- Date:

- 9 Feb 2022

Acknowledgements

Aboriginal acknowledgement

The Victorian Government acknowledges Victorian Aboriginal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and water on which we rely. We acknowledge and respect that Aboriginal communities are steeped in traditions and customs built on a disciplined social and cultural order that has sustained 60,000 years of existence. We acknowledge the significant disruptions to social and cultural order and the ongoing hurt caused by colonisation.

We acknowledge the ongoing leadership role of Aboriginal communities in addressing and preventing family violence and will continue to work in collaboration with First Peoples to eliminate family violence from all communities.

Victim survivor acknowledgement

The Victorian Government acknowledges victim survivors. We keep at the forefront in our minds all those who have experienced family violence or other forms of abuse, and for whom we undertake this work.

Family violence support

If you have experienced violence or sexual assault and require immediate or ongoing assistance, contact 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) to talk to a counsellor from the National Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence hotline.

For confidential support and information, contact the Safe Steps 24/7 family violence response line on 1800 015 188.

If you are concerned for your safety or that of someone else, please contact the police in your state or territory, or call Triple Zero (000) for emergency assistance.

Message from the Minister for Prevention of Family Violence

I am pleased to present the Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management (MARAM) Framework annual report for 2020-21.

This report outlines activities by Victorian government departments, sector peaks and individual organisations to align policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with the MARAM Framework.

MARAM is a foundational and critical element of family violence reform, enabling a consistent and collaborative response to family violence. It is referenced in this report along with the two complementary reforms of the Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme (FVISS) and the Child Information Sharing Scheme (CISS).

I want to acknowledge the incredible commitment across government, our sector partners and broader service system to deliver this critical work, while at the same time managing and prioritising responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ending family violence remains a Victorian Government priority and implementing MARAM is a core element to achieve this. That’s why in the Victorian State Budget 2021-22, we invested $96.985 million in MARAM and the FVISS and CISS reforms over the next four years:

This includes:

- $35.1 million over four years to develop and deliver training, resources and tools to support implementation of the FVISS, the CISS and the MARAM Framework

- $15.3 million over four years to meet the demand for information sharing from courts, Victoria Police and Child Protection

- $17.2 million over four years for expert reform coordination teams in Family Safety Victoria (FSV) and the Department of Education and Training (DET)

- $29.4 million over four years for a range of change management, leadership strengthening and cross-sectoral collaboration activities to support universal health and education workforces.

The Family Violence Reform Rolling Action Plan 2020-23 will guide us through the next three years. It includes MARAM and Information Sharing as one of 10 priorities.[1] Other priorities under the plan include:

- Committing to a community-led response to end family violence against Aboriginal people, underpinned by self-determination.

- Improving access to safe and stable housing options for victim survivors.

- Developing a system-wide approach to keeping perpetrators and people who use violence accountable, connected and responsible for stopping their violence.

- Delivering an accessible and visible service for people experiencing family violence and children and families in need of support through The Orange Door Network.

The recruitment and retention of highly skilled and supported staff in specialist family violence and sexual assault services is essential for MARAM’s broader implementation across the service system. The success of our family violence reforms depends on the strength of the workforces that deliver them, and significant work is being undertaken under the Building from strength: 10-Year Industry Plan for family violence and response[2] to create a flexible, dynamic, and highly skilled workforce.

In the past year, work under the 10-year plan has included the introduction of mandatory minimum qualification requirements over a five-year transition period (in response to recommendation 209 of the Royal Commission into Family Violence). The policy outlines the qualifications required for new specialist family violence practitioners commencing employment in services funded by the Victorian Government from 1 July 2021.

The launch of the successful Family Violence Attraction and Recruitment Campaign and the development of a Jobs Portal for family violence roles has directly promoted the profile of work in the specialist family violence sector.

I would like to thank all ministers with framework organisations within their portfolios on the continued work being undertaken to align to MARAM during the 2020-21 financial year. This report is consolidated from my own portfolio report and the reports provided by:[3]

- the Hon Jaclyn Symes, Attorney-General

- the Hon James Merlino MP, Minister for Education, Minister for Mental Health

- the Hon Lisa Neville MP, Minister for Police

- the Hon Luke Donnellan MP, (former) Minister for Child Protection, (former) Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers

- the Hon Martin Foley MP, Minister for Ambulance Services, Minister for Health

- the Hon Melissa Horne MP, Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation

- the Hon Natalie Hutchins MP, Minister for Crime Prevention, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Youth Justice, Minister for Victim Support

- the Hon Richard Wynne MP, Minister for Housing

- the Hon Ros Spence MP, Minister for Multicultural Affairs

- Ms Ingrid Stitt MLC, Minister for Early Childhood.

I acknowledge the work of specialist family violence and sexual assault services and The Orange Door Network for the exemplary work they have continued to perform in response to family violence throughout these difficult times.

I also wish to acknowledge the work of peak bodies, Principle Strategic Advisors (PSAs), Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs) and other leading organisations across the state of Victoria. I would like to thank these organisations for leading the implementation of MARAM and the information sharing reforms and for the ongoing support that they have given other services.

Lastly, I thank all those across government, and sector colleagues across community services, police, justice, education and health for their continued work and dedication in improving our response to family violence, noting this has continued to take place despite the profound impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The collaboration as evidenced throughout this report helps drive the success of the reforms and reinforces the government’s commitment to ensure that safety of victim survivors is everyone’s responsibility.

[1] Victorian Government 2020, Family violence reform rolling action plan 2020-2023 https://www.vic.gov.au/family-violence-reform-rolling-action-plan-2020-…

[2] Victorian Government 2017, Building from strength: 10-year industry plan for family violence prevention and response https://www.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-05/Building-from-streng…

[3] Ministers listed were the portfolio ministers for the reporting period.

Whole of government snapshot 2020-21

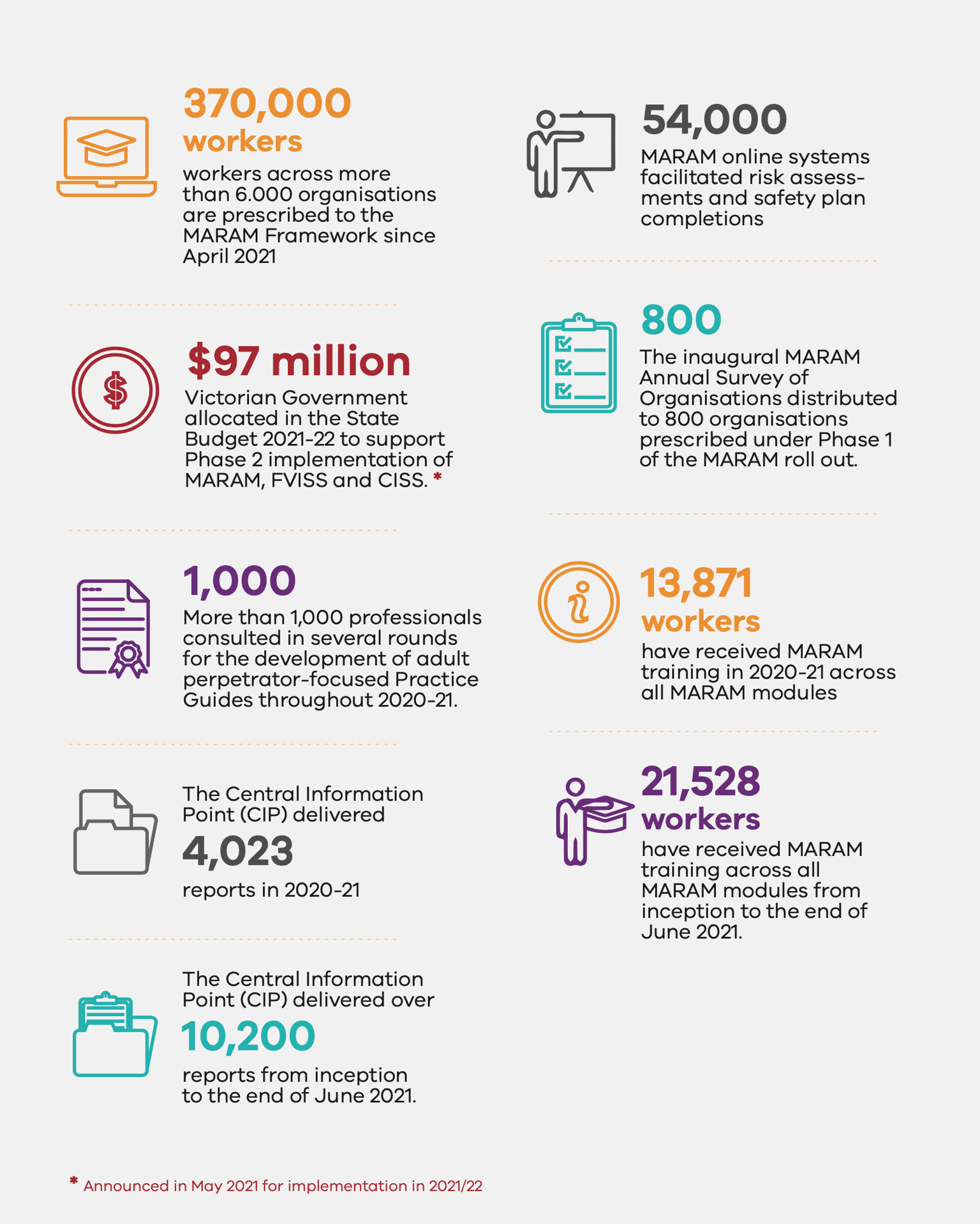

- 370,000 workers across more than 6,000 organisations are prescribed to the MARAM Framework since April 2021.

- MARAM online systems facilitated the completion of 54,000 risk assessments and safety plans.

- The Victorian Government allocated $97 million in the State Budget 2021-22 to support Phase 2 implementation of MARAM, FVISS and CISS*.

- The inaugural MARAM Annual Survey of Organisations distributed to 800 organisations prescribed under Phase 1 of the MARAM rollout.

- More than 1,000 professionals consulted in several rounds for the development of adult perpetrator-focused Practice Guides throughout 2020-21.

- 13,871 workers have received MARAM training in 2020-21 across all MARAM modules.

- 21,528 workers have received MARAM training across all MARAM modules from inception to the end of June 2021.

- The Central Information Point (CIP) delivered 4,023 reports in 2020-21.

- The Central Information Point (CIP) delivered over 10,200 reports from inception to the end of June 2021.

*announced in May 2021 for implementation in 2021/22.

Introduction

The MARAM Framework creates a response model for all services that connect with adults and children who may be experiencing family violence.

It covers all aspects of service delivery from early identification, screening, risk assessment and management, to safety planning, collaborative practice, stabilisation and recovery.

The objectives of the MARAM Framework are to:

- ensure that all professionals, regardless of their role, have a shared understanding of family violence and perpetrator behaviour, including its drivers, presentation, prevalence and impacts

- increase the safety of people experiencing family violence

- ensure the broad range of experiences across the spectrum of seriousness and presentations of risk are represented in the family violence response, including for Aboriginal and diverse communities, children, young people and older people, across identities, and family and relationships types

- keep perpetrators in view and hold them accountable for their actions

- provide guidance on how to align to the MARAM Framework to ensure consistent service delivery.

MARAM has been implemented alongside two other government reforms – the FVISS and CISS. FSV is the lead agency on the implementation of MARAM and the FVISS. DET is the lead agency on the implementation of the CISS.

Implementation of the reforms is broadly across three mechanisms:

|

FSV as the Whole of Victorian Government (WoVG) reform lead |

As the lead agency on the reforms, FSV is responsible for developing the overarching policy and guidance, as well as monitoring and reporting on overall implementation for MARAM. |

|

Departments as portfolio leads |

Government departments (and FSV as an administrative body) are responsible for tailoring and embedding the WoVG policy into their prescribed workforces while maintaining consistency to the reform intent. |

|

Sector leads |

Peak bodies and leading organisations in sectors receive funding to support implementation more directly with workforces, enabling a greater coverage to core sectors in the reforms. |

Where relevant, the chapters highlight the different roles played by FSV as WoVG lead, government departments and administrative offices as portfolio leads, and sector peaks and organisations.

- Chapters 1 to 5 provide further background on the MARAM reforms, use of language consistent with the MARAM Framework and the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Chapters 5 to 8 provide highlights and a summary of core activities across portfolios, structured around four strategic change priorities.

- Chapter 9 outlines the next steps being taken across portfolios to continue the reform implementation.

This report does not capture the full range of activities undertaken by government and sector, as the purpose is to provide a snapshot of achievements in MARAM alignment from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021.

Chapter 1: List of portfolios reporting

This table sets out the departments, Ministers, portfolios and program areas that are referenced in this report. See Appendix 1 and 2 for portfolios prescribed in Phase 1 and 2 respectively, and Appendix 6 for a more detailed description of each program area's work profile.

Phase 1 portfolios

The following portfolios and relevant services were prescribed to the MARAM Framework from 27 September 2018.

Table 1: Phase 1 Portfolios

| Minister | Portfolio | Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

|

The Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP |

Minister for Prevention of Family Violence |

|

|

The Hon. Jaclyn Symes |

Attorney-General |

|

|

The Hon. James Merlino MP |

Minister for Mental Health |

|

|

The Hon. Lisa Neville MP |

Minister for Police |

|

|

The Hon. Luke Donnellan MP |

(Former) Minister for Child Protection |

|

|

The Hon. Martin Foley MP |

Minister for Health |

|

|

The Hon. Melissa Horne MP |

Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation |

|

|

The Hon. Natalie Hutchins MP |

Minister for Crime Prevention Minister for Corrections Minister for Youth Justice Minister for Victim Support |

|

|

The Hon. Richard Wynne MP |

Minister for Housing |

|

Phase 2 portfolios

On 19 April 2021, MARAM, FVISS and CISS were extended to additional sectors, primarily health and education services. There are now over 370,000 workers across more than 6,000 organisations required to align with MARAM.[4]

Phase 2 is a significant step forward in the reforms as it reinforces the vision of the Royal Commission into Family Violence (the Royal Commission) regarding health and education workforces being authorised to share information to facilitate assessment and management of family violence risk to children and adults.

Due to the timing of the Phase 2 commencement within this reporting period, the newly prescribed portfolios are reporting on a three-month period only, 19 April 2021-30 June 2021.

Table 2: Phase 2 Portfolios

| Minister | Portfolio | Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

|

Ms Ingrid Stitt MLC |

Minister for Early Childhood |

|

|

The Hon. Jaclyn Symes |

Attorney-General |

|

|

The Hon. James Merlino MP |

Minister for Education |

|

|

The Hon. James Merlino MP |

Minister for Mental Health |

|

|

The Hon. Luke Donnellan MP |

(Former) Minister for Child Protection |

|

|

The Hon. Luke Donnellan MP |

(Former) Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers |

|

|

The Hon. Martin Foley MP |

Minister for Ambulance Services |

|

|

The Hon. Martin Foley MP |

Minister for Health |

|

|

The Hon. Natalie Hutchins MP |

Minister for Crime Prevention Minister for Corrections Minister for Youth Justice Minister for Victim Support |

|

|

The Hon. Richard Wynne MP |

Minister for Housing |

|

|

The Hon. Ros Spence MP |

Minister for Multicultural Affairs |

|

[4] Over 400,000 workers across 8,000 organisations when including organisations prescribed to the FVISS only, i.e., GPs.

Chapter 2: Use of language within this report

Adults, children and young people who have experienced family violence are referred to as victim survivors.

The word family has many different meanings. This report uses the definition from the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 (FVPA), which acknowledges the variety of relationships and structures that can make up a family unit and the range of ways family violence can be experienced, including through family-like or carer relationships (in non-institutional paid carer environments).

The term family violence reflects the FVPA and includes the wider understanding of the term across all communities. Dhelk Dja: Safe Our Way – Strong Culture, Strong Peoples, Strong Families defines family violence as an issue focused on a wide range of physical, emotional, sexual, social, spiritual, cultural, psychological and economic abuses that occur within families, intimate relationships, extended families, kinship networks and communities. It extends to one-on-one fighting, abuse of Indigenous community workers as well as self-harm, injury and suicide.

Family violence is a deeply gendered issue rooted in structural inequalities and an imbalance of power between women and men. While people of all genders can be perpetrators or victim survivors of family violence, overwhelmingly, perpetrators are men, who largely perpetrate violence against women (who are their current or former partner) and children.

Throughout this document, the term Aboriginal is used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Intersectionality describes how systems and structures interact on multiple levels to oppress, create barriers and overlapping forms of discrimination, stigma and power imbalances based on characteristics such as Aboriginality, gender, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, ethnicity, colour, nationality, refugee or asylum seeker background, migration or visa status, language, religion, ability, age, mental health, socioeconomic status, housing status, geographic location, medical record or criminal record. This compounds the risk of experiencing family violence and creates additional barriers for a person to access the help they need.

The term perpetrator describes adults who choose to use family violence, acknowledging the preferred term for some Aboriginal people and communities, as well as in practice, is a person who uses violence.

Adolescents who use family violence require a different response to family violence used by adults, because of their age and the possibility that they are also victim survivors of family violence. The term perpetrator does not refer to adolescents who use family violence.

Chapter 3: Legislation and regulations

Set out below is an overview of the legislation, policy and frameworks that support Victoria’s response to family violence.

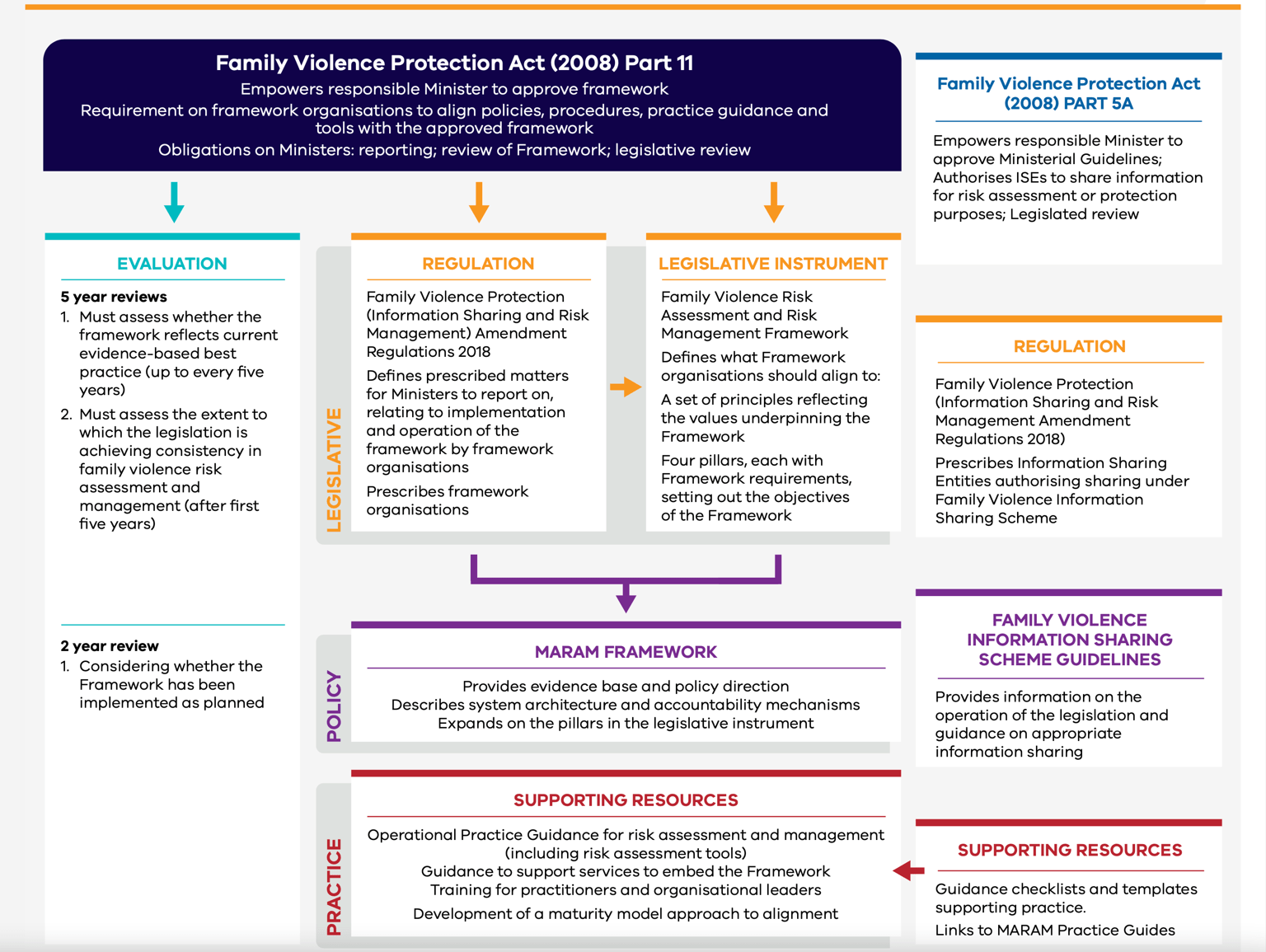

Figure 1 shows the legislative structure around the MARAM Framework.

The top line, in grey, refers to the legislation that enables the Minister to approve a framework for family violence response and require framework organisations to align with it, as well as establishing formal review mechanisms. The FVPA Part 11 contains the relevant provisions. Also referenced is Part 5A of the FVPA which relates to the FVISS.

The second line, in orange, references the various regulations and legislatives instruments that operationalise the legislation by listing the organisations that are prescribed to align with MARAM and FVISS, and defining the matters that are to be reported on by ministers and the core components of the framework.

The third line, in blue, summarises the core policy documents for the reforms, namely the MARAM Framework and the FVISS Ministerial Guidelines. Note that other policies relevant to MARAM implementation are referred to in this and previous reports including Everybody Matters[5], Dhelk Dja[6]and Nargneit Birrang[7].

The fourth and bottom line, in green, are the supporting resources that have been developed to help put the policy into practice. This includes guidance for practitioners, as well as embedding guidance for organisational leaders. This image only highlights the resources produced centrally by FSV as lead agency, and not the many tailored and updated resources applicable to various workforces. It is expected that the list of central guidance will continue to grow including guidance on working with adolescents who use violence in the home.

The left side of the image, in light blue, refers to the legislated five-year evaluation due in 2023, as well as the FSV-initiated two-year evaluation of MARAM undertaken by the Cube Group and referred to in this and the earlier 2019-20 annual report.[8]

[5] Everybody Matters: Inclusion and Equity Statement | Victorian Government (www.vic.gov.au)

[8] Noting the two-year review of FVISS by Monash University is also referenced in this and the earlier 2019-20 annual report.

Chapter 4: MARAM Framework structure

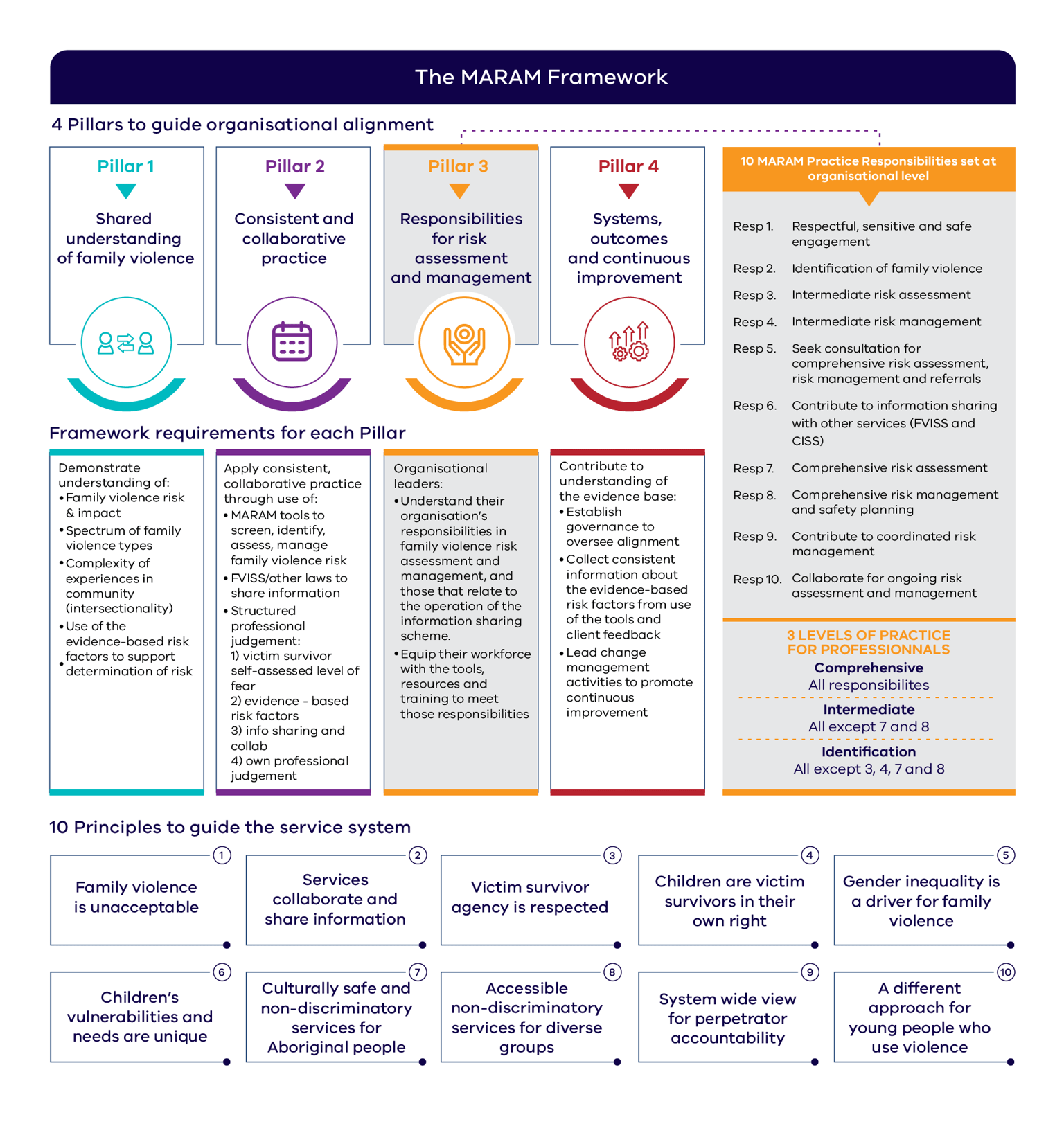

Figure 2 illustrates on a page the three core components of the MARAM Framework.

The image summarises the 10 MARAM principles.[9] MARAM is based on the belief that to provide consistent, effective and safe responses for people experiencing family violence, services need a shared understanding of family violence. To help achieve a shared understanding, the MARAM Principles help guide any response provided across the service system. The full text of the Principles can be found at Appendix 3.

The image also outlines the four MARAM Pillars and their requirements. The Pillars are set at an organisational level and are designed to build knowledge and skill and support the effective integration of a consistent, system-wide response to family violence. In aligning policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools with MARAM, organisations should refer to the 4 Pillars. Further details on the operation of the Pillars can be found in Appendix 4.

The right side of the image lists the 10 MARAM Responsibilities – these are contained within Pillar 3 which requires organisations to understand these responsibilities in their context and equip their workforces to meet the responsibilities. The full details of the Responsibilities can be found in Appendix 5.

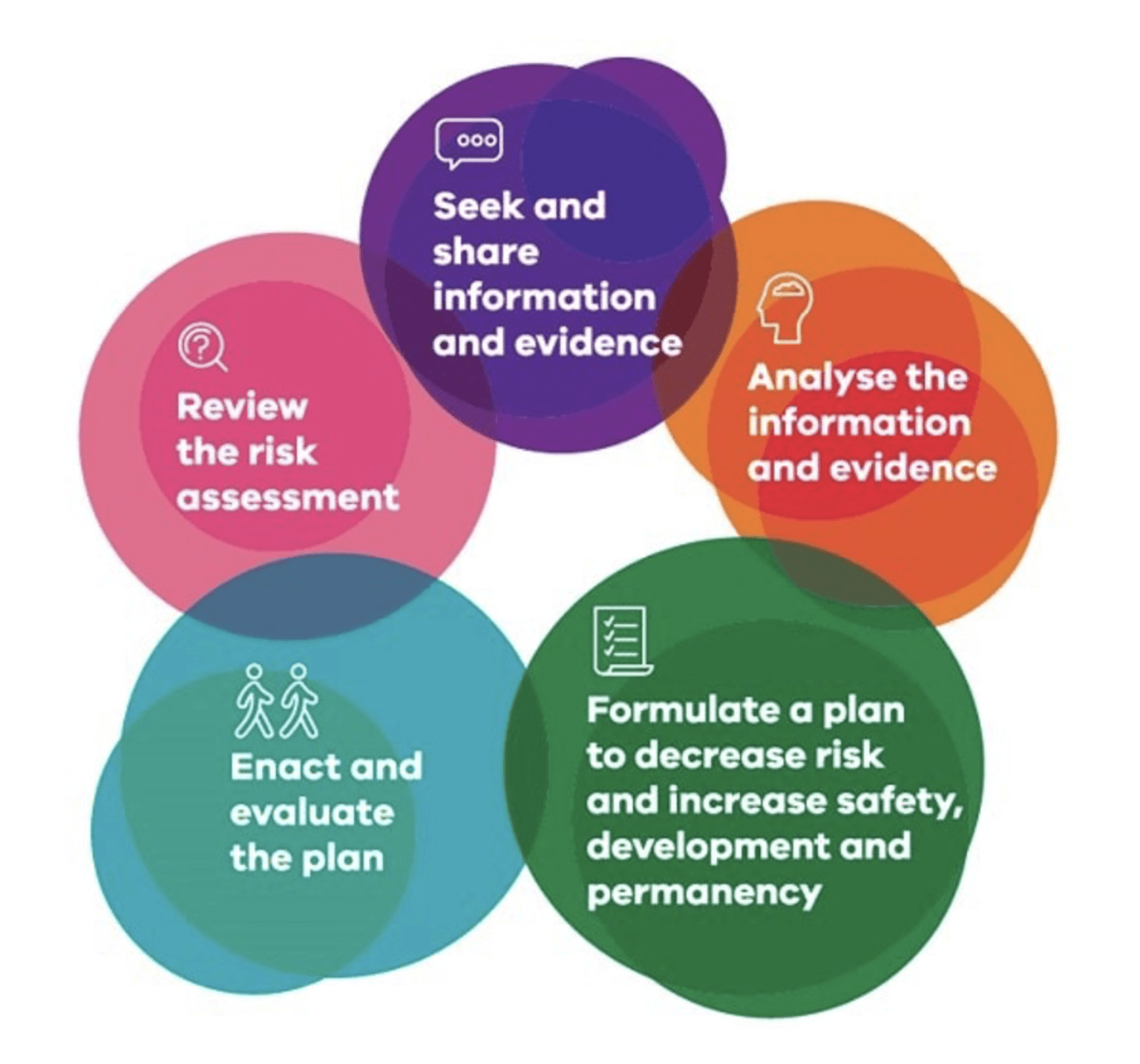

The responsibilities can be broadly summarised into three levels of practice:

- identification: MARAM Responsibilities 1-2, 5-6 and 9-10

- intermediate: MARAM Responsibilities 1-6 and 9-10

- comprehensive: MARAM Responsibilities 1-10

References to identification training (‘Screening and Identification’), intermediate training (‘Brief and Intermediate’) and comprehensive training (‘Specialist Practice’) are contained within this report.

[9] The full text of the principles can be found in Appendix 4.

Chapter 5: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

Throughout 2020-21 both metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria have been subjected to varying levels of restrictions. This created a dynamic and changing environment for services prescribed to implement MARAM. The commencement of Phase 2 for health and education workforces was postponed from September 2020 to April 2021 to account for the significant impact upon those particular workforces.

The COVID-19 pandemic saw an increase in the frequency and severity of family violence incidences in Victoria. This involves new forms of economic, emotional, and coercive controlling abusive behaviours[10]. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, new safety measures were implemented to reduce the spread of the virus within the community. Although necessary, these measures had implications such as social isolation, a known risk in family violence. It has also been noted that:

- there are new forms of intimate partner abuse towards women, including perpetrators having thought out strategies to attain social isolation (the threat and risk of COVID-19 infection)

- there has been an increase in coercion and control, social isolation, financial abuse, technology abuse, and the fear of contracting COVID-19.

Public health directions have attempted to balance the need to stay home with messaging that you can leave to attend a police station, court or for support or accommodation.

Despite the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, government departments and agencies continued to implement MARAM, in recognition of the important role all services have in the identification and management of family violence risk. Understandably, the pandemic disrupted implementation and alignment activities.

All workforces have seen a change to their working practice, including frontline community services organisations, specialist family violence and sexual assault services, The Orange Door Network, courts, Victoria Police, health services, education and community justice.

The recent report of the Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor (FVRIM) outlined the key changes and impacts of a number of initiatives during the COVID-19 response.[11]

These included:

- remote service delivery across the service system

- increased crisis accommodation

- the quick response of Safe Steps to develop an online access point, through a web chat function

- the Multicultural COVID-19 Family Violence Program, enabling multicultural, faith-based and ethno-specific organisations to receive appropriate support

- an increase in access to legal services for victim survivors through the launch of a family violence priority phone line

- the release of two COVID-19 specific advertising campaigns, ‘Respect Each Other: Call It Out’ and ‘Respect Older People: Call it Out’

- delivering online MARAM training for all workforces including e-learning and webinars

- embedding the MARAM screening tool in the hotel quarantine program

- family violence perpetrator programs for prisoners and community-based offenders adapted to remote service delivery

- the continuation of Operation Ribbon until December 2020 with Victoria Police Family Violence Investigation Units actively engaging with their highest-risk perpetrators and affected family members

- health and wellbeing key contacts assigned to government schools to increase support for vulnerable students.

Please note that all implementation activities and achievements for the 2020-21 reporting year may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, even where not directly referenced.

[10] https://awava.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Impact-of-COVID-on-DFV-Services-12-Nov.pdf

[11] COVID-19 response | Family Violence Reform Implementation Monitor (fvrim.vic.gov.au)

Chapter 6: Clear and consistent leadership

The MARAM reforms are now in their third year, and it is vital that change management continues to involve clear and consistent leadership by departments, supported by sector peaks.

The early evaluation of MARAM noted that central MARAM teams in government departments provided a strong foundation for leading the roll out of the reforms. This is supported by a clear and robust governance structure.

The additional funding provided directly to peak bodies and organisations means that departments can lead in practice direction, while trusted workforce leaders can work more directly with practitioners to support implementation.

This chapter is in three sections. Firstly, it describes the efforts by FSV as reform lead to provide central policy, resources and governance oversight to support implementation. Secondly, it focuses in on the leadership provided by departments to their sectors in guiding implementation. Finally, the report looks at the critical role of sector peaks and organisations in leading sector readiness and supporting the long-term cultural change necessary to implement and embed the reforms.

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

Highlights

- The Rolling Action Plan 2020-2023 articulated MARAM as a WoVG core foundational priority, and essential to developing a system-wide approach to perpetrator accountability

- The State Budget 2021-22 allocated a further $97 million over four years across relevant government departments and agencies to fund the continued implementation of MARAM, FVISS and CISS, with a focus on Phase 2.

- The regulations were amended on 15 December 2020, to enable Phase 2 organisations to commence under the reforms on 19 April 2021. These amendments prescribed organisations to MARAM, as well as to FVISS and CISS.[12]

Governance oversight and accountability

In direct response to an evaluation recommendation on MARAM implementation by the Cube Group, FSV revised and strengthened the governance and oversight arrangements. A MARAM and Workforce Directors Group oversees the implementation of MARAM (as well as FVISS and the Family Violence Industry Plan) and reports to a Project Reform Board. The Directors Group, chaired by FSV, provides regular project oversight of the reforms, including high-level tracking of expenditure, risks and issues of multilateral relevance, achievement of milestones and deliverables against agreed project plans.

The revised approach to governance provides a platform for strong and effective oversight of the implementation of MARAM activities, including monitoring of and responding to implementation challenges. In addition, sector grants implementation has been strengthened during this period by developing connected and clear working relationships and strengthening monitoring and performance management through quarterly reporting.

Oversight of actions to strengthen the perpetrator response has been strengthened through its inclusion as a domain in the Family Violence Outcomes Framework.

Perpetrator response

A significant area of work for FSV is in strengthening the perpetrator response through central policy development:

- Practice guidance on working with adults who use violence has been developed throughout 2020-21; with the release of the guidance in 2021-22. Chapter 7 contains additional details about the development of the guidance in supporting consistent and collaborative practice.

- Service guidelines, which outline a multi-intervention service response to perpetrators during the COVID-19 pandemic, were developed to support the continuation of work with perpetrators to ensure the safety of victim survivors. The guidelines were published in July 2020 and updated in November 2020 to align risk assessment, management and safety planning to MARAM.

- The perpetrator domain in the Family Violence Outcomes Framework, released in November 2020, was updated. The new outcomes and indicators contribute to consistent and collaborative practice (Pillar 2) by emphasising whole-of-system responses for holding perpetrators accountable and by driving integrated responses to support stabilisation for perpetrators and reduce risk (for example related to housing, mental health, the use of alcohol and drugs).

- A perpetrator accountability theory of change and monitoring and evaluation framework is being developed, contributing to a shared understanding of family violence (Pillar 1) by making clearer the full breadth of family violence (for example, including coercive control), which when measured will drive deeper understanding of perpetrators’ violent actions and patterns of behaviour, as well as systems, outcomes and continuous improvement (Pillar 4) through the improvements in collection and use of data and analysis.

Everybody Matters Statement and Implementation

FSV continues to fund initiatives that support members across Victorian communities, taking an intersectional approach in line with the Everybody Matters statement and leading the development of best practice.[13]

This includes:

- funding three Family Violence and DisabilityPractice Leaders in three Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH) areas in which The Orange Door Network is operational to build capability of The Orange Door and specialist partner agencies workforces, provide practice leadership and strengthen linkages and referral pathways with disability services

- developing and disseminating four new practice tools to help navigate the NDIS system, identify risk and protective factors related to the NDIS and tips for family violence and sexual assault practitioners when writing support letters and for communicating with the NDIS related to key NDIS processes

- How2 (‘Rainbow Tick ready’) inclusive practice training provided for over 100 specialist family violence sector organisations

- preliminary work in conjunction with DFFH to develop a WoVG strategy to respond to family violence committed against older people (elder abuse)

- in July 2020, a Multicultural Communities Family Violence Working Group, co-chaired by FSV and the Victorian Multicultural Commission, was established to support the 20 organisations funded under the Multicultural COVID-19 Family Violence Program. The Program is a joint initiative between DFFH and FSV, providing $2.4 million to 20 multicultural, ethno-specific and faith-based organisations across Victoria during the COVID-19 pandemic response and recovery to deliver family violence awareness raising, primary prevention and early intervention activities within their communities

- the development of the Aboriginal Family Violence Industry Strategy under Dhelk Dja, to provide a culturally informed framework to continue to build the capacity of Aboriginal services and its people in the family violence sector. Building on the strong foundations of experience in the sector, it will increase the number of Aboriginal people engaging in further education, prioritise Aboriginal led family violence programs and prevention initiatives and highlight the importance of Aboriginal culture in the sector.

Section B: Departments as portfolio leads

Highlights

- DFFH and Department of Health (DH) amended service agreements for funded organisations to include a new reference requiring prescribed organisations to align to MARAM.

- DFFH has established an internal MARAM Implementation Steering Committee to support a consistent approach to MARAM alignment and implementation across the department’s prescribed Community Services Operating Division workforces.

- DFFH has developed a series of behaviour statements (I-statements) to support practitioners to integrate MARAM Responsibilities into their practice and build confidence and competence in recognising and responding to family violence.

- DJCS Victim Services Support and Reform (VSSR) signed a memorandum of understanding with FSV to pilot the use of online tools for risk assessment and management for victim-survivors of family violence.

- DH established a Specialist Family Violence Advisor (SFVA) state-wide steering committee in November 2020 to provide state-wide support, direction and leadership of the SFVA positions, including ensuring the positions support MARAM alignment and implementation.[14]

- The Strengthening Hospitals Response to Family Violence (SHRFV) initiative has developed MARAM-aligned training and practice guidance to support front-line hospital staff to identify and provide early support to victim survivors of family violence. This means that staff report family violence risk as a standard part of their role, and it is built into hospital business as usual.

- DET’s Supporting Student Cohorts Affected by Family Violence Initiative (FVI) received the Evidence Based Policy Award at the IPAA Leadership in the Public Sector 2020 Awards on 20 April 2021. The FVI initiative achieved significant increases in school staff members’ levels of awareness, knowledge, skill and confidence to support students affected by family violence as well as increased identification and improved referral pathways.

- DET has signed on all Victorian government schools to the Respectful Relationships initiative, acquitting recommendation 189 of the Royal Commission into Family Violence. More than 1,950 Victorian government, Catholic and independent schools are participating in Respectful Relationships.

Department of Education and Training

More than 1,950 Victorian government, Catholic and independent schools are signed on to the Respectful Relationships whole school approach. This includes all government schools, acquitting recommendation 189 of the Royal Commission into Family Violence.

Respectful Relationships is a primary prevention of family violence initiative. It supports schools to promote and model respect, positive attitudes and behaviours and teaches students how to build healthy relationships, resilience and confidence.

Department Respectful Relationships Area staff provide on-the-ground support to schools, including project leads to guide implementation and liaison officers to support schools to respond to disclosures of family violence and implement FVISS and MARAM.

This is also supported by Respectful Relationships professional learning for early childhood educators. The professional learning aims to increase awareness and understanding of the dynamics of gender equality and family and introduces MARAM, FVISS and CISS.

The Supporting Student Cohorts Affected by Family Violence Initiative (FVI) was designed as a secondary or early intervention to build on the foundation laid by the Respectful Relationships Initiative.

The FVI was established in 2018 to develop evidence-based policy, along with practice guidance and resources for all school staff to assist them in providing an effective and early response to students who may be or are affected by family violence.

The objectives of the FVI were to:

- increase knowledge, skills, and confidence of school and regional staff (teachers, health and wellbeing specialists, leadership, and support staff) to respond to and support students who are experiencing family violence

- provide clarity and consistency on areas of responsibility for different roles within schools and the Department

- assist in development of referral pathways and service linkages

- contribute to the evidence base on early interventions to support school students who may be or are affected by family violence, including the processes for developing and implementing such supports.

DFFH: Child Protection

DFFH is developing a Strategy to Enable Practice Change. The strategy provides a considered and wholistic approach to support the implementation of MARAM and builds capability to recognise and respond to family violence risk.

To support practitioners to integrate MARAM responsibilities into their practice, the strategy contains ’I statements’ developed with the Victim Survivors Advisory Council (VSAC), including:

- When I see observable signs of trauma or assess there are safety risks, I ask the family violence screening questions in a place I know is safe for the client.

- I do not undertake screening and identification for family violence with the victim survivor when the person alleged to be using violence is present.

- I apply the Structured Professional Judgment Model to the information sought and shared through asking the risk assessment questions to determine the level of risk.

- I can describe high-risk factors, that based on the perpetrator’s behaviour and circumstances, have changed, or escalated in frequency or severity.

- I assess the risk to each child and young person independently and then consider this collectively with the risk experienced by the parent/carer and other children/young people to inform my determination of the level of risk for each family member.

DFFH: Multicultural Affairs

The Victorian Government is committed to ensuring that all Victorians, no matter their cultural identity, background or faith, feel accepted and free to participate fully in society. The actions taken by DFFH to support the first three months of alignment was to provide clear and consistent leadership to newly prescribed framework organisations across the multicultural and settlement sector to begin aligning their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools to MARAM.

- FSV has provided sector support funding to AMES Australia, Whittlesea Community Connections and Jewish Care to deliver tailored implementation support. The department is working closely with the three organisations, who have developed agreed deliverables for the 2021-22 reporting period.

- Information sessions were organised for the services by Multicultural Affairs, the Office for Prevention of Family Violence and Coordination, Office for Youth, and Family Safety Victoria (FSV) to introduce the operational aspects of MARAM and information sharing to support the identification, assessment, and management of family violence risk.

- An internal working group of departmental officials has been established to provide program-level oversight and support clear and consistent leadership in relation to the ongoing implementation of MARAM and the information sharing schemes by prescribed multicultural and settlement organisations.[15]

DH: Ambulance Victoria

The Ambulance Victoria Safeguarding Care Program has been established to oversee Ambulance Victoria’s approach to family violence, child safety and improvement activities that provide a safety net for victim survivors, children, vulnerable people and at-risk communities. The ‘Safeguarding Care Senior Lead’ will oversee the implementation and operation of MARAM across Ambulance Victoria by leading the work to identify which parts of Ambulance Victoria’s practice can be brought into alignment now and develop a longer-term plan to improve family violence risk assessment and management practice over time.

DH: Health services

Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (SHRFV) was established in 2016 to provide a system-wide approach to responding to family violence. Twenty-seven hospitals were funded to implement the initiative and provide mentoring and support to the remaining 62 public hospitals in a regional hub-and-spoke style model.

DH recognises the key role that SHRFV has played in supporting health services respond to family violence and the great opportunity to continue the important work through supporting health services alignment to MARAM. Prior to prescription the SHRFV initiative team had already developed resources to support organisational leaders adopt a stronger response to family violence and develop a MARAM action plan to be endorsed at the highest level.

Funding has been approved for SHRFV to support MARAM alignment until June 2024.

Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS): Corrections Victoria

Corrections Victoria (CV) has designed and published a Corrections Family Violence Programs and Services Guide which outlines clinical and non-clinical programs and pathways and the availability of CALD and Aboriginal specific services related to family violence.

To embed MARAM practice within Corrections Victoria’s funded service programs, many organisations have:

- committed to focus work on LGBITQA+ communities, women, trans and gender diverse people who have enacted harm and young people who have both enacted and experienced family violence

- applied intersectional analysis to understand clients as individuals with unique needs and experiences

- undertaken deeper clinical exploration in relation to marginalised groups, including gender affirming approaches and literature

- ensured that an intersectional approach is embedded into family violence practice

- dedicated specific resources to embed MARAM

- mapped programs and services against the MARAM responsibilities to guide work plans

- set up working groups to support MARAM alignment and the implementation of the FVISS.

Women’s prisons

Embedding a trauma-informed approach to prisoner management at Dame Phyllis Frost Centre and Tarrengower women’s prisons is a key area of reform to improve the gender responsiveness of the women’s prison system. Working in partnership with the women, understanding their lived experiences, including of family violence and how this can impact them in prison is essential to trauma informed practice.

CV has engaged a consultant to review and develop a new gender responsive, trauma informed training framework and associated packages, for custodial staff employed to work in the women’s system. The final packages were provided to CV at the end of the financial year, and implementation planning commenced in July 2021.

FSV: The Orange Door

The Orange Door is a free service for adults, children and young people who are experiencing or have experienced family violence and families who need extra support with the care of children.

During 2020-21 The Orange Door opened a further three sites in Central Highlands (October 2020), Loddon (October 2020) and Goulburn (April 2021). A further nine sites are planned in the 2021-22 period bringing coverage to all 17 DFFH areas.

The opening of an Orange Door is complex as it involves the establishment of local partnerships working in collaboration from one site to offer a multi-disciplinary response to family violence for those experiencing and using family violence, as well as for families with children in need. The implementation approach is continually adapted and strengthened based on the operational and implementation experiences in opening previous premises demonstrating a responsive leadership approach.

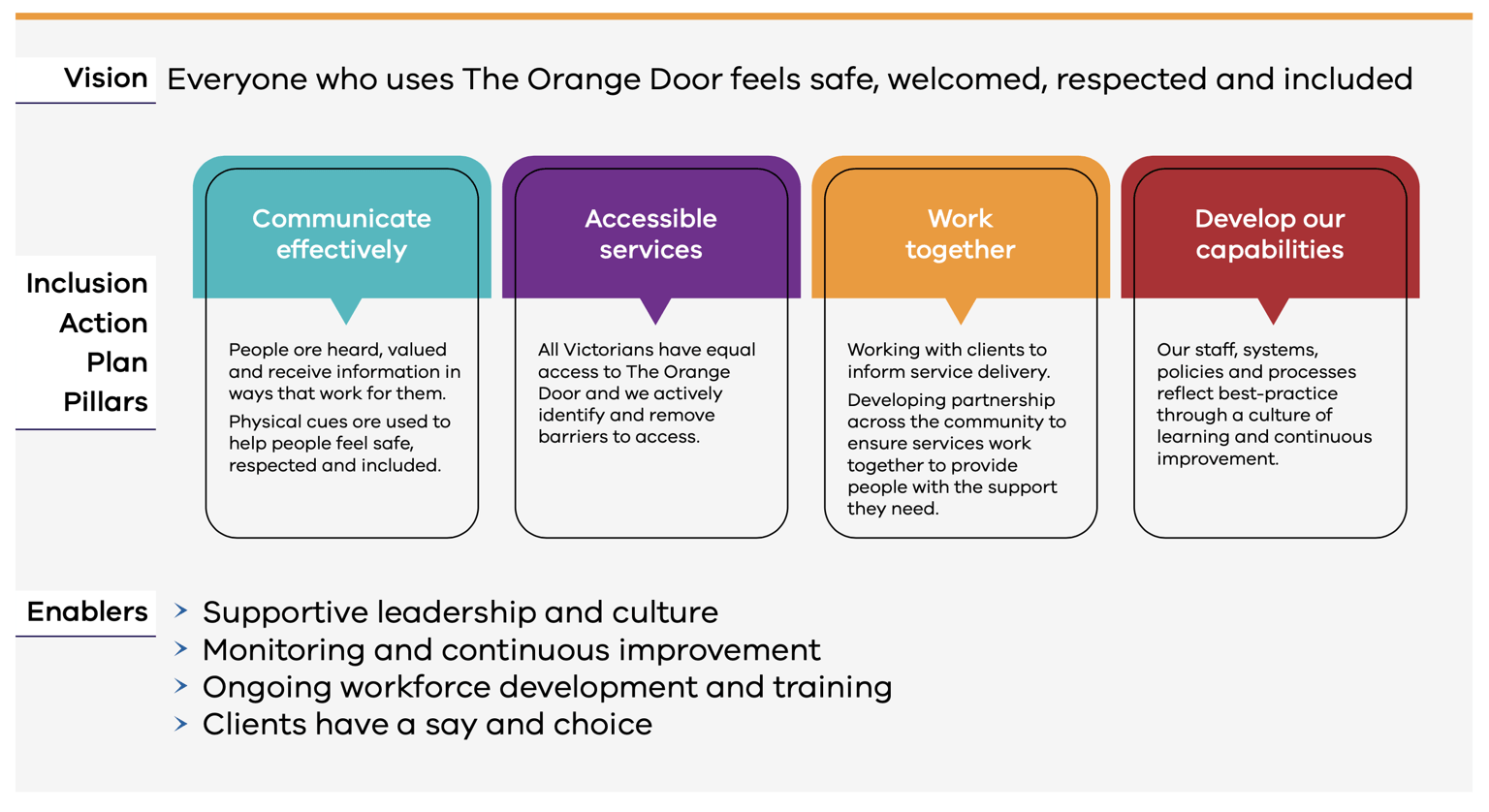

This can be demonstrated through the development of the Inclusion Action Plan for The Orange Door, which is a state-wide two-year plan to embed inclusion, access and equity in The Orange Door services. The plan was approved in April 2021 and outlines key measures to set the baseline so that everyone who uses The Orange Door feels safe, welcomed and respected. The plan supports The Orange Door partnerships to establish an intersectional approach to their work across family violence, sexual assault and child and family wellbeing in line with MARAM Principles.

The Aboriginal inclusion action plan is a three-year plan that focusses on actions The Orange Door services need to take to improve access and equity for Aboriginal communities.

This plan was endorsed by the Dhelk Dja Partnership Forum on 13 May 2021 and FSV will be consulting with ACCOs on the most appropriate approach to implement the plan, building from the Strengthening Cultural Safety of Family Violence Services project led by the Victorian Aboriginal Childcare Cooperative Agency. This will include the rollout of MARAM-aligned cultural awareness training and approaches to embed a continuum of learning for practitioners and partner agencies.

The Courts

The courts are aligning policies, procedures and processes with the MARAM Framework and MARAM implementation operational guidance. This work is supported by the MARAM operational sub-committee established in late 2020 which includes senior staff from the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria and the Children’s Court of Victoria who provide operational subject matter expertise.

The sub-committee supports:

- developing tailored guidance to help courts’ staff apply MARAM Responsibilities in their day-to-day roles

- supporting staff to use MARAM aligned tools and processes correctly and confidently

- providing opportunities for collaboration and information sharing among staff

- integrating MARAM tools in the courts existing IT and data capture systems to improve the efficient application of MARAM tools and processes and support information sharing.

The project team is working with the Case Management System (CMS) project to ensure the new court-information system provides an integrated solution to capture, store and share family violence risk related information across the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria and the Children’s Court of Victoria.

Victoria Police

A significant review of the Victoria Police Manual – Family Violence was completed in 2021. This was undertaken to ensure the policy directions for responding to family violence and assessing and managing risk are appropriate and aligned to community and sector expectations. During the period, practice guidance was developed to support the Family Violence Report (FVR) approach and promote consistency throughout Victoria Police. Further family violence practice guides are subsequently being reviewed, including the Victoria Police public-facing Code of Practice for Investigation into Family Violence.

Victoria Police actively collaborated with the sector on a number of family violence issues by participating in executive and senior manager level steering committees, advisory groups and workshops on specific family violence issues such as the misidentification of the primary aggressor at family violence incidents, perpetrator engagement by the sector, the operation of The Orange Door, and providing input to Family Safety Victoria for the development of practice guidance documents for victims and family violence support operators.

Following two years of staged implementation of the new Family Violence Report (FVR) (also known as an L17), stakeholder engagement indicates increased confidence by frontline police members in their decision making in response to family violence situations and more useful and fulsome narratives passed onto The Orange Door and other service agencies through the Department of Families, Fairness and Housings (DFFHs) L17 Portal.

In addition, Victoria Police has produced social media campaigns and accessible resources for culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities, translated into various languages and available in Easy English. These include:

- Information and Support Referralbrochure

- The Family Violence Safety Noticebooklet

- The Family Violence Safety Notice - Standard Conditionsinformation sheet

- The Family Violence: What Police do information sheets

- The Family Violence: Technical Terms Bilingual Tool

- A suite of videos in multiple languages(opens in a new window)

- The Reporting sexual offences to police booklet

The Victoria Police Practice Guide – Family Violence – Priority Community Response has been reviewed and updated, highlighting some of the key considerations for police members when responding to family violence situations within CALD communities applying an intersectional lens.

Section C: Sectors as lead

Highlights

- FSV funded $1.55 million of sector grants to provide direct implementation support to sectors prescribed under the MARAM, FVISS and CISS.

- FSV additionally allocated funds to three multicultural sector grant agencies to support the alignment of 41 migrant, refugee and asylum seeker settlement and casework services (that were prescribed in Phase 2).

- Funded recipients have delivered a variety of implementation activities throughout 2020-21, including Communities of Practice, webinars, practice forums and tailored resources. Further details are provided below.

Sector Grant Fund Recipients 2020-21

Sector grants were distributed to the same peak or representative bodies as in 2019-20 from Phase 1 workforces across the service system. This includes sector grants funding to mainstream peak bodies as well as separate funding and working groups for ACCOs.

- Justice Health

- Consumer Affairs Victoria

- Domestic Violence Victoria (DV Vic)[16]

- No to Violence

- CASA Forum (including Mallee Sexual Assault Unit)

- Council to Homeless Persons

- Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association

- Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare

- Municipal Association of Victoria

- Djirra

- Dardi Munwurro

- Elizabeth Morgan House

- Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Limited

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency

- AMES*

- Jewish Care*

- Whittlesea Community Connections*

*From April 2021

Some of the highlights of the sector grants recipients are outlined below under specific funding streams.

Safe and Equal - Formerly DV Vic and DVRCV[17]

During 2020-21 Safe and Equal delivered:

- Nine practice lead community of practice sessions based on a MARAM-aligned topic. The community of practice facilitated reflective discussions, guest speakers and peer-presented case studies.

- Four implementation champion group sessions were delivered, covering the code principles, MARAM Pillars and MARAM Responsibilities, and how they interrelate.

- Safe and Equal also supported No to Violence with the Family Safety Advocate community of practice. Topics covered included risk assessment in the unique context of the Family Safety Advocate role, information sharing, intersectional approaches, sexual violence in family violence, working with children and understanding child wellbeing.

No to Violence (NTV)

In partnership with SAS Vic and DV Vic, No to Violence facilitated four 90-minute online panels that explore sexual violence in family violence and coordinated high-risk responses between sexual assault services, victim survivor support services and perpetrator intervention services. The panels were recorded and circulated by the collaboration agencies.

In addition, NTV, in collaboration with the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare (the Centre) and DV Vic, facilitated three 60-minute online webinars with guest experts. The webinar themes explored coordinated risk management with children.

- 80 per cent of attendees reported an increased understanding of specific risk and protective factors that can exist across the life span.

- 60 per cent of attendees increased their understanding of how services can use the MARAM Framework to work together collaboratively.

- 90 per cent of attendees increased their understanding of how to maintain a child lens when assessing and responding to family violence risk.

- There has been an average of 86 per cent increase in understanding across the learning outcomes delivered and evaluated in each webinar. Summarising an overall increased understanding of sexual violence in intimate partner relationships and the barriers victim survivors from diverse communities encounter.

Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Ltd

The Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Ltd (VACSAL) has been successful in spreading awareness of MARAM though their respective networks. For example, VACSAL has consistently updated the Aboriginal Executive Council (AEC) on the rollout of the reforms. The AEC sits between the ACCOs and government and consists of key policy workers and CEOs from across the ACCO sector. Policy representatives are now more aware of the MARAM reforms, their progress and what the reforms mean for ACCOs.

During 2020-21, VACSAL engaged a consultant to produce a scoping paper exploring the enablers and barriers to implementing MARAM within the organisation and the ACCO sector more broadly. The scoping paper has advanced MARAM alignment by giving senior staff and FSV an insight into current barriers for MARAM alignment.

Sexual Assault Services Victoria

Sexual Assault Services Victoria (SAS Vic) has established and facilitated an online communities of practice for MARAM alignment. Three CoPs were completed with 60 SAS and harmful sexual behaviours (HSB) practitioners attending these sessions. The sessions included an overview of the family violence sector presented by The Orange Door Geelong, the DV VIC Ramps Coordinator and DV VIC representative as well as MARAM alignment in the HSB sector and application of the FVISS.

Elizabeth Morgan House

Initial resources created by Elizabeth Morgan House (EMH) aimed to build at internal alignment and capacity among EMH staff, including updating or creating new policies and procedures, adapting information-sharing templates, updating induction pack updates and delivering information-sharing training sessions. These resources and tools have been used to share more widely with other organisations, both Aboriginal and mainstream.

Dardi Munwurro and Djirra

Dardi Munwurro and Djirra have operationalised the MARAM Framework within their organisations and developed a shared understanding of the risks, experiences and impacts of family violence experienced by Aboriginal people. This work includes advocacy in mainstream forums for cultural safety to underpin family violence response across the services system, including recognition of the structural inequalities and barriers that Aboriginal people face when accessing support.

Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association

VAADA provides overall support to the AOD sector to embed and align with MARAM via many activities. VAADA supports capacity building, policy development and MARAM training across the AOD sector, and it has delivered secondary consultations, briefings, and information sessions to AOD organisations and clinicians from St Vincent’s Hospital and the Youth Support and Advocacy Service (YSAS) and AOD Intake and Assessment workers at Bayside Community Health. In addition, they present at various meetings to discuss the intersection between AOD services and family violence, including collaborative practice meetings with the Australian Community Support Organisation (ACSO) and Sector Capability Building Working Group meetings with Family Safety Victoria (FSV).

Specialist Family Violence Advisor (SFVA) Capacity Building Program in Designated Mental Health and Alcohol and Other Drug Services

The Royal Commission found alcohol and other drug services and mental health services play a direct role in identifying and responding to family violence. Therefore, building capacity was needed in these sectors to enable this and to strengthen relationships with specialist family violence services.

SFVA positions were developed in response to recommendations 98 and 99 of the Royal Commission into Family Violence:

Recommendation 98

The Victorian Government fund the establishment of specialist family violence advisor positions to be located in major mental health and drug and alcohol services. The advisors’ expertise should be available to practitioners in these sectors across Victoria.

Recommendation 99

The Victorian Government encourage and facilitate mental health, drug and alcohol and family violence services to collaborate by:

- resourcing and promoting shared casework models

- ensuring that mental health and drug and alcohol services are represented on Risk Assessment and Management Panels and other multi-agency risk management models at the local level.

The Victorian Government funded establishment of the SFVA positions across 17 areas in 2017. SFVAs embed family violence expertise within the alcohol and other drug and mental health sectors, support continuous improvement, lead system and practice change, and build sector capacity and capability to identify, assess, and respond to family violence.

State-wide coordination of the SFVA program throughout 2020-21 was primarily provided by No to Violence.

SFVA statewide coordination

Through close engagement on a Community of Practice undertaken throughout 2020-21, the Statewide Coordinator identified the need to form Special Interest Groups for the SFVAs to collaborate on key projects across the state.

Eight groups were identified with a focus on work to be conducted throughout the remainder of 2021 and into 2022.

Each SFVA sits on at least one of the eight special interest groups, though many sit on multiple groups. Where possible, the groups seek to collaborate with peak bodies and other key stakeholders.

One special interest group focuses on addressing barriers to refuge access for women using substances and experiencing mental ill-health. This group invited representatives from VAADA and DV VIC / DVRCV to join the group to provide their insights, identify advocacy opportunities, and support actions.

Another group is developing family violence newsletters, with a dual diagnosis perspective, for the mental health sector. In collaboration with the Centre for Mental Health Learning, which will host and distribute the newsletters, the group of SFVAs will write the quarterly newsletters.

The six other SFVA groups are currently scoping and planning their project goals and activities. These Special Interest Group topics will include:

- sharing insights to identify and respond to patterns of coercive control within mental health and AOD services

- secondary consultation models for SFVAs

- practice considerations for working with people who use family violence within AOD and mental health services

- demystifying MARAM and the information sharing schemes for the mental health and AOD sectors

- responding to family violence experiences and complexity with children and adolescents in mental health and AOD services

- MARAM-alignment recommendations for area mental health services, with a focus on tools.

Further examples of collaboration by SFVAs include:

- AOD Assessing with Confidence training - in collaboration with Turning Point trainers, SFVAs are co-delivering the AOD Assessing with Confidence training to provide specialist coverage of the family violence components of the updated, MARAM-aligned AOD Intake and Assessment Tools.

- Sexual Violence Awareness - two AOD SFVAs from EACH collaborated with the South Eastern Centre Against Sexual Assault (SECASA), Uniting, University of Sunshine Coast, and Resourcing Health and Education in the Sex Industry (RhED) to facilitate a cross-sector reflective practice discussion on linkages between substance use and sexual violence, MARAM risk indicators, non-physical indicators of sexual violence, and survival sex as a safety strategy.

- Overdose Awareness and Family Violence - on International Overdose Awareness Day, an AOD SFVA at EACH collaborated with SURe (Substance Use Recovery) to present a reflective discussion on the potential interplay between threats of overdose and family violence, including MARAM-aligned practice considerations to support a victim survivor and/or person at risk of overdose and invitation strategies.

Capability building grants (funding through the FV Industry Plan)

FSV is responsible for building capacity and capability in the specialist family violence sector but has also committed to using capability funding to support other MARAM-prescribed workforces across WoVG portfolios. All projects relevant to this work leverage MARAM alignment through creating a shared understanding of family violence, fostering consistent and collaborative practice, undertaking responsibilities for risk assessment and management and continuous improvements.

FSV-funded Youth Support and Advocacy Service (YSAS) for a second year to focus on young women’s experiences of intimate partner violence and non-collusive practice.

YSAS Highlights for 2020-21 include:

- identification of workforce needs required by the organisation to achieve family violence capability

- blended evaluation to confirm the design and deliver of training curriculum, informed by the pilot group

- executive-endorsed organisation wide YSAS statement of family violence

- development of a YSAS family violence resource book

- collaboration with NtV and CASA house to develop specialist training content to merge men’s behaviour change strategies with youth AOD frameworks and support disclosures of sexual assault for the youth AOD workforce at YSAS

Summary of progress

The far-reaching impact of these reforms across multiple workforces requires a clear and consistent leadership approach that involves both government departments and peak bodies and sector leads.

The role of central implementation teams located in each department was recognised by the 2021 budget outcome, and the provision of funding for four years will make an impact in time. As noted in the annual report for 2019-20, the main challenges following the successful budget outcome continue to be the challenge of recruitment and retention and completing priorities from other reform programs.

FSV will continue to take a centralised lead role and engage with departments on the roll-out of the reforms through the established governance structure.

[12] The 2020 regulations amended the Family Violence Protection (Information Sharing and Risk Management) Regulations 2018.

[13] Victorian Government 2018, Everybody Matters: inclusion and equity statement https://www.vic.gov.au/everybody-matters-inclusion-and-equity-statement.

[14] Approximately 19 SFVAs are in alcohol and other drugs (AOD) services (and approximately 21 are in mental health services).

[15] The internal departmental working group comprises representatives from the DFFH including from Multicultural Affairs, Office for the Prevention of Family Violence and Coordination, Office for Youth and Child Safeguarding.

[16] Note: Domestic Violence Victoria and Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria united to form Safe and Equal in November 2021.

[17] Note: Domestic Violence Victoria and Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria united to form Safe and Equal in November 2021.

Chapter 7: Supporting consistent and collaborative practice

Consistent and collaborative practice supports victim survivors to receive an appropriate response wherever they choose to access support. Consistent practice is achieved through work undertaken to develop (as WoVG lead) and embed (as portfolio and sector leads) MARAM policy into operational practice.

A consistent approach across the service system enables the development of collaborative practice– different sectors understand the best response to family violence and work together to achieve MARAM outcomes. To help achieve consistency, FSV creates centralised resources that are shared with departments and sectors, who then tailor and embed the resources into their workforces. To ensure that this consistency is maintained, FSV works closely with departments and sectors when they are tailoring the resources.

The Royal Commission identified that information sharing between services is essential for keeping a victim survivor safe and a perpetrator in view and accountable as part of collaborative practice. This is highlighted throughout this section. Information sharing is an organisational requirement under MARAM responsibility 6.

Section A: Family Safety Victoria as WoVG lead

Highlights

- Adult perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools were developed throughout 2020-21 in partnership with No to Violence and Curtin University, with consultations with more than 1,000 professionals.

- Use of online MARAM tools through all available platforms significantly increased in the reporting period, including a 72 per cent increase in risk assessments undertaken by The Orange Door using TRAM.

- Ongoing implementation of the Central Information Point (CIP), and expanding access to the CIP to Risk Assessment and Management Panels (RAMPs).

Perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides

Adult perpetrator-focused MARAM Practice Guides and tools were developed throughout 2020-21 in partnership with No to Violence and Curtin University. They draw upon a range of evidence and best practice models available across Australia and internationally to support direct intervention with perpetrators of family violence, including Tilting our practice,[18] Caring dads,[19] invitational narrative approaches,[20] transtheoretical model of change,[21] and various cross-jurisdictional reviews of perpetrator typologies.

The scope of the Practice Guides’ responsibilities also reflects the Everybody Matters statement and evidence provided by the Expert Advisory Committee on Perpetrator Interventions (EACPI) Report and the Centre for Innovative Justice’s mapping of roles across key workforces.[22]

FSV conducted a series of consultations throughout 2020-21 with more than 1,000 professionals, including specialist practitioners working with people using violence against Aboriginal communities, LGBTIQA+ communities, culturally, linguistically and faith diverse communities, older people and people with disabilities, academics, sector leaders and government departments.

The new perpetrator-focused resources support professionals to understand their responsibility for risk identification, assessment and management. They create new approaches to individual, service and system-level perpetrator accountability through better coordination of interventions across services as reflected in MARAM principle 9. The new resources also maintain a focus on victim survivors by recognising their experiences and the impacts of violence and coercive control while supporting interventions with perpetrators that reinforce victim survivors’ safety.

The perpetrator-focused resources are scheduled for release during 2021-22 with tailored training to follow.

Information Sharing Resources and Tools

Amendments to the FVISS Ministerial Guidelines were made on 19 April 2021 as part of the rollout of Phase 2. These amendments addressed the introduction of new entities into the FVISS under Phase 2 and provided further clarity regarding the operation of the FVISS in response to common questions received from ISEs. The guidelines are legally binding and apply to all ISEs.

The Central Information Point (CIP)

As the family violence system matures and the reforms improve family violence literacy across new and emerging workforces, there is increased capacity to identify the risk that perpetrators of family violence pose to family members and for the system to intervene to keep victim-survivors safe.

The CIP provides consolidated, risk-relevant information in one report to support frontline practitioners to assess and manage family violence risk. The CIP is currently available to The Orange Door Network, selected RAMPs and Berry Street Family Violence Services Northern Region. It brings together information about perpetrators of family violence from Victoria Police, Court Services Victoria, Corrections Victoria and Child Protection. The CIP aligns with MARAM Responsibility 6 (contribute to information sharing), Responsibility 9 (contribute to coordinated risk management) and Responsibility 10 (collaborate for ongoing risk assessment and risk management).

In addition to supporting more informed risk assessment and safety planning for women and children, the CIP is fundamental to the uplift in system capacity to keep perpetrators in view and ensure they are held accountable and risk management interventions are appropriately targeted. This is particularly important as the reforms are at a point where the system is increasingly shifting its focus to addressing perpetrators as the source of family violence, and to building a web of accountability around them. This is a key focus for the Family Violence Rolling Action Plan 2020-2023, which outlines the WoVG program of work under the Strengthening perpetrator accountability for family violence plan.

In addition to being integrated into the practice and operations of The Orange Door Network, the CIP is underpinned by FVISS, under the Family Violence Protection Act 2008. The CIP is also embedded within and is an enabler of a shared and consistent approach to identifying and managing family violence risk and supporting multi-agency risk assessment and management, in accordance with MARAM. The CIP provides a risk assessment and management tool that can be used in shifting attention away from the behaviours and actions of victim survivors to instead focus on stopping perpetrators from using violence and holding them accountable for their actions.

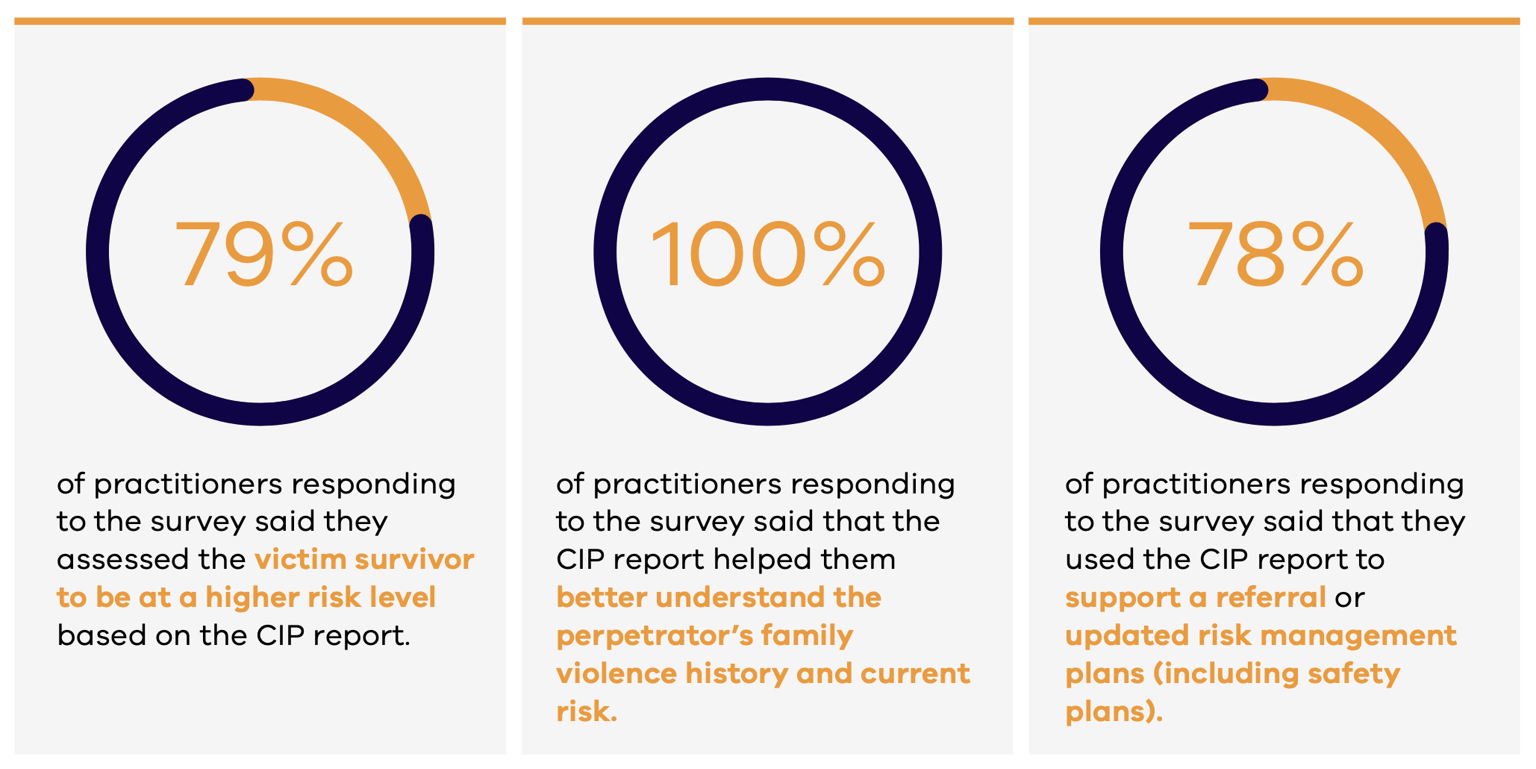

In June and July 2021, a survey was conducted with The Orange Door on the practice impacts of the CIP. FSV received 57 responses, from a mixture of roles across The Orange Door. This survey found the following:

In October 2020, the CIP was made available to the first set of RAMP areas as part of a phased rollout in response to a Royal Commission recommendation.[23]. The following RAMP areas have received training and guidance and now have access to the CIP:

- Western Melbourne

- Brimbank Melton

- Hume Moreland

- Outer Eastern Melbourne

- Ovens Murray.

CIP Case Study 1:

A RAMP coordinator was asked to case consult by a specialist family violence service. The victim survivor and perpetrator had a baby girl together. The perpetrator was engaged with The Orange Door due to family violence and other offences, and it was noted that the perpetrator was requesting to have regular contact with the baby. The RAMP coordinator submitted a CIP request to determine if this contact could take place safely. The CIP report showed a timeline of offences involving the perpetrator’s child from a previous relationship, as well as offences involving young people not related to him. The CIP report also demonstrated there had been limited system accountability around his use of family violence with past victim survivors and the harm caused to very young girls through sexual exploitation. As a result of information disclosed in the CIP report, agencies were able to advocate for support and conditions to be put in place for safe contact to take place.

CIP Case Study 2:

After a referral from Child Protection, the victim survivor, Teri, attended a specialist family violence service (SFVS) for an intake assessment. Teri had never reported or discussed the violence due to serious threats to her and her child’s life. She was also very frightened of the likely repercussions from the perpetrator if she reported the violence. Teri had also faced barriers to service engagement which affected her decision regarding how much information she was comfortable sharing with the service. Over a number of sessions Teri provided information regarding the serious and often life-threatening violence (including multiple strangulations). The SFVS determined there was a high risk and had concerns for the safety of both Teri and her young son. A referral to RAMP was made and due to significant gaps in the risk assessment and limited information regarding the perpetrator, a CIP report was requested.

From the CIP report, the RAMP co-ordinator learned that the perpetrator had a significant criminal history, including the use of weapons (hidden at the home) in previous family violence incidents. The RAMP coordinator also learned the perpetrator was a recidivist family violence offender who had used very serious violence against a number of intimate partners. This perpetrator also used high levels of violence in the community. Due to this information, RAMPs were able to determine a pattern and history of violence and a timeline of the family violence offending. This case was then accepted for a RAMP response where an appropriate risk management and safety plan was developed and implemented including for the management of the perpetrator.

Tools for Risk Assessment and Management (TRAM)

TRAM is used by practitioners in The Orange Door and a select number of specialist family violence agencies for risk assessment.

During 2020-21, 11,751 risk assessments were undertaken by The Orange Door practitioners using TRAM. This represented a 72 per cent increase on the previous year. This increase has been particularly strong for Child Risk Assessments with a rise of over 150 per cent over the last year.

This increase is driven by the increased caseload; however, there was also an increase in the proportion of cases that had a TRAM risk assessment, with 18 per cent of referrals received by The Orange Door having a TRAM risk assessment in 2020-21, up from 13 per cent in 2019-20 and 12 per cent in 2018-19.

Table 3: Number of MARAM risk assessments and safety plans undertaken by The Orange Door since commencement (using TRAM and the CRM)

| 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adult Comprehensive Risk Assessment |

4,417 |

5,879 |

9,343 |

19,639 |

|

Child Risk Assessment |

942 |

958 |

2,408 |

4,308 |

|

Safety Plan |

3,399 |

6,123 |

8,797 |

18,319 |

|

Total |

8,758 |

12,960 |

20,548 |

42,266 |

Specialist Homelessness Information Platform and Service Record System (SHIP)

SHIP is used by homelessness services and some specialist family violence services.

The MARAM tools in SHIP were first implemented in late August 2020. Over the period August 2020 to June 2021, 27,333 MARAM risk assessments and 6,061 MARAM safety plans were undertaken in SHIP. This amounts to over 33,000 MARAM risk assessments and safety plans undertaken by 237 different agencies over this period.

Table 4: Number of MARAM risk assessments and safety plans undertaken in SHIP since implementation

| 2020-21 | |

|---|---|

|

Screening tool |

529 |

|

Brief risk assessment |

1,161 |

|

Intermediate risk assessment |

899 |

|

Comprehensive risk assessment |

16,993 |

|

Child risk assessment |

7,751 |

|

Basic safety plan |

1,051 |

|

Intermediate safety plan |

407 |

|

Comprehensive safety plan |

3,907 |

|

Other safety plan |

696 |

|

Total |

33,394 |

In addition to online versions of the tools, many organisations are using their own adapted versions of the MARAM tools in paper or non-case management system format. Reflections on these tools from a VACCA practitioner show the benefits to practice:

Practitioner reflections from the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA)

The new MARAM tools provide a holistic framework to assist with identifying current risk as well as any historical intergenerational trauma to allow practitioners to design healing plans that respond to a family’s whole experience of family violence.

In terms of the Risk Assessment tool, practitioners have reflected that it is useful therapeutically in opening up conversations about and understandings of, family violence. A key aspect of this is how the tool supports the practitioner to continue to hear what the client is bringing and not to make a binary and/or essentialising judgement at the outset about who may be using or experiencing harm. Rather than being used all at once, practitioners find that it works best when used over a series of sessions and when revisited to reflect on shifts that have taken place around dynamic risk and safety.

Intersectionality Capability Framework and Tools

Improved understanding of structural inequality and discrimination is necessary for a robust understanding and implementation of Principle 3 of MARAM.

Embedding inclusion and equity: an intersectionality framework in practice was developed by FSV to support organisations to build capability in understanding and applying an intersectionality framework within their existing practice.