of the system has grown significantly, rising to $14.15 billion Commonwealth Government expenditure in 2023-24. The Review recommends Commonwealth Government funding for state and territory regulators is reinstated.

Recommendation 9: An independent ECEC Regulator The ECEC Regulator should be made independent of the Department of Education, to avoid conflicts of interest, and should be strengthened to regulate an increasingly complex ECEC system. Recommendation 10: Most rigorous inspection regime in the country The ECEC Regulator should conduct more visits to services each year, to: a) increase the volume and frequency of unannounced compliance visits to a nation-leading standard of at least once per service every 12 months; and b) reduce the average time between Assessment and Rating visits. Recommendation 11: Capability Review and modern risk assessment for a complex and growing sector 11.1 A Capability Review for the ECEC Regulator should be initiated as a priority. This should support the ECEC Regulator to modernise its risk assessment framework, tools, and training for Authorised Officers to: address complex for-profit approved providers, associated entities and corporate relationships; improve consistency of Authorised Officer’s assessments; incorporate contemporary evidence on child sexual offending; regulate individual employees under the proposed National Register powers; and better utilise technology in assessing risk, including exploring safe use of Artificial Intelligence. 11.2 Call for the Commonwealth to commission the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission to investigate ways to address the complex legal structures and arrangements being used in the ECEC sector, so Regulatory Authorities have the information, tools, and powers to effectively regulate approved providers and the ‘fit and proper person test’ in the National Law. Recommendation 12: Increase penalties for offences Call for a material increase to the maximum penalty amounts for offences under the National Law to better align penalties with the seriousness of offences. Recommendation 13: Funding for effective regulation 13.1 The ECEC Regulator should be appropriately funded to deliver its functions, including for the recommendations of this Review, and to make sure funding is in-line with the number of services to be regulated. 13.2 Call for the Commonwealth to reinstate funding for state and territory ECEC regulators and increase it to recognise the significant growth in the ECEC system. Funding should enable Victoria to meet its obligations in national arrangements, including as host jurisdiction of the National Law for early childhood education and care. |

Chapter 6: Improve the centre environment

Adults having eyes on each other protects children and protects the majority of educators and other staff who are doing the right thing. Improvements can be made to the centre environment to support this.

At least 2 adults should be in the presence of a child in ECEC services, wherever possible. To support this, changes are needed within ECEC services to improve lines of sight and limit the opportunities for an adult to be alone with children. Staffing arrangements should be reviewed, including consideration of key educator to child ratios and the practice of 2 adults being visible to each other when with children (known as the ‘four eyes on the child’ principle).

The Review also has concerns that under the National Law there is no general limit on the number or proportion of staff that can be ‘actively working towards’ their qualifications in any one service. While this measure was designed to enable people to get valuable work experience, it can be misused by services to put cheaper, and less experienced staffing arrangements in place. Tightening the use of these arrangements should be part of the review of staffing arrangements.

A national trial of Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) in centres should also take place to evaluate its use as a regulatory and investigative tool—but with care taken to listen to the concerns of parents, services, and staff. The Review also notes that the Victorian Government is implementing a ban on personal devices in ECEC settings in September 2025.

Recommendation 14: Improve staffing arrangements in services Call for a national review of staffing arrangements in early childhood education and care centres, including consideration of: a ‘four eyes’ rule of 2 adults visible to each other while with children; removing or amending the ‘roofline’ rule; and tightening rules permitting ‘working towards qualification’ staff so that there are more qualified eyes on children at any one time. Recommendation 15: Improve lines of sight in ECEC centres Call for the Commonwealth Government to fund a Child Safe Buildings Grants Program for fixtures and fittings or minor construction works that address physical barriers to clear lines of sight in existing ECEC centres. This should be funded by the Commonwealth Government but could be delivered through the state and territory jurisdictions. Service and building owners should make a co-contribution, based on their level of financial resources. Recommendation 16: Trial the use of Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) Call for a national trial of CCTV in early childhood education and care settings that focuses on its use as a regulatory and investigative tool. The trial should address data security and access concerns and gauge the views of regulators, providers, staff and families. The trial should also address any current barriers to regulators accessing existing CCTV evidence for investigations. |

Chapter 7: Strengthen transparency and parents’ right to know

Parents will often be the first ones to notice that something may be wrong for their child. When parents and educators work together in partnership and have the right information, they can and will act decisively to identify risks, raise concerns, and protect children.

Parents need clear and transparent information about early childhood education and care services’ quality and compliance so that they can provide additional eyes and raise the alarm when things are amiss. However, parents don’t always have the information they need to make informed decisions. All information about service quality ratings and non-compliance must be shared openly, quickly, and accessibly with parents and the broader community. This information should be made available in a variety of commonly used languages to be accessible to families for whom English may be a second language.

The Review heard that many parents don’t feel confident in identifying signs of abuse or grooming and can hesitate to raise concerns. Parents should be supported with evidence-based guidance to empower them to identify and act on safety concerns.

Open and timely conversations between parents and services are more likely to happen when processes for responding to complaints and concerns are clear and transparent. When an investigation occurs, parents need to be confident the matter will be handled in an appropriate manner, and that everything is being done to keep their children safe.

Recommendation 17: Make accessing information about service quality ratings easier for parents 17.1 Call for the Commonwealth Government to improve information for parents about service quality and compliance on the Starting Blocks website, including: clear information on the National Quality Standard and which of the sub-elements are being met or not; details of service and provider ownership; and compliance history of services. 17.2 Call for the National Law to require services to display on their website, and inform families of, their quality ratings and any enforcement actions against them, prior to enrolment, when ratings change, and when new enforcement actions are imposed. 17.3 The ECEC Regulator should issue a modified ratings certificate which includes the period of time that a service has been rated as ‘Working Towards’ that must be prominently displayed in a service’s reception area and on its website. 17.4 The ECEC Regulator should more regularly publish the full scope of permitted compliance and enforcement activity information on its website. Recommendation 18: Support parents to raise and report concerns 18.2 Update and promote advice for parents on how to make complaints or raise concerns with their early childhood education and care service, and the ECEC Regulator, including via the public complaints and enquiry hotline. |

Chapter 8: Support the workforce

The ECEC workforce is our greatest asset when it comes to educating and protecting children. The ECEC workforce is overwhelmingly made up of committed, capable professionals. We should be supporting and investing in them, their professional development, and their careers. Educators and other staff in ECEC services need to be trained to confidently identify and act on any signs of abuse or harm and be encouraged to speak up for safety.

The ECEC system needs to give the workforce time and space to train, develop and pursue best practice in their services.

Investing in our ECEC professionals will help make a career in early education more attractive and sustainable, so we have experienced people in ECEC centres. In the meantime, action is needed to crack down on poor quality Registered Training Organisations which deliver sub-par ECEC qualifications. Educators deserve access to a quality education themselves—with courses that recognise the importance and complexity of the work, promote best practice and are grounded in children’s rights and safety. This will ensure all educators are skilled and capable.

Beyond initial qualifications, child safety training must be mandatory for all people involved in ECEC services throughout their careers—from the educators on the floor, to the cooks in the kitchen, through to the managers and board directors of services. The Commonwealth Government’s child care subsidy only funds services when parents pay the fee for their children to attend. This means that to have a dedicated professional development day with staff, services need to charge parents fees for the day they are closed, or not have any revenue that day. The Commonwealth Government should fund long day care services to release staff for training, which will strengthen their skills and knowledge on child safety.

The Commonwealth Government should invest in quality improvement programs for services in long day care, akin to the Kindergarten Quality Improvement Program established by Victoria. The program should support service leaders and educators to improve their governance and educational programs. The Commonwealth Government should consider rolling this program out to other service types, such as family day care and outside school hours care.

Staff working within ECEC services are best placed to report suspected misconduct or child safety risks in their workplace. However, educators and workers are met with a confusing range of places to report when they have a child safety concern. Another barrier can be workplace cultures that discourage feedback and complaints and make staff fearful of reprisal for making reports. Staff need to feel safe to raise concerns and be given the tools and confidence to speak-up and step-in

Recommendation 19: Stronger action on poor quality training courses Call for Commonwealth Government action to improve ECEC training and placements, including stronger Australian Skills Quality Authority powers to address poor quality registered training organisations, including those who are also ECEC service providers. This should focus on training outcomes that better prepare students for working in an ECEC setting, including child safety knowledge and skills. Recommendation 20: Mandatory child safety training 20.1 Accelerate national mandatory child safety training for all people involved in the provision of ECEC through a change to the National Law. This should include people who may not directly work with children, such as Approved Providers, board members and office holders, management and administrative or non-educator staff, with tailoring based on role and contact with children. The approach should be national, but with local training tailored to capture specific state and territory laws, such as Victoria’s legislated Child Safe Standards and Reportable Conduct Scheme. 20.2 Call for the Commonwealth Government to fund time release for staff to undertake relevant training. This could be done by direct funding allocation or by changing Commonwealth Government child care subsidy rules to fund services to provide training to staff on child safety. 20.3 To complement any national mandatory training, the Department of Education should update its existing ‘PROTECT’ training on identifying and reporting concerns and provide training on child sexual abuse prevention education for educators, including how to teach children about body safety, consent, and social and emotional learning, including seeking help. Recommendation 21: Professional support program on quality, child safety and safeguarding 21.1 The Department of Education should partner with Early Childhood Australia to expand its Children’s Safety and Safeguarding in Early Childhood Settings professional support program of webinars and resources. This program should provide service leaders and staff with the latest evidence and best practice on child safety and safeguarding and cover how to build a child safe culture, recruit, train and supervise a child safe workforce, and respond to risks. 21.2 Call for the Commonwealth Government to fund a Child Care Quality Improvement Program for child care subsidy-approved services, similar to the Victorian Kindergarten Quality Improvement Program. Recommendation 22: Give ECEC workers the confidence to raise concerns Provide training and clear guidance on how ECEC staff can report concerns, allegations and complaints, as part of a ‘speak-up’ culture. This should include how to anonymously report to regulators if staff do not feel supported to speak-up in their service. |

Conclusion and next steps

The Victorian Government commissioned a rapid review, and its recommendations warrant a rapid response.

The Victorian Government should share this Review at the earliest opportunity with the Commonwealth Government and other jurisdictions, recognising the need for greater national collaboration and consistency. National Education Ministers are due to meet on 22 August 2025, which would provide a timely opportunity to start coordinated action on these important recommendations.

Recommendations that are directed at the Commonwealth Government or that require changes to the National Law are set out in Figure 1 below, and should be raised at the Education Ministers Meeting. This includes expediting a National Register and legislative power to remove individuals from it, and making the safety, rights and best interests of the child the paramount consideration in law.

Key matters in this Review require the urgent attention of the Victorian Government. Most importantly the Victorian Government should focus on putting in place additional checks and steps that prevent predators working in the system. These actions will make a profound change in the system.

This will require overhauling the Working with Children Check scheme and addressing gaps in the Reportable Conduct Scheme as a matter of priority. These schemes should be brought together in a single entity. Immediate steps should be taken to design and establish the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability.

These changes should not be made in isolation but need to be seen as part of the strengthened child safety regime described in this Review. This work is complex, and consideration should be given to how it can be phased.

Work to make the ECEC Regulator independent should commence immediately and be in place within 12 months, supported by a Capability Review that will guide the skills, functions and powers needed to be a cutting-edge regulator of an increasingly complex market of providers. This should happen alongside the recruitment of additional Authorised Officers and the development of modern risk assessment tools.

In parallel, the focus of all tiers of government needs to be on the broader re-think of the ECEC system and development of an overarching strategy to fundamentally reform the system.

| For the Victorian Government | Rec |

| Require ECEC employers to have best practice for recruitment and induction | 5 |

| Working with Children Checks overhaul | 6.1–6.4 |

| Change the Reportable Conduct Scheme to improve information sharing | 7 |

| Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability | 8 |

| An independent ECEC Regulator | 9 |

| Most rigorous inspection regime in the country | 10 |

| Capability review and modern risk assessment for a complex and growing sector | 11.1 |

| Funding for effective regulation | 13.1 |

| Modify ratings certificates and publish enforcement activity more regularly | 17.3–17.4 |

| Support parents to raise and report concerns | 18 |

| Mandatory child safety training – attuned to evidence on risks and prevention | 20.3 |

| Professional support program on quality, child safety and safeguarding | 21.1 |

| Give workers the confidence to raise concerns | 22 |

| For the Commonwealth Government | Rec |

| Capability review and modern risk assessment for a complex and growing sector | 11.2 |

| Funding for effective regulation | 13.2 |

| Improve lines of sight in ECEC centres | 15 |

| Make accessing information about service quality ratings easier for parents | 17.1 |

| Stronger action on poor quality training courses | 19 |

| Mandatory child safety training – funded time release | 20.2 |

| Fund a Child Care Quality Improvement program | 21.2 |

| For National Reforms and National Law changes | Rec |

| Safety, rights and best interests of children | 1 |

| Commonwealth Government-led rethink of the ECEC system | 2 |

| National Early Childhood Reform Commission | 3 |

| National Early Childhood Worker Register | 4 |

| National approach to Working with Children checks | 6.5 |

| Increase penalties for offences | 12 |

| Improve staffing arrangements in services | 14 |

| Trial the use of Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) | 16 |

| Make accessing information about service quality ratings easier for parents | 17.2 |

| Mandatory child safety training – National Law | 20.1 |

| For the Victorian Government | Rec | Immediate, within 3 months | Within 12 months | 12+ months |

| Require ECEC employers to have best practice for recruitment and induction | 5 | New Statement of Expectations | ||

| Working with Children Checks overhaul | 6.1–6.4 | Start design and draft legislation | New legislation, changes implemented | |

| Change the Reportable Conduct Scheme to improve information sharing | 7 | Start design and draft legislation | New legislation, changes implemented | |

| Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability | 8 | Start design and draft legislation | Functions consolidated | |

| An independent ECEC Regulator | 9 | Design and draft legislation | Independent Regulator established | |

| Most rigorous inspection regime in the country | 10 | Start recruiting Authorised Officers | More services receive annual visit | All services receive annual visit |

| Capability review and modern risk assessment for a complex and growing sector | 11.1 | Design and consult with experts | New framework in place | |

| Funding for effective regulation | 13.1 | Immediate funding package | ||

| Modify ratings certificates and publish enforcement activity more regularly | 17.3–17.4 | Increase frequency of publishing | ||

| Support parents to raise and report concerns | 18 | Consult with experts and parents | Release updated guidance | |

| Mandatory child safety training—attuned to evidence on risks and prevention | 20.3 | Consult with experts and workforce | Release updated guidance | |

| Professional support program on quality, child safety and safeguarding | 21.1 | Partner with Early Childhood Australia, expand program | ||

| Give workers the confidence to raise concerns | 22 | Consult and publish guidance | ||

| For the Commonwealth Government | Rec | |||

| Capability review and modern risk assessment for a complex and growing sector | 11.2 | Task ACECQA and ASIC | ||

| Funding for effective regulation | 13.2 | Negotiate new National Agreement | Funding provided to state / territories | |

| Improve lines of sight in centres | 15 | Design with all jurisdictions | Commence grants program | |

| Make accessing information about service quality ratings easier for parents | 17.1 | Consult with experts and parents | Updated Starting Blocks website | |

| Stronger action on poor quality training courses | 19 | Task ASQA to address

| ||

| Mandatory child safety training – funded time release | 20.2 | Design with all jurisdictions | Commence program | |

| Fund a Child Care Quality Improvement program | 21.2 | Design with all jurisdictions | Commence program | |

| For National Reforms and National Law changes | Rec | |||

| Safety, rights and best interests of children | 1 | Start design and draft legislation | New National Law legislation | |

| Commonwealth Government-led rethink of the ECEC system | 2 | Start design and consultation | Develop long term plan | New 10-year strategy for ECEC |

| National Early Childhood Reform Commission | 3 | Start design and consultation | Commission established | |

| National Early Childhood Worker Register | 4 | Start design and draft legislation | National Register established | |

| National approach to Working with Children Checks | 6.5 | Start design and consultation | Agree approach | Implement approach |

| Increase penalties for offences | 12 | Start design and draft legislation | New National Law legislation | |

| Improve staffing arrangements in services | 14 | Explore package of staffing changes | Start design and draft any legislation | Any new changes implemented |

| Trial the use of Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) | 16 | Commence design and consultation | Commence trial | Evaluate trial and set next steps |

| Make accessing information about service quality ratings easier for parents | 17.2 | Start design and draft legislation | New National Law legislation | |

| Mandatory child safety training – National Law | 20.1 | Design and draft legislation | New National Law legislation |

Part 1: Governments to take greater responsibility for running the ECEC system

Part 1, Chapter 1 calls for governments to take greater responsibility and rethink the national early childhood education and care system.

Chapter 1: Rethink the national ECEC system

Chapter 1: Rethink the national ECEC system

This chapter recommends making the safety, rights and best interests of children the paramount consideration for decision making in ECEC services and a fundamental rethink of the system by governments.

1.1 Child safety needs to underpin the ECEC system

The safety, rights and best interests of children must underpin all decision making in the ECEC system, from staff on the floor in centres right up to the boardrooms of service providers.

Article 3 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child requires the best interests of the child to be a primary consideration in all actions concerning children undertaken by public or private social welfare organisations. Under the ECEC system’s National Law, the rights and best interests of the child is one of 6 ‘guiding principles of the National Quality Framework’. However, it does not stipulate how this principle must be applied.

While it is clear to the Review that the majority of services across the system care deeply about the children in their care and prioritise their safety, there are tensions in the system that lead some providers to prioritise other things, including profit in some instances. The current mix of legislative and regulatory obligations for providers can create potential conflicts between the best interests of children and other duties.

The Review heard that the rapid expansion of the sector has created perverse incentives for shortcuts in education and training and that some for-profit providers may feel pressure to maximise value to shareholders.

Current legal frameworks are often interpreted as prioritising procedural fairness for employees, which can act as a brake on employers taking early or decisive action to protect children, for fear of industrial or legal challenges. Privacy laws can be seen as a barrier to proactive information sharing relating to individuals of concern. All these factors can divert focus from what is truly in the best interests of children.

These broader concerns filter down and inform decisions within services and can stifle reporting and important information being passed on to those who need it. Queensland’s Review of System Responses to Child Sexual Abuse reported that fear of reputational risks, or defamation and other legal risks to both organisations and individual staff may deter staff from raising concerns about a person and sharing that information with those who need to know, particularly where allegations have not been substantiated.

The Wheeler Review in New South Wales recognised these challenges in ECEC services, saying:

In addressing any competing interests, providers and services must ensure that the interests of enrolled children are of paramount importance in all decisions and transactions. Providers and services must place their duty to enrolled children ahead of those owed to their shareholders and other stakeholders.

Making the safety, rights, and best interests of children a ‘paramount consideration’ in the National Law is needed to unequivocally place children’s needs and interests above all other considerations. As Anne Hollonds, the National Children’s Commissioner, has said:

‘Everyone involved needs to make child safety their number one priority,

from the boardroom to the sandpit.’

This paramount consideration obligation should apply to staff in services; responsible persons; persons with management or control; approved providers of services; and entities that own and fund approved providers of services, including board members.

The amendments to the National Law should consider inconsistencies with Commonwealth and state/territory laws; establishing the necessary architecture to include actors other than providers and services, such as directors and office holders, and employees; and enforcement powers and options.

Detail of how to interpret the concepts of the safety, rights and best interests of children as a paramount consideration should be included in the Regulations and through operational guidance. This should consider how to minimise risks of differing and conflicting interpretations and the risk of unintended consequences in application, such as discrimination or unreasonable expectations placed on employees. Current frameworks for workplace occupational health and safety requirements may provide a useful model. These make clear that occupational health and safety is everyone’s business, duties and responsibilities apply to all levels of organisations, they are outcomes-based and build a shared understanding and culture of safety and risk management. They are usually accompanied by clear policy, guidance and training to operationalise.

Governments should produce guidance to make it clear how this paramount consideration should operate in practice for different decision makers—from senior managers in head office through to educators in the room—and how to manage conflicts of interest. Given this would be a change to the National Law, the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority could produce this guidance, as it has for the recent National Quality Framework Child Safe Culture Guide.

Recommendation 1: Safety, rights and best interests of children Make the safety, rights, and best interests of children the paramount consideration for staff in services, managers, service providers, their owners, funders and board members. This should be done by changing the National Law. |

1.2 The system needs fundamental change

The ECEC system has grown rapidly to meet the community need for early childhood education and care.

Since 2015 in Victoria, the number of long day care services has grown from 1,280 to 2,049—a 60 per cent increase. Over the same time, there has been a small increase in standalone kindergarten services, growing from 1,197 to 1,236 (3.3 per cent). Of the 769 new long day care services in Victoria since 2015, 726 (94 per cent) are operated by for-profit providers. For-profit long day care services in Victoria are more likely to be ‘Working Towards’ the National Quality Standard than not-for-profit long day care services, and less likely to exceed the National Quality Standard. An overview of the ECEC system in Victoria, including more data and trends over time, is at Appendix 2.

This rapid growth has not been accompanied by a coherent plan to ensure the delivery of safe and quality services. Rather, the market has been left to respond to financial incentives that encourage providers to open services and charge high fees, but does not drive investment in quality or safety, or a stable, capable and professional workforce. It means that the funding a service receives is linked to the fees charged to parents, not the needs of the children or the cost of delivery of high-quality education and care. It allows providers to charge premium fees for a minimum standard service, and in some cases maximise profits from the system. The child care subsidy represents a large amount of taxpayer’s money and needs much tighter controls on how it is spent.

It may have once been that a market-driven approach was appropriate for the ECEC system—when the sector’s composition was different, and when workforce challenges were not so significant —but this is no longer the case. It is clear now that this system is not delivering the outcomes government wants, or the community expects.

Governments need to monitor and understand how the system is changing, including who is entering or leaving the sector. They need to reconsider how they fund, monitor, support and regulate the system. The market has been allowed to run too far, for too long.

Australia’s ECEC system needs a fundamental reset.

1.2.1 Governments need to take responsibility for running the ECEC system

Governments need to use their levers and adapt their settings to protect children and families and get the outcomes sought from the system, including educational outcomes for children.

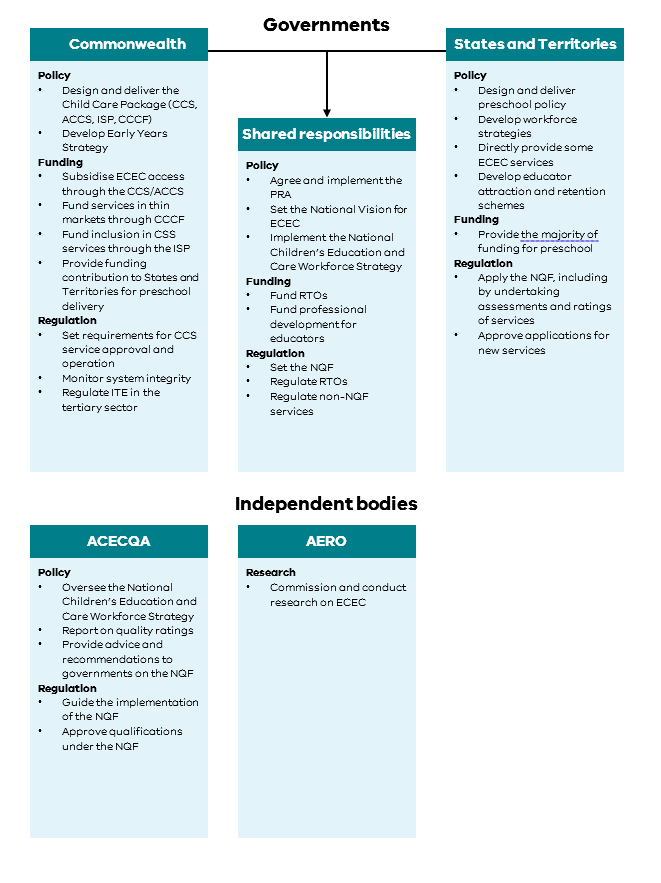

Current roles and responsibilities for the ECEC system is split across Commonwealth, state and territory, and local governments. They have evolved from a historical split of responsibilities where the state or territory is responsible for ‘education’ and the Commonwealth Government for ‘care’ to support workforce participation. This split doesn’t match the daily experience of children and families. Children are always learning, even when in ‘care’, and many children receive the dedicated ‘educational’ program (kindergarten) in a long day care service. Despite the aspirations of a single National Quality Framework, the split continues to drive governments’ approach to the system.

The Commonwealth Government is the majority funder of child care for children aged from 0–5, but states and territories are the majority funder of kindergarten for 4-year-olds (and 3-year-olds, where offered). States and territories are responsible for regulating all services in the sector, but the largest portion of services they regulate are long day care services driven by Commonwealth Government funding.

This leads to gaps in the system.

The workforce is the main way to deliver quality and safe services for children, but no government is specifically or holistically responsible for the workforce, and the ECEC sector and workforce continues to experience many challenges.

A lack of dedicated and coordinated effort, funding settings and the funding approach have contributed to workforce challenges including shortages, casualisation, the use of labour hire staff, and high turn-over rates.

In Victoria, 66.8 per cent of long day care and kindergarten service staff have 3 or fewer years at their service, including 22.7 per cent who have less than one year. Analysis of large providers nationally by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission showed not-for-profit long day care services had a 27 per cent turnover rate, and for-profits had a 41 per cent turnover rate. Further context on the ECEC workforce is in Appendix 2.

No single factor is determinative of child safety, but there are many influencing factors. A workforce that is highly casualised may be less likely to feel comfortable to speak-up and report something if they have concerns. A workforce that is low paid and not properly valued by the community may struggle to attract and retain the most capable people. A workforce that struggles to attract staff may lead to services having to choose between hiring staff they don’t have full confidence in, or reducing capacity and turning children away. A workforce where many are less experienced, or are still working towards their qualification, may not know what to look for to protect and promote child safety, or how to report concerns. A workforce that has high turnover makes it hard to build a strong culture within a service, or strong relationships with children. A workforce where one staff member undertaking professional development ‘off the floor’ creates rostering and operational challenges is not one where professional development will always be prioritised.

Governments must work together to clarify and resolve their responsibilities in ECEC, ensuring that gaps are filled and ambiguities resolved. This should then be formalised, for example, in a broad intergovernmental agreement that addresses the whole ECEC system, and any funding implications addressed through a National Agreement.

1.2.2 The system needs a long-term vision and a plan to achieve it

The Commonwealth Government should lead work with all levels of governments to clearly articulate Australia’s vision for the ECEC system. This should include moving from a split approach to ‘education’ and ‘care’ to a strong, system-wide focus on the safety, wellbeing, education and development of every child, in every setting. This will clarify for governments what they are using their levers to achieve and send a clear message to the sector and the community about where the system is heading. Governments started developing a National Vision for Early Childhood Education and Care in Australia, but this has stalled. It should be restarted.

Governments should then develop a long-term plan to meet their objectives. This should outline how they will move ECEC from a market-driven model to a system that is actively managed with greater emphasis on quality and safety for children. This could include:

- reform to the funding system, or a new funding system, to better align incentives, ensure value for money for governments, and limit the ability of providers to unreasonably profit from public funds

- sustained and coordinated investment in the pay and conditions for the workforce and future workforce planning

- tighter regulation of providers, including being more willing to use funding and regulatory levers to remove low quality or poor performing providers from the system

- consideration of the optimal market composition and balance of providers in the sector, and how this can be achieved

- investment and support for high-quality providers to expand, especially not-for-profit providers who may need additional help

- investment in incentives and support for quality improvement

- monitoring the level of profit being generated from public funding

- greater coordination and planning of provision, and planning for service transition when providers fail or have funding or approvals withdrawn; and

- equity and inclusion of children from different socio-economic backgrounds, cultures or those with disability or developmental delay.

While a long-term plan is important to addressing systemic issues in the ECEC system, some actions cannot and need not wait. Elsewhere in this report, the Review has recommended the Commonwealth Government commence a quality improvement program in long day care services, resume investing in the regulatory system, change funding rules to better support staff professional development, and fund grants to improve lines of sight in services. All these actions can commence almost immediately and, in the context of a long-term reform program, are ‘no regrets’ investments that will be of benefit irrespective of how governments eventually progress long-term reform.

Commonwealth legislation to give greater powers to stop or add conditions to child care subsidy funding for poor quality or unsafe services is welcome and should be applied. It is important for governments to effectively enforce a quality floor, remove ‘bad eggs’ from the system, and send a strong signal to others to maintain or improve quality and safety. However, ceasing funding will typically mean closing a service, which can disrupt families’ lives. In some cases, there may be other services nearby with places available, but in others it may be both possible and beneficial to keep a service open by bringing in a different, high-quality provider to address quality and safety concerns and maintain service continuity for families.

Governments should have a clear plan and mechanism to deal with service closures, including by facilitating another provider to take over the operation of a service, with a focus on quality. When ABC Learning collapsed, Goodstart was established to take over most of its operations.

However, this process took over a year to complete. Having a process developed in advance would make it easier and quicker for other providers, including not-for-profits and government providers, to quickly step-in and operate the service. This planning should involve state and territory governments, as they are more likely to know local communities and know which local providers would be strong candidates to take over a service.

Changes may also be needed to the National Law to facilitate this in a timely way, and the new provider may need financial or other supports from government to quickly improve the quality and safety of the service. But the Review considers that it may, in some circumstances, be a good way to address what can be competing objectives of maintaining safety and quality and maintaining access for families. It could also provide an opportunity for government to support high-quality providers to grow their operations.

Recommendation 2: Commonwealth Government-led rethink of the ECEC system 2.1 Call for the Commonwealth Government to lead a rethink of the ECEC system. This needs to prioritise quality and safety, reconsider the current funding model and reliance on the market, and set a 10-year strategy to fundamentally reform the ECEC system, including careful planning for workforce growth and quality. 2.2 Call for the Commonwealth Government to establish a process to quickly appoint a trusted, high-quality provider to take over a service that has had its funding or other approvals cancelled, to quickly improve quality and safety and enable continuity of access for families. This process should include consultation with the relevant state or territory government. Where necessary, the National Law should be amended to facilitate this. |

1.2.3 Establish a commission to drive national reform

The Education Ministers Meeting (which consists of Commonwealth, state and territory Education Ministers, across ECEC, schools and higher education) provides a forum for collaboration and decision-making on ECEC. However, in light of recent child safety incidents, several Commonwealth and state ministers have expressed frustration with the slow pace of national reforms in ECEC.

Many Education Ministers have responsibility for school education or other portfolios in addition to ECEC, and departmental officials often have broad responsibilities, including the ongoing operation of existing programs and services, and the regulatory system.

The Review is concerned that the lack of progress in reforming the ECEC system is, in part, a result of this lack of dedicated focus on the issue. A catalyst is required to drive reform.

The Review therefore recommends the establishment of an Early Childhood Reform Commission, to accelerate national reform. While there are national frameworks in place for ECEC regulation and policy reform, they have not been as nimble as needed to respond to such a rapidly changing environment as the ECEC system has become. What is required is a Commission focused on ensuring that necessary reforms at the national level are progressed in a timely way.

The Commission would not replace ministers, officials or departments’ decision making or other responsibilities, but it would provide a specialist resource, dedicated to supporting ministers develop and progress national reforms.

The Commission could be time-limited to drive through agreed reforms, acting as an ‘honest broker’ between governments, and helping ministers to track that work is being done across the various parts of government involved.

The Commission would be solely focussed on the reform of the ECEC system, and not have its attention diverted by running grants, programs or services, or administering a regulatory system. The Commission would work with other bodies in the space, including the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority, to help ensure that agreed reform measures are implemented. The Commission should use evidence to underpin its work, and drive linkage of national, state and territory data to inform decision making by ministers.

The Commission would work to, and at the direction of, the Education Ministers Meeting. Through this model all governments would have a say in the Commission’s governance and workplan. Similar approaches are used for organisations such as the Australian Education Research Organisation and Education Services Australia.

The Commission should be established quickly and with simple governance (rather than a large board), as is appropriate for the proposed role of the organisation, working to deliver a work plan set by the Education Ministers Meeting.

The Commission should be supported by a parent advisory group to ensure that parents inform the policy that drives the whole system.

While not setting a sunset date, the Review expects that the Commission would be time limited and, if successful, cease operating in its current form within 5 years.

Recommendation 3: National Early Childhood Reform Commission Advocate for National Education Ministers to establish and resource a time-limited Early Childhood Reform Commission to provide dedicated focus and capacity to prioritise national ECEC reforms. National Education Ministers should direct the Commission’s work program and deliverables, and it should be informed by a parent advisory group. |

Part 2: Preventing predators entering the ECEC system

Part 2 looks at the various ways the ECEC system can make sure predators do not enter the ECEC system.

- Chapter 2 recommends establishing a new National Worker Register.

- Chapter 3 recommends ways to ensure best practice screening and recruitment of workers.

- Chapter 4 recommends overhauling the Working with Children Check and Reportable Conduct schemes in a single entity with a new risk function.

Chapter 2: Establish a new National Early Childhood Worker Register

Chapter 2: Establish a new National Early Childhood Worker Register

This chapter recommends establishment of a National Early Childhood Worker Register and legislative powers for regulators to remove unsuitable people from the register. It also recommends that the Victorian Early Childhood Workforce Register that is being developed takes account of this Review’s findings and is built to be compatible with the National Register.

2.1 Establishing a National Register of early childhood education and care workers

The Review heard repeatedly from service leaders, approved providers, and peak bodies that it is difficult for employers and regulators to get an accurate picture of a person’s credentials and work history. The onus is on each individual employer to assess and verify a person’s qualifications and prior employment, which often hinges on individuals being honest. While most educators do the right thing, the absence of a register creates opportunities for bad actors to abuse the system, by lying about their work experience or omitting information about past complaints, investigations or terminations. It can also make it difficult for authorities to identify which centres or families may be affected when an alleged perpetrator is charged.

In Victoria, 17.1 per cent of ECEC workers have a bachelor degree or higher qualification in a teaching field. Many of these workers are likely registered with the Victorian Institute of Teaching. These registered ECEC teachers are subject to a rigorous registration process with ongoing obligations to prove their continued suitability to teach and maintain a minimum standard of practice and learning requirements.

For the remaining more than 80 per cent of ECEC workers with regular contact with children in a service, the Working with Children Check system is relied upon as a screening tool to clear them for child-related work in the sector. Unlike Victorian Institute of Teaching registration, a Working with Children Check does not confirm the qualifications or suitability of a person to work with children (Working with Children Check is discussed in more detail at Chapter 4).

The Review heard strong support for an early childhood education and care workers register. Victoria is already taking the first steps to create a register, launching the Early Childhood Workforce Register (Victorian Register) in August 2025. It will be implemented through a phased program of work to capture information about employees at a service who have regular contact with children. The Review understands the first phase of the Victorian Register captures service employees and that the next phase (due to be delivered later in 2025) will capture agency staff. Noting the high number of casuals in the sector, this is an important next step. The Victorian Register also needs to adapt to the findings from this Review, including to make sure it has the fields necessary to capture employee histories and any disciplinary actions or investigations, alongside being built to be compatible with the national register.

Stakeholders overwhelmingly told the Review that a national register should be the priority, to avoid unsafe and unsuitable workers avoiding detection and scrutiny by moving between jurisdictions, and to make it easier for both employers and parents to access basic information about an individual working in a service.

2.2 Legislative powers to remove people from the register

Establishing a register alone will not address a person’s suitability to work in the ECEC sector, or whether they should be removed. The Review heard strong support for a regulatory authority to have the ability to suspend or remove a person from the Register. Like the Register, stakeholders overwhelmingly called for a nationally consistent approach. This would need changes to the National Law to allow state and territory ECEC regulators to perform this function in a consistent way.

Stakeholders supported a national register and legislative powers, because it would:

- create a single source of truth, allowing authorised regulators and employers to access essential background and relevant risk information (including about historical and current substantiated and unsubstantiated child safety data) about any educator or worker

- offer searchable information for employers and families to confirm the eligibility of applicants to work in the sector (by verifying a person has relevant qualifications and training and has not been struck off the register)

- facilitate the sharing of child safety risks between jurisdictions to facilitate a more complete picture of concerning patterns of behaviour and early identification of risks by reducing the need for time-consuming manual processes for employers and regulatory authorities.

Admission to the National Register should, at a minimum, require:

- a Working with Children Check (or equivalent)

- necessary minimum qualifications (where applicable), or reflect if a person is working towards a qualification, or a trainee or student; and

- completion of mandatory child safety training.

The National Register should include fields covering:

- personal details (full name, date of birth, contact)

- employment history (start date, cease date)

- if the person is currently subject to any complaints, workplace investigations or disciplinary proceedings (and the nature of these)

- if the person is excluded (by a prescribed relevant state or territory regulatory authority) from working in the ECEC sector, or if any conditions have been imposed on the individual; and

- the minimum admission requirements outlined above.

Access to information on the National Early Childhood Worker Register could be differentiated between employers and regulators, recognising the different levels of information needed for each audience.

People who are found to be unsafe or unsuitable to work in the sector should be removed from the National Register without delay, and the relevant regulator should have powers to receive a broad range of information and act on it. In Victoria, consideration should be given to how the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment capability could support this decision making and avoid duplication of effort across the system.