This chapter outlines major reforms to the Working with Children Check, an improved Reportable Conduct Scheme and the establishment of a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability. Currently the Working with Children Check and Reportable Conduct schemes sit in 2 separate entities. The Review recommends that they be brought together (along with the Child Safe Standards) into a single entity with a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability. Together, these changes will significantly strengthen the safety net around children.

4.1 Limitations of Victoria’s Working with Children Check legislative framework

The Worker Screening Act 2020 (Vic) requires that anyone undertaking child-related work in Victoria (including ECEC professionals) must have a valid Working with Children Check unless an exemption applies.

However, Victoria’s Working with Children Check laws are not fit-for-purpose and must be rebalanced in favour of child safety.

Compared to other states and territories, Victoria’s Working with Children Check framework is among the least flexible in the country. This is because the triggers for action in Victoria’s legislation require a ‘formal’ criminal charge, conviction, finding of guilt or substantiated disciplinary or regulatory finding. The Review notes that regulation changes have recently been made to allow the Working with Children Check screening authority to recognise prohibition notices that are issued by the ECEC Regulator in relation to an individual. This was a necessary change but more needs to be done.

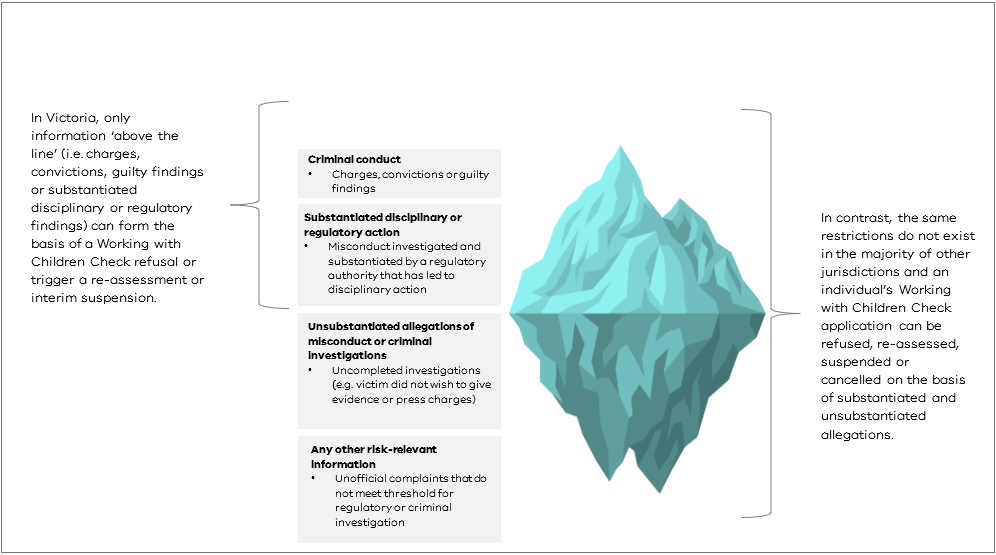

Figure 4.1 below shows the limitations of Victoria’s framework, also highlighted by the 2022 Victorian Ombudsman report.

This over-reliance on ‘above the line’ information—that is, criminal history (charge, conviction or finding of guilt) or substantiated disciplinary or regulatory findings—means that ‘red flags’ are missed, and an incomplete picture of risk is formed.

This approach is problematic because it is often in the pattern of behaviour or repetition of incidents (which on their own may not be considered sufficiently serious or evidenced for substantiation) that risks to children become evident.

The rigid nature of Victoria’s Working with Children Check assessment and outcomes framework is further illustrated in the Table 4.1 below.

| Criteria | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|

Category A Some discretion permitted

| Individuals subject to sex offender reporting obligations. Individuals charged with, convicted or found guilty of very serious offences such as murder, rape or sexual offences against children. | Clearance must be refused save for exceptional circumstances. |

Category B Some discretion permitted

| Individuals charged with, convicted or found guilty of serious offences such as serious violent and drug offences and sexual offences against adults. | Clearance must be refused unless granting it would not pose an unjustifiable risk to child safety. |

Category C Some discretion permitted

| Individuals charged with, convicted or found guilty of offences not identified in Category A or B. Individuals subject to relevant disciplinary or regulatory findings. | Clearance must be granted unless:

|

Other No discretion permitted

| Individuals who have not been charged with, convicted or found guilty of any offences and who have not been subject to relevant disciplinary or regulatory findings. For example, a person who:

| Clearance must be granted. |

Specifically, the following areas must be improved:

- Below the line matters: Most other child-safety screening authorities across Australia can consider and refuse a person’s Working with Children Check application based on information that falls below the threshold of charge, conviction, finding of guilt, or regulatory or disciplinary finding. This should also be the case in Victoria for individuals who pose a genuine risk to child safety.

- Triggers for a reassessment: In Victoria, the triggers for a Working with Children Check re-assessment are relatively limited and include where the screening unit is notified that a person, since receiving their clearance, has been: charged, convicted or found guilty of a Category A, B or C offence; subject to a relevant disciplinary or regulatory finding including a substantiated finding of reportable conduct; or excluded from child-related work by an interstate child-safety screening authority. By contrast, other interstate screening authorities have greater scope to re-assess a person’s suitability to work with children (for example, when there are unsubstantiated allegations but credible information).

- Suspension: In addition, Victoria’s worker screening legislation does not permit immediate suspension of a person’s clearance pending a re-assessment (for example, while an investigation is underway), except in limited circumstances involving very serious offending. Again, this is less protective than legislation in New South Wales, which allows an interim bar to take effect immediately where there is a real and appreciable risk of harm to children pending a re-assessment or completion of an investigation.

Taken together, the rigid parameters of Victoria’s Working with Children Check legislative framework mean that unsubstantiated but credible information or intelligence that point to child safety risks cannot trigger a re-assessment, nor can these ‘red flags’ provide a statutory basis for immediately suspending or revoking a person’s Working with Children Check clearance.

Victoria’s Working with Children Check framework needs to be re-calibrated to better protect child safety.

The Victorian Government will need to ensure that the threshold for refusing or revoking someone’s Working with Children Check clearance complements the threshold for removing someone from the Early Childhood Worker Register, as both these thresholds need to work together as part of a graduated continuum.

Another shortcoming with Victoria’s Working with Children Check scheme that was raised with the Review is the need to change legislation to require organisations to verify that they have engaged a Working with Children Check clearance holder either on a professional or volunteer basis. Currently, the onus is on the Working with Children Check holder to inform the screening authority that they are working or volunteering with an organisation to ‘link’ that organisation to their Working with Children Check. If a change is made to a person’s Working with Children Check status—for example, if it is suspended or revoked—only ‘linked’ organisations are informed. If an individual has not ‘linked’ an organisation, there is a risk that the individual could continue working or volunteering and presenting an ongoing risk to children. Victoria’s Working with Children Check legislation should be changed to require organisations to verify or validate when they have engaged someone to undertake child-related work. This will help provide accurate historical and current information of volunteer or worker movements across different organisations. This change should be considered in the work to create the National Register as it may provide efficiencies in the identity verification and entry of data about individuals.

4.1.1 Closing review loopholes in relation to Working with Children Check decision-making

Currently, a person who has had their Working with Children Check refused or revoked can generally seek a review of that decision via the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal. There is a limitation on the right to review a Working with Children Check decision where a person has been charged, convicted or found guilty of a Category A offence.

New South Wales has recently introduced legislation removing external pathways of appeal to its equivalent civil and administrative tribunal on the basis that its Office of the Children’s Guardian is best placed as a child safety specialist body to review and assess risk.

Victoria should look at how it can close any review loopholes that undermine child safety. People who have been subject to an adverse decision relating to a Working with Children Check should be able to have another person check that decision. However, this should be done by people who have specialist expertise in child safety. Like New South Wales, Victoria should create an internal review process, involving decision-makers who have the specialist skills and knowledge to approach these important decisions through a child safety lens. This should replace the current review pathway to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

All of the changes recommended above will likely require much more manual intervention by Victoria’s Working with Children Check screening authority compared to the largely automated Working with Children Check assessment framework that currently exists. At present, Victoria’s Working with Children Check screening authority is approximately one-third the size of its New South Wales equivalent (which has 85 assessors plus a separate compliance team), and around half the size of Queensland’s screening authority (60 assessors). While Victoria’s staffing numbers may have been appropriate under existing Working with Children Check settings (given the largely automated nature of the current rigid Working with Children Check assessment framework), there will need to be an uplift in staffing to support the new ways of working envisaged by this Review.

4.1.2 Mandatory training and testing as part of the Working with Children Check application process

No Australian jurisdiction currently requires mandatory training or testing as part of their Working with Children Check application process. This is a missed opportunity, given it is everybody’s responsibility to know the signs, listen, believe, and act in response to child abuse. In 2023-24, there were approximately 350,000 Working with Children Check applications in Victoria—this presents a useful window to raise awareness of child abuse, and support community-wide prevention and early intervention efforts.

The Review heard that the broader community still lacks the required understanding to recognise, identify, and adequately act to protect children from abuse and neglect. Research into community attitudes confirms this.

In the same way other industries require mandatory training and assessment (for example, those wanting to serve alcohol in the hospitality industry must undertake training to hold a Responsible Service of Alcohol Certificate), incorporating mandatory online training and testing as part of the application process would improve the competence of those holding a Working with Children Check. This training and testing need not be onerous. It could be delivered online and informed by contemporary best practice and evidence. Importantly, it is a practical way to empower every adult working with children to play their part in keeping children safe from harm.

4.1.3 National harmonisation

The Review heard strong support for a national approach to Working with Children Check to close gaps in the various systems across the country. While national standards for Working with Children Checks were endorsed by the Commonwealth Government and all states and territories in 2019, these standards only reflect minimum features of Working with Children Check schemes. They do not address the absence of national information sharing and a database to enable continuous monitoring of clearance holders against police information, disciplinary findings and other information nationally.

To address these issues, the Review recommends national advocacy by the Victorian Government for the Commonwealth Government to, and other state and territory governments to prioritise information sharing reforms including investment in a national database to support continuous monitoring of Working with Children Check clearance holders and exclusions.

Recommendation 6: Working with Children Checks 6.1 Change the Working with Children Check regulatory framework to: a) Allow unsubstantiated information or intelligence (for example, from police, child protection or other relevant bodies) to be obtained, shared and considered to assess, refuse, temporarily suspend or revoke a Working with Children Check. b) Permit a Working with Children Check re-assessment when the screening authority is notified or becomes aware of new unsubstantiated information or intelligence. c) Require organisations to verify or validate that they have engaged a Working with Children Check clearance holder to provide accurate historical and current information of movements across different organisations. 6.2 Create an internal review process for Working with Children Check decisions and remove the ability to seek review at the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal. 6.3 All applicants must complete mandatory online child safety training and testing before being granted a Working with Children Check. 6.4 Fund the Working with Children Check screening authority so it is resourced to undertake more manual assessments and interventions under new Working with Children Check settings, noting any efficiencies delivered by the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability (see Rec 8.1). 6.5 Work with the Commonwealth Government and other state and territory governments to develop a national approach to the Working with Children Check laws and advocate for an improved national database that is able to support real-time monitoring of Working with Children Check holders. |

4.2 Improving the Reportable Conduct Scheme

The Reportable Conduct Scheme and Working with Children Check are intended to work together to protect children from abuse and harm.

The overarching intent of Victoria’s Reportable Conduct Scheme is to make organisations safer for children by improving the way organisations respond to allegations of child abuse and misconduct by its employees. This is known as reportable conduct and includes: sexual offences; sexual misconduct; physical violence against a child; any behaviour that causes significant emotional and psychological harm to a child; and significant neglect of a child. Reportable conduct is aimed at capturing a broad range of conduct including those behaviours that fall below a criminal threshold.

The Commission for Children and Young People currently administers the scheme in Victoria. Under the Reportable Conduct Scheme, heads of organisations must: notify the Commission for Children and Young People within 3 days of becoming aware of a reportable allegation; investigate the allegation; and at the conclusion of the investigation, submit findings and actions taken to the Commission for Children and Young People.

The Commission for Children and Young People’s role is to independently oversee how the organisation responds to the allegation. It also has statutory powers to share information with other regulators and the Working with Children Check screening unit. While the Commission for Children and Young People does have an ‘own motion’ power to investigate reportable allegations, this power is rarely exercised.

As primary administrator of the Reportable Conduct Scheme with a remit over approximately 12,000 organisations, the Commission for Children and Young People is in a unique position to identify concerning patterns of behaviour through Reportable Conduct Scheme notifications. Between 2017 and 2024, the Commission for Children and Young People received 8,122 mandatory notifications of reportable allegations containing over 20,137 allegations.[1]

Mandatory notifications to the Commission under the Reportable Conduct Scheme increased by 30 per cent between 2022–23 and 2023–24 but its base funding has not increased since 2018. The Commission for Children and Young People reports that 85 per cent of child abuse and harm investigations receive low or minimal oversight by the Commission.

The Review identified a number of ways the Reportable Conduct Scheme could be improved. Under current legislative settings:

- The Commission for Children and Young People has limited ability to share unsubstantiated reportable conduct allegations with the Working with Children Check scheme as a result of narrowly drafted provisions in the Child Wellbeing and Safety Act 2005 that constrain information sharing and the overarching restrictions placed on the Commission under the Commission of Children and Young People Act 2012. Limiting assessable information to substantiated findings enables ‘red flags’ to be missed leading to a piecemeal and incomplete picture of risk. This does not support child safety, and the Review recommends this be changed.

- Where a matter is substantiated, the Commission for Children and Young People can exercise its legislative discretion to not notify the Working with Children Check area. The Review was advised that this discretion has been applied in around 5 per cent of substantiated matters, which are not referred to the Working with Children Check area.

The Review recommends that this discretion to not notify the Working with Children Check area of a substantiated matter be removed. What can look like a minor incident when viewed in isolation can reveal a very different risk profile when considered in the context of other information.

4.3 National harmonisation

Victoria alongside New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Tasmania and Western Australia have all implemented Reportable Conduct Schemes. Queensland’s scheme is commencing progressively from July 2026.

Like the Working with Children Check, it is vital for regulators in different states and territories to work together to achieve the shared overarching objective of protecting children from abuse, despite some variance in design.

In the interests of minimising unnecessary duplication and effort across borders, the Review supports substantiated allegations and investigations being recognised across state/territory borders, especially where that reportable conduct is also captured under the Victorian scheme.

Recommendation 7: Change the Reportable Conduct Scheme to improve information sharing 7.1 Change the Reportable Conduct Scheme regulatory framework so there is a clear proactive power to share unsubstantiated allegations with relevant regulators and agencies, remove discretion to not share substantiated findings, and recognise a finding or investigation under another state or territory’s Reportable Conduct Scheme where the reportable allegation is also captured under the Victorian Scheme. 7.2 Fund the administration of the Reportable Conduct Scheme so that it keeps pace with demand and the number of notifications, noting any efficiencies delivered by the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability (see Rec 8.1). |

4.4 Bringing information about child safety risk together in one place

The Review heard multiple times that the ‘breadcrumbs’ of information about a person—including information which does not meet the relatively high thresholds for substantiated conduct, but which is nevertheless still concerning—is rarely able to be seen and acted upon because no one can see the whole picture. Currently the Working with Children Check scheme and Reportable Conduct Scheme sit in 2 separate entities. Valuable intelligence from the Reportable Conduct Scheme—particularly in the form of unsubstantiated allegations—is often unable to be accessed by the Working with Children Check screening authority, which means that incidents are viewed in isolation rather than in aggregate.

For this reason, there is benefit in consolidating the Reportable Conduct Scheme functions of the Commission for Children and Young People (which currently holds the most extensive information about individuals through reportable conduct notification) and the Working with Children Check screening authority (which has powers to assess, suspend or cancel a Working with Children Check and prevent a person from engaging in child-related work) into one place. The Review considers the administration of the Child Safe Standards should also be included in this consolidation.

The Review recommends that these functions be brought together in a single entity and considers the Social Services Regulator would be an appropriate entity to administer them.

To support the consolidation, a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability must be developed to ensure an effective child safety net is in place. This capability must be able to draw on multiple sources of information, and the safe use of Artificial Intelligence should be looked at to allow information to be quickly scanned and patterns of concerning behaviour identified. Immediate steps should be taken to design and establish the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability. Together, these changes will significantly strengthen the safety net around children.

Equally as important, beyond up-to-date information and intelligence, the assessors responsible for exercising professional judgement of someone’s suitability to work with children must be well equipped to piece together and understand how the ‘breadcrumbs’ add up using evidence-based risk assessment tools and resources. The Review understands that the Queensland and New South Wales Working with Children Check screening authorities have embedded sophisticated clinically developed risk assessment tools administered by workforces that are resourced and supported through regular training and supervision. The Review considers this to be a critical gap in the current Victorian landscape.

This more joined-up approach—backed in by fit-for-purpose intelligence and risk assessment enablers—will better unify resources and ultimately, lead to better and more timely decision-making.

If designed well, the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability also holds the potential to streamline effort, minimise overlap and ensure investigative efforts are aligned, instead of duplicating each other.

The Review heard it can be challenging for the ECEC workforce to understand how and where to report concerning information, leading to both under and over reporting. The consolidation of Working with Children Check and Commission for Children and Young People Reportable Conduct functions must be supported by a ‘no wrong door’ approach, so any reports or concerns relating to the ECEC sector are promptly brought to the attention of the ECEC Regulator.

Given the likely scale of these reforms, with multiple legislative schemes requiring amendment, careful sequencing will be necessary to manage implementation risks.

Because predators exploit system loopholes and administrative gaps to target vulnerable people, the Victorian Government should consider how it can set up the new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability so in time it could support broader social services, disability services and aged care to offer the greatest protection to vulnerable Victorians.

Recommendation 8: Establish a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability and bring child safety risk information together in one place 8.1 Invest in the design and establishment of a new Shared Intelligence and Risk Assessment Capability that: a) provides up-to-date information to join up the ‘breadcrumbs’, including opportunities to use new technologies such as Artificial Intelligence that can quickly scan information and flag patterns of concern b) equips assessors with fit-for-purpose risk assessment tools so they can exercise sound judgement about an individual’s suitability to work with children; and c) complements and works together with other regulatory schemes so there is a common foundation across social services, disability and aged care to better protect vulnerable people. This new consolidated approach should deliver:

8.2 Bring together administration of the Working with Children Check and Reportable Conduct schemes in a single entity to strengthen the safety net around children. |

Updated