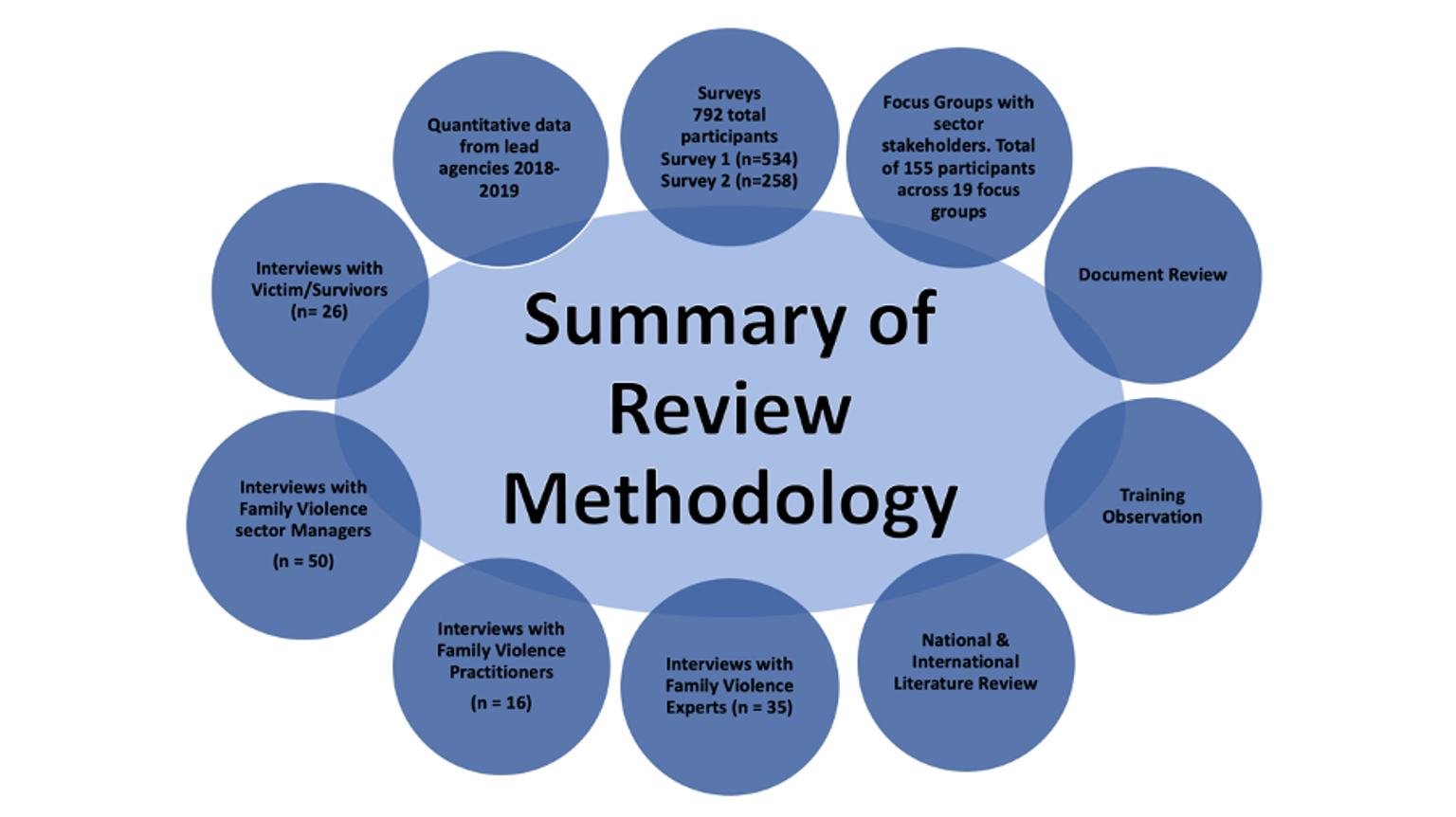

The research was guided by the seven key questions related to the implementation and outcomes of the FVISS. The research involved a multi methods approach including qualitative and quantitative methods, document review, training observation and a comprehensive literature review.

Review design, method and approach

The research designed included surveys, interviews, focus groups, document review, training observations, quantitative data from lead agencies, and a comprehensive national and international literature review. The diagram below captures the Review method.

Surveys were the primary quantitative method with two surveys used for this Review. While the surveys were both quantitative (multiple choice and scale responses) and qualitative (open-ended questions), the large number of quantitative questions means the survey focuses primarily on breadth over depth by capturing a large number of responses with limited capacity for detail. The surveys were designed to gain a broad understanding of practitioners’ experiences, attitudes and practices in relation to family violence information sharing and to enable some insight into shifts over time, post-implementation, regarding attitudes and practice.

In lieu of any existing and accessible Client Relationship Management (CRM) records which capture the history of family violence information sharing practice, a survey was considered the most appropriate method to collect baseline data. The items in the baseline survey, Survey One, were pre-FVISS measures of formal and informal information sharing practices and perceptions about information sharing in the Initial Tranche and Phase One workforces. Survey Two was undertaken with the Initial Tranche and Phase One approximately 12-18 months after implementation in order to capture the impact of the FVISS. Survey One questions were mapped to align with the Review questions that focus on the impact of the initial implementation of the FVISS. Outcomes and impacts of the implementation of the FVISS on information sharing were measured through Survey Two that provided data about changes benchmarked against the baseline established in Survey One. The survey design across Survey One and Two was a panel design, where we sought to analyse individual responses at two points in time, to more accurately measure change in practice and attitudes. However, the attrition rate between surveys was too high and the panel sample was not large enough to produce robust panel data. Therefore, the Report relies on broad trend data to review change between Survey One and Two regarding attitudes and practice.

Survey One included 83 questions and Survey Two included 95 questions. Both surveys comprised multiple choice, Likert-scale responses (i.e. questions with graded response options) and open-ended questions, which represent the surveys’ qualitative element. The surveys were conducted using Qualtrics. Survey One was piloted with 13 Victorian family violence practitioners and reviewed by Family Safety Victoria (FSV). Based on the feedback minor modifications to the survey were made prior to its release. Survey Two was reviewed by FSV. This data complements and captures broad attitudes and experiences, that align with the more detailed interviews and focus group discussions.

Quantitative data on the volume of post-scheme information sharing was requested and received from lead organisations; Victoria Police, DHHS, the Department of Justice and Community Safety, MCV and CCV. These organisations were asked how many requests for information they had received and made under the Scheme and details about which organisations were requesting information and which organisations they were sharing information with. Further details were also requested such as whether the information related to victim/survivors, perpetrators, children or others was requested and how many requests were denied. A month by month breakdown of the data was requested. There is a lack of of legislative obligation to record the volume of information sharing or details about such sharing under the Scheme. As a result of this, the data supplied by each of the lead organisations varied in content and format.

The qualitative part of the Review methodology (interviews and focus groups) was designed to capture in depth and detail the experienced and impact of the FVISS, to illuminate and explore key issues in the Review’s Interim and Final Reports. Qualitative research methods were used to understand the experiences, attitudes and practices of family violence information sharing. The qualitative methods involved interviews and focus groups that sought the perceptions, experiences and opinions of participants. These were undertaken in two periods; after implementation of the Scheme to the Initial Tranche and after implementation to Phase One. Qualitative research methods produce robust, rich and detailed data that is not readily available via quantitative instruments: they encourage disclosure and reflection amongst participants. The primary skills involved are attentive listening and facilitation of discussion that is simultaneously focused and open. Focus groups allow for the gathering of sufficient relevant information while openness ensures space for unanticipated opinions or information to be captured. A feature of qualitative research is that participants and interviewers or focus group facilitators jointly shape the discussion that takes place. In a process of reform such as the FVISS that is built on the existing expertise of practitioners and the knowledge and expert insights of those who have experienced family violence, such methods are particularly valuable.

Interviews and focus groups were based on semi-structured questions developed from the key Review questions (see Appendix Four). These questions were refined slightly after early focus groups and interviews. Semi-structured questions act as a guide to discussion rather than a firm schedule. In some cases, the interviewer/facilitator will ask each question on the interview schedule; at other times the interviewee or participant/s with a good understanding or strong opinions of the topic area, will cover all relevant issues with little prompting. In addition, participants may provide information they consider is relevant, even if it does not align directly with key questions identified by the interviewer/facilitator. In qualitative research, such additions are viewed as important data as they reveal the ways in which issues are understood by participants and can illuminate or point to ‘unintended consequences’ that may occur in practice.

Notes were taken of pertinent issues in focus groups and interviews with practitioners and experts and shared between Review team members. Trend data from the focus groups and interviews was used to aid discussion in future focus groups and interviews and as a way of focusing questions or seeking further data where relevant. Where focus groups were convened with specific organisations or sectors, discussion concentrated on those aspects most relevant to the knowledge and practise base of those participants (see Appendix Five for a list of focus groups). Where people were unable to attend a focus group they were invited to participate in a phone interview. Two Review team members typically attended each of the focus groups.

Participation by victim/survivors: This process was carefully managed to ensure appropriate and adequate recognition of participant needs. These participants are critical to the Review and the Report. Women were recruited through support services (family violence and disability services) and so had received the support of these services prior to their participation. Women were provided with vouchers to support their participation and in recognition of the provision of their expertise. The focus of the interviews was on women’s experiences of service responses, particularly as pertinent to the sharing of family violence information. The participants were not required to discuss their experiences of family violence. The interviewers have expertise in relation to the impact of family violence and the nature of the service and response systems. The victim/survivor participants had significant experience of having information gathered and/or shared as they interacted with various services. The victim/survivor participants had control over the timing and location of their engagement with the Review. Most were interviewed or attended focus groups at specialist family violence services, locations where they felt comfortable. Others elected to participate by phone in order to better ensure their contributions were confidential.

A wide range of relevant documents and data including training content, training participation and feedback, Enquiry Line data, stakeholder submissions, FSV plans, reports to FSV about the implementation of the FVISS and other relevant reforms, and relevant Regulatory Impact Statements, were reviewed. A comprehensive literature review was also undertaken to understand the international and national context in which family violence schemes have been implemented and to take into account the learnings of reviews of these schemes in other contexts.

The advantages of the multi methods design are that it allows for breadth (surveys and other quantitative data), depth (interviews and focus groups) and context (literature review). The documents, depending on category, provided context, quantitative data, or the views of stakeholders. The range of data sources allows for robust triangulation whereby the themes present in one data set can be matched, confirmed or contrasted with those from other sources.

Participants, data sources and analysis

Participants

There were more than one thousand participants in the Review over the two data collection periods. Two hundred stakeholders were interviewed or took part in focus groups and 792 people responded to the survey. Those who participated in focus groups or responded to the surveys included workers and managers in the Initial Tranche and Phase One organisations, family violence experts and victim/survivors. Family violence experts included family violence trainers, academics, those working in peak organisations, policy leaders, managers, family violence advisors and judicial officers.

Recruitment for the surveys, interviews and focus groups was facilitated through multiple pathways

These pathways included the Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre (MGFVPC) and FSV website, FSV newsletters, the MGFVPC monthly e-Digest, emails to all relevant peak bodies and government departments. Where FVISS training participants provided permission for their details to be shared for the purposes of recruitment to the Review these potential participants were emailed directly with an invitation to take part in the Review. Each survey was distributed through the same pathways via a survey link along with information about the survey and invitations to participate in the survey and share it with other practitioners if appropriate.

The participation of geographically diverse stakeholders was considered important. Four focus groups were held in regional or remote areas, including Shepparton, Sale, Bairnsdale and Geelong.

Victim/survivors were recruited through specialist family violence services. This process was designed to assist in ensuring that they were safe and adequately supported throughout their participation. Prioritising victim/survivor safety is the primary logic for the reform under Review. Such consideration is an integral part of an ethical approach to engaging with victim/survivor participants. Victim/survivors were provided with a $50 Coles voucher as recognition for their sharing of expertise and experiences.

All potential participants were offered the opportunity to participate by telephone or via email if attending a focus group or interview was not convenient or possible.

The Review did not aim for a representative sample; that is representation that mirrors proportionally the number of each category of ISE organisation. However, it did seek a wide range of views, thereby reflecting the diversity of organisational types included in the FVISS. Where participation by a particular category of ISE in the Initial Tranche or Phase One was not readily forthcoming efforts were made to recruit participations from these categories. Such efforts included direct contact with potential participants where details were publicly available, and, where appropriate, contact with a peak body, relevant government department, or particular ISEs.

Recruiting participants in the second period of data collection proved more challenging than in the first. Recruiting workers for focus groups and managers for interviews required more sustained effort and the participant numbers in Survey Two (258) were substantially less than for Survey One (534). One explanation for this may be ‘research fatigue’. Family violence practitioners and managers are being recruited to participate in multiple reviews, while services are facing increased demand and while implementing multiple reforms.

Initially it was intended that perpetrators of family violence would be included as participants in the Review. We anticipated that access to known perpetrators of family violence would be facilitated through Men’s Behaviour Change Programs (MBCP). However, despite best attempts and the willingness of men’s services to engage with the review, recruitment proved challenging. We note that No To Violence, the peak organisation for MBCP, was willing to assist with recruitment. In addition, the Review team have a number of established relationships with individual MBCP and these were contacted directly with requests to facilitate access to potential participants. However, sustained attempts to recruit perpetrators were unsuccessful. The barriers to recruitment included:

- the workloads of MBCP: many have substantial waiting lists. As a result of these pressures, a number of MBCP felt unable to commit to facilitating perpetrator involvement in the Review

- a not unreasonable perception that the open style of questioning involved in the Review interviews might undermine MBCP’ non-collusive approach, which focuses on providing a clear message about perpetrator accountability and the choice to use violence. Men’s services expressed a preference for engagement with the Review to be instructive for any men involved however, the Review questions were designed to illicit frank opinions, so questions needed to be open rather that suggestive of a ‘correct’ answer

- a belief that perpetrator participation in the Review should be supported with incentives such as gift vouchers, similar to victim/survivor participation. This proposition was not considered consistent with an ethical approach to research

For these reasons, the Review did not include perpetrators as participants, though it did include experts and practitioners involved in men’s services and MBCP. We note that internationally there is only limited engagement with identified perpetrators in family violence related research, particularly in the case of program evaluations and legislative reviews.

Survey

The survey component of the research involved two surveys: distributed over three waves, Initial Tranche and Phase One (Survey One), and post rollout of FVISS (Survey Two).

Across Survey One and Survey Two the participation rate dropped, from 543 for Survey One, to 258 for Survey Two. These numbers reflect completed surveys (defined as at least 75% of questions answered). Issues pertaining to participation rates and the longitudinal panel are detailed under Limitations. The data from Survey One and Two were analysed in Stata and Qualtrics primarily for trend analysis, comparing attitudes and differences in practice and issues related to training, with additional analysis of the qualitative, open-ended responses.

Interviews and focus groups

All the data gathered from participants in interviews and focus groups (other than victim/survivors, where they requested it) was audiotaped and transcribed using professional secure transcribers. Themes for analysis were developed based on the confluence, strength and frequency of the content of participant responses to questions, relevance to the research questions, and salience of the issues relevant to the research literature. These themes and sub themes or nodes were used to organise the transcripts of the focus group and interviews using nVivo software. Every piece of qualitative data (interview transcripts, focus group transcripts, and field notes where relevant) was ‘coded’ according to these themes. NVivo software allows for the capture of all data related to a specific theme and produces integrated reports: each of these reports are then analysed to produce key findings. NVivo coding means the weight of evidence under each theme can be clearly identified and drawn out, as every mention of a topic/issue is collated. This process allows researchers to draw firm and robust conclusions from rich and detailed qualitative data. The selected quotes in the Review reflect the weight of evidence under each of the themes, except where contradiction or diversity of view is specifically indicated.

Throughout the Report, we identify specific quotes according to category and indicate whether Expert Interview, Manager Interview, or Focus Group. The interview data from victim/survivors was transcribed and coded separately. Pseudonyms are used in the section on victim/survivors (section 8.1): descriptions attached to victim/survivor quotes are generic and any identifying details such as location or specific services have been altered or redacted to maximise security and privacy.

The table below provides details of Review participants.

Table 4: FVISS review participation

|

Research Method |

Category of Participant |

Number of Participants |

|

Surveys |

Workers in relevant services and organisations |

Survey One 534* (378 Initial Tranche and 156 Phase One)

Survey Two 258*

Total number of survey completions: 792 |

|

Interviews |

Service Providers

Managers

Experts |

16 interview participants (Initial Tranche)

20 interview participants (Initial Tranche) and 30 participants (Phase One)

14 interview participants (Initial Tranche) and 21 interview participants (Phase One)

Total participants: 101 |

|

Focus groups |

ISE workers |

11 focus groups, 95 participants (Initial Tranche)

8 focus groups, 60 participants (Phase One)

Total participants: 155 |

|

Focus groups and interviews with victim/survivors |

Victim/survivors |

8 interview participants and 2 focus groups, 10 participants (Initial Tranche) 18 participants total Initial Tranche

1 interview participant and 2 focus groups, 7 participants 8 participants total (Phase One)

Total participants: 26 |

|

TOTAL |

|

1074 participants |

* The survey figures indicate the number of participants who completed the survey. Completed in this context means that more than 75% of the survey was completed.

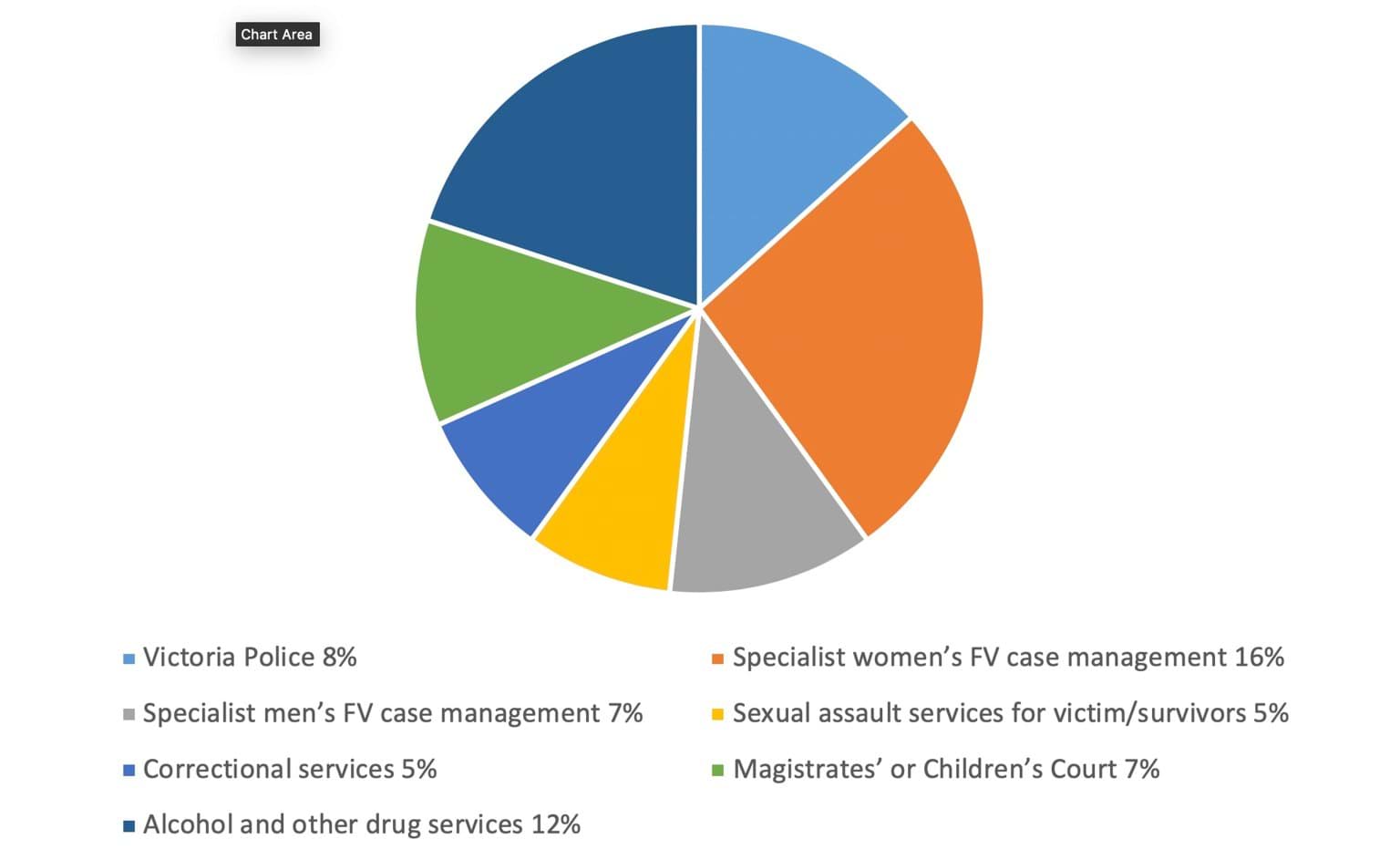

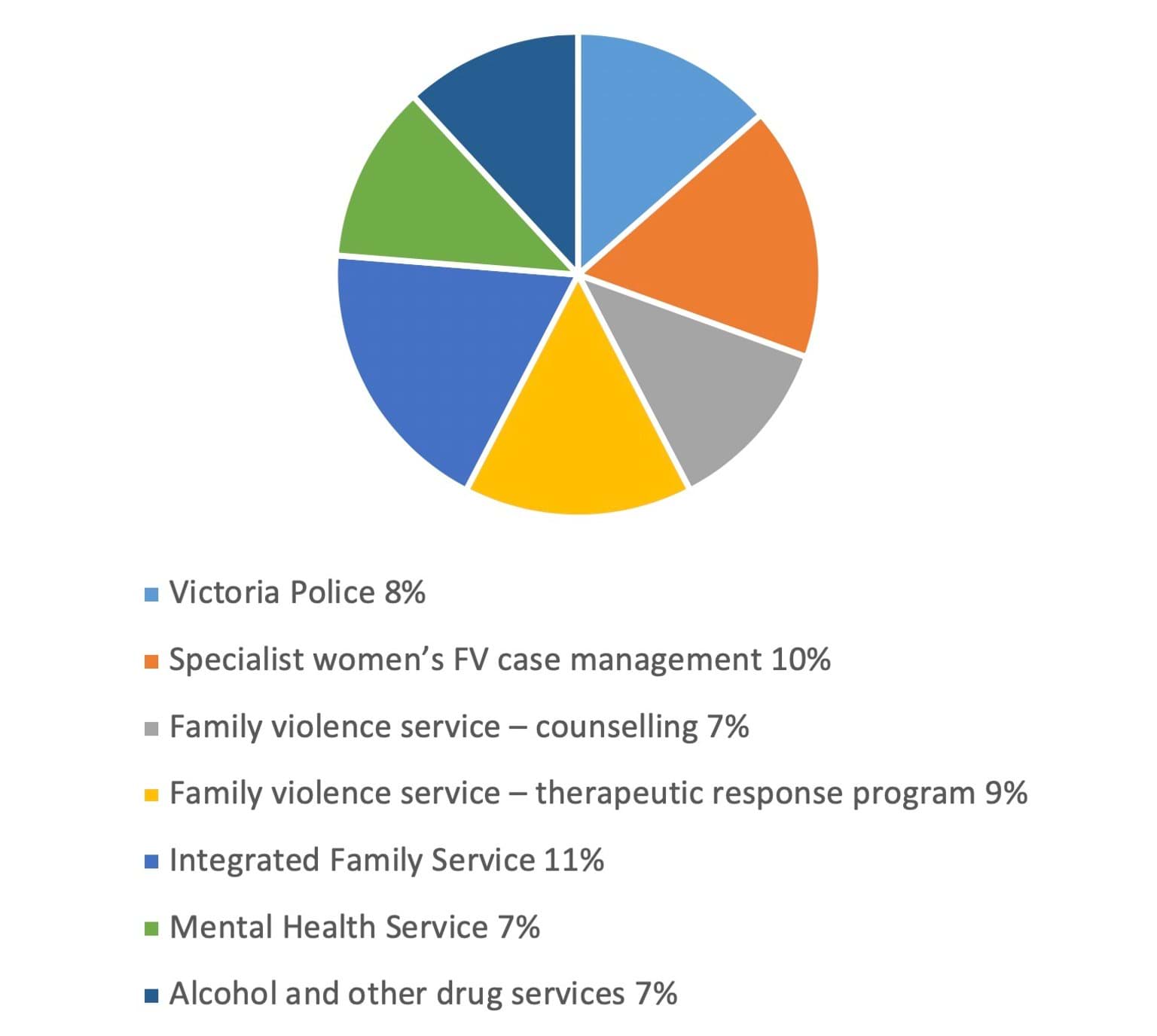

The charts below indicate the workplace of participants in Survey One and Survey Two

*Individuals from more than 25 organisations participated in Survey One, the chart reflects the most frequently represented workplaces. The full list of organisations can be found in Appendix Six.

* Individuals from more than 20 organisations participated in Survey Two, the chart reflects the most frequently represented workplaces. The full list of organisations can be found in Appendix Six.

Table 5: Survey one and two survey respondents

|

Answer |

SURVEY ONE (2017) |

SURVEY TWO (2019) |

||

|

|

Number |

% of survey respondents* |

Number |

% of survey respondents* |

|

Victoria Police |

41 |

7.55 |

8 |

8 |

|

DHHS |

7 |

1.29 |

2 |

0.78 |

|

Specialist women’s FV case management |

88 |

16.2 |

25 |

9.69 |

|

Specialist men’s FV case management |

36 |

6.63 |

10 |

3.88 |

|

Health Care Worker |

23 |

4.24 |

5 |

1.94 |

|

Child FIRST |

23 |

4.24 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

Child Protection |

7 |

1.29 |

4 |

1.55 |

|

Sexual assault services for victim/survivors |

26 |

4.79 |

3 |

1.16 |

|

Victims Assistance Program |

4 |

0.74 |

3 |

1.16 |

|

Correctional services |

28 |

5.16 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

Refuge |

7 |

1.29 |

2 |

0.78 |

|

Offender rehabilitation and reintegration services and programs |

4 |

0.74 |

5 |

1.94 |

|

Prisoner services or programs provider |

1 |

0.18 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

Magistrates’ or Children’s Court |

36 |

6.63 |

4 |

1.55 |

|

Victim Support Agency |

5 |

0.92 |

5 |

1.94 |

|

Risk assessment and management panel (RAMP) |

15 |

2.76 |

3 |

1.16 |

|

Alcohol and other drug services |

67 |

12.34 |

17 |

6.59 |

|

Family violence service – counselling |

5 |

0.92 |

17 |

6.59 |

|

Family violence service – therapeutic response program |

16 |

2.95 |

24 |

9.30 |

|

Homelessness services – access point, outreach or accommodation services |

4 |

0.74 |

3 |

1.13 |

|

Integrated Family Service |

9 |

1.66 |

29 |

11.24 |

|

Maternal and Child Health Service |

18 |

3.31 |

16 |

6.20 |

|

Mental Health Service |

12 |

2.21 |

18 |

6.89 |

|

Youth Justice |

6 |

0.91 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

Out of home care service |

5 |

0.92 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

Other |

46 |

8.47 |

35 |

13.57 |

|

Total |

543 |

100.00 |

258 |

100.00 |

Relevant documents were collected throughout the course of the Review. These documents were typically supplied proactively by FSV, provided by ISEs and peak bodies or identified as available through various means, such as the FSV website or stakeholder engagement. The documents were read and analysed to provide context and relevant information and as a means of triangulating the data gathered from participants. A full list of the documents consulted is provided in Appendix Two.

Ethical assessment

Ethics approval was required and granted by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC), Victoria Police Research Coordinating Committee, the Justice Human Research Ethics Committee as well as through a letter of support from Corrections Victoria supporting participation of their workforce in the research. In addition, approval was required from the Department of Education and Training. In line with the ethical approval all participants received and explanatory statement and signed a consent form prior to interview or focus groups. Ethics require that participant identities remain confidential. As a result, no potentially identifying information is included in this Report. Engagement with victim/survivors required high risk ethics approval. Such approval dictates careful attention to the needs of victim/survivors. Ethics approval and ethical engagement with these participants means that the interviewee is required to have a high level of demonstrated integrity, skill and expertise in conducting this type of interview. While the topic - family violence information sharing - is set out in the explanatory statement and restated by the interviewer, beyond the initial introduction and explanation the shape and content of the interview is primarily determined by the victim/survivor. In such interviews, the interviewer does not push for additional detail or information but is guided by the interviewee as to what she is comfortable in discussing/sharing.

Timelines

The Review took place from October 2017 to May 2020 when this Report was finalised.

The Table below sets out the overall timeline of the review, outlining the blocks of time spent on each component – planning, ethics approval, data collection, analysis and reporting.

Table 6: Evaluation timeline

|

Activity |

Description |

Time frame |

|

Establishment Phase |

Contract negotiated signed. Kick off meeting. |

October/November 2017 |

|

Project Plan and Evaluation Framework developed and finalised. |

Developed by Monash and amended on the basis of feedback from FSV |

October/November 2017 |

|

Document Review |

|

Throughout the duration of the Review. |

|

Literature Review |

Review relevant international and national academic and policy literature |

April 2018 and ongoing for the duration of the Review |

|

Ethical approval process |

Initial Tranche Low Risk MUHREC approval for survey (plus interviews and focus groups with stakeholders and experts)

High-risk MUHREC approval for interviews and focus groups with victim/survivors and perpetrators

Victoria Police Research Coordination Committee approval to include its workforce in Review research

Corrections Support to include its workforces in Review research

JHREC approval to include its workforces in Review Research |

October 2017/January 2018

|

|

|

Phase One CVRC support to include additional workforces in Review

Youth Justice support to include its workforce in the Review

Department of Education and Training support to include its workforces in the Review

JHREC ethics amendment for Phase One workforces |

April/June 2018 |

|

Surveys |

Initial Tranche Baseline survey (Survey One) distributed prior to the commencement of the FVISS. |

Survey One 30 November 2017/26 February 2018. |

|

|

Phase One Baseline survey (Survey One) distributed prior to the commencement of FVISS to these organisations and services.

|

Survey One 16 August / 26 October 2018

|

|

|

Initial Tranche and Phase One Survey two includes a number of the same questions to Survey One for purposes of comparison. Additional questions focused on the FVISS. |

Survey Two 29 July 2019 /Tuesday 1 October 2019 |

|

Analysis of Initial Tranche survey and delivery of Baseline report |

Baseline Report drafted and finalised with FSV feedback. |

March/April 2018 |

|

Interviews with experts and managers. |

First period of data collection (Initial Tranche) 14 experts 20 managers

16 Service Providers

Second period of data collection (Phase one) 21 experts 30 managers |

Experts

Managers Service Providers Interviews February/April 2018

Experts Managers |

|

Focus Groups with ISE workers |

First period of data collection (Initial Tranche) 11 focus groups conducted with 95 participants. |

April/May 2018 |

|

|

Second period of data collection (Phase One) 8 focus groups conducted with 60 participants |

August/October 2019 |

|

Training Observation

|

Review team members (x2) observe Information Sharing Scheme Manager training |

May 2018 |

|

|

Review team members (x2) observe two day FSV/DET MARAM/FVISS/CISS training |

December 2018 |

|

Analysis of training evaluation forms data |

Quantitative and qualitative analysis of data from Initial Tranche training participants’ evaluations of FVISS training (delivered between 15 January to 28 February 2018) |

May 2018 |

|

Analysis and report drafting |

Analysis of Survey One and drafting and finalising Baseline Report |

March/ April 2018 |

|

|

Analysis of first period of data collection, documents, drafting and finalising of Interim Report |

May/June 2018 |

|

|

Drafting and finalising Updated Evaluation framework |

September/October 2018

|

|

|

Drafting Survey Two |

September 2019 |

|

|

Analysis of second period of data collection, all surveys and documents and drafting and completion of Final Report |

December 2019/ May 2020 |

|

Victim/survivor interviews and Focus Groups |

First period of data collection (Initial Tranche) 8 interview participants; 18 participants total Initial Tranche |

May/November 2018 |

|

|

Second period of data collection (Phase One) 1 interview participant; 8 participants total second phase 26 victim/survivor participants total |

November 2019 |

Limitations

All research methods have limitations. One limitation is that those who participated in the Review may be generally more engaged with family violence reforms and more supportive of the reforms than those who chose not to participate. It is clear from the Report that those who participated were committed to information sharing principles, critically engaged and willing to provide suggestions for improvement of the implementation of the Scheme and reflect on any unintended or adverse consequences.

The Review was designed to consider the implementation of the FVISS and its outcomes. The outcomes of the FVISS, including outcomes in terms of the goals of the Scheme, have been challenging to capture or quantify. First, the Scheme is still a relatively new one, so processes are still being put in place and direct validated outcomes are difficult to discern. Second, multiple reforms are taking place simultaneously so it is difficult to isolate the benefits of any one reform on victim/survivor safety (see, for example, Regulatory Impact Statement 2020: 11). This whole of government reform means participants often made reference to matters that are not directly relevant to this Review or to the work or activity of FSV. Where data emerged that was linked to the implementation of the FVISS, i.e. such as incorrect assumptions about the implications or extent of an aspect of the FVISS, it has been included as it is germane to Review questions of effectiveness and intention. Third, participants in the Review typically did not know with any degree of certainty what impact sharing family violence risk information had on victim/survivor safety in any particular case. Finally, on an aggregate, systems wide level there is no single measure, or composite of measures that can be used to confidently track any trends in victim/survivor safety or perpetrator accountability. Throughout the Report, however, we have used examples, case studies and pertinent stakeholder feedback reflecting on outcomes wherever possible.

The use of a baseline survey with the Initial Tranche and Phase One was designed to capture change overtime. There are significant limitations to the degree the survey was able to achieve this. The baseline survey included a ‘panel’ component where respondents identified themselves as willing to take part in a subsequent survey. This approach potentially allowed for the matching of responses to individuals over time in ways that would allow direct comparison of responses. However, there were too few matching responses in Survey Two to allow for this, i.e. not enough people who identified themselves in Survey One as willing to take part in Survey Two actually took part in the Survey Two. In addition, Survey Two had significantly fewer respondents than Survey One and the spread of respondents was different. These factors limit the interpretation of change as statistically significant. It is likely a more robust measure of change in practice could take place across a longer period, as sharing practice will be more fully embedded.

The use of focus group methods where many voices speak means direct attribution of quotes to any particular participant is not possible. This limitation however is also a safeguard of participant confidentiality. Of the practitioners included in the Initial Tranche and Phase One, only a proportion participated in the research, although agreed participation targets were met. While there was a broad spectrum of Initial Tranche and Phase One ISE categories included in the data collection they were not a ‘representative sample’ of the Initial Tranche or Phase One ISE categories. This means that the proportion of participants from each category of ISE included in the research does not match the proportion of workers from each ISE category. This is a common research limitation. Regardless, the stakeholder engagement, including victim/survivors, mixed methods approach including the analysis of a wide range of relevant documents and the literature review provides a robust foundation for the analysis and recommendations.

Approach to representing and reporting the data

We have taken the following approach to the data in the Report:

- The sources of data, surveys, focus groups, and interviews are integrated in the examination of each theme and question. Each different source of data has been triangulated to validate or strengthen a theme or finding.

- Consistent with the above where quotes are used in the findings sections they are used to reflect key data findings.

- Where, as is often the case, contradictory or diverse perspectives and experiences are evident this is made clear in order to capture the nuance of opinion. Some participant misunderstandings are included and noted as they provide important insights on the efficacy of implementation and on communication processes.

- The Report uses quotes exclusively from the second period of data collection, with the exception of the women’s voices.

- Throughout the Report there is attention to the temporal aspects of implementation, so that we contrast the themes and issues from the first period of data collection to the second period to identify continuities and discontinuities in these between the earlier and latter stages of implementation.

- In line with an ethical approach to research we have not identified stakeholders beyond broad generic categories and have removed any identifying information from quotes and in the discussion.

- Case studies and examples from relevant datasets are used wherever appropriate to exemplify themes and to reflect on outcomes.

- The experiences and perspectives of victim/survivors are considered critical to the Review. To reflect this these are located at the beginning of the findings section.

- The position of First Nations people in relation to the collection of government data is unique. The continuing history of colonisation and colonial relations of power make it difficult for First Nations voices to be heard. We have attempted to amplify these voices by providing them directly after the victim/survivors’ perspectives, which also include First Nations women.

Updated